The connection between intermediate hosts or vectors and infection with parasitic diseases is not intuitive. Indeed, the method by which humans and their livestock become infected with parasites was unknown for most of human history.

Malaria, for instance, was thought to be contracted by breathing in bad air, hence the name mal aria, derived from Medieval Italian. It was only in 1897 that Sir Ronald Ross made the link between malaria transmission and a particular species of mosquito. Indeed, the hypothesis that mosquitoes might transmit a parasite from one person to another when blood feeding had only been formulated a few years earlier by Sir Patrick Manson.

Because the link between biting insects and parasitic infection is not obvious it is not surprising that communities living in areas endemic for vector-transmitted diseases do not always understand how infection occurs. Yet this knowledge is vital if communities are to be engaged in programmes of vector control.

One such infection is onchocerciasis. Commonly known as river blindness, it is transmitted by black flies.

Onchocerciasis

Symptoms of onchocerciases include intense itching of the skin, loss of skin elasticity and pigmentation, and eventually, blindness or epilepsy can occur.

These symptoms are caused by hundreds of larvae (microfilariae) of the parasitic round worm Onchocerca volvulus, which are released each day by adults that live coiled in nodules under the skin.

Microfilariae migrate to the skin during the day where they can be ingested by biting black flies. The disease is prevalent in much of Sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Brazil, Venezuela and Yemen.

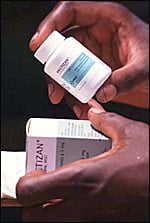

Ivermectin, relieves symptoms by temporarily stopping the production of larvae. However, the effects are not long-lasting and adults are not killed, so oral doses are needed each year.

Black flies

Black flies of the genus Simulium are biting flies that lay their eggs on vegetation or stones in fast flowing streams and rivers. When feeding on an infected person, microfilariae present in the skin are ingested. These develop in the thoracic muscles then move to the head ready to be transmitted during the fly’s next blood meal.

Control Programmes

Between 1974 and 2002 control measures were implemented in Africa by the Onchocerciasis Control Programme and targeted the black fly vector by aerial insecticide-spraying directed at black fly habitats along the edge of rivers. However, by 2002 this strategy had changed and the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, which began in 1995, focussed, not on vector control, but the disease-causing microfilariae via community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI).

The Mban valley

In 1998 the CDTI programme was started in the Mban valley, in the Central region of Cameroon, where the prevalence of onchocerciasis was amongst the highest in the country. However, after 20 years of CDTI implementation, microfilarodermia prevalence was still over 50% in some communities.

The Mban valley has very high densities of black flies along the banks of the Mban River. An entomological survey, conducted in 2015/16, reported remarkable annual black fly-biting rates of 606,370 bites per person and an annual transmission potential of 4,488 larvae per person, yet no vector control was being carried out.

Even though ivermectin treatment will clear circulating microfilariae, reinfection is inevitable whilst black fly populations continue at this density.

A black fly control project, based on community involvement, is thus proposed. The success of this is likely to depend upon community understanding and commitment. Therefore, a team from the Centre for Research on Filariasis and Other Tropical Diseases, Yaoundé, Cameroon conducted a survey to understand how much members of the local population understood about onchocerciasis and black fly bio-ecology.

The survey

Two villages that are located close to the Mban River were selected for the study. Inhabitants over 15 years of age were interviewed individually and the responses recorded on a questionnaire. The local terms for onchocerciasis and black flies, “manonomanbou” and “mbou” respectively, were used to ensure understanding and the participants were divided into two categories depending upon their occupation, and thus exposure to black flies. The majority of the 215 individuals in the sample were farmers, fishermen or mined sand and would thus have high exposure to black flies.

Knowledge of onchocerciasis and black flies

Over 80% of the participants had heard of onchocerciasis, most knew about ivermectin and only 10% said they did not take it. However, knowledge of the role of black flies was scarce.

Although almost everyone had heard of black flies and most thought they could transmit disease, there was considerable confusion about which disease, and only 23% knew that they transmit onchocerciasis.

In terms of their experience of being bitten, most reported a reaction to black fly bites such as itching, scratching, rashes or swelling, and over half of the participants had stopped working because of bites at some time. Almost 80% of participants protected themselves by wearing clothes over all of their body.

The oldest people, and longest residents, in the villages knew most about onchocerciasis and its transmission and those who had not heard of the disease had spent less than 10 years in the locality.

In terms of black fly ecology, the rainy season was recognised as the peak period for abundance. This is when most farming activities occur and the likelihood of being bitten increases. However, only about 10% knew black flies lay their eggs in the river, and almost half thought they laid eggs on a common forest tree that is actually attacked by gall insects that could be confused with black flies.

Overall, it was clear that there was understanding of aspects of onchocerciasis that directly affected the village residents; namely, the disease, and also recognition of the biting nuisance of black flies, but the link between the two was rarely made. This lack of understanding may explain, or be caused by, the sole focus of control measures on disease treatment for the last 20 years. The authors suggest there may be fatigue and a lack of motivation during the training of the volunteers executing mass drug administration, which could cause a failure of the spread of knowledge.

The future

This study emphasises the importance of teaching the link between a parasitic infection and the vector that spreads it. Awareness of black fly biting nuisance and subsequent loss of working time, in combination with new knowledge of the role they play in causing onchocerciasis, is likely to enhance the success of community based black fly control programmes in the future.

Since writing this blog a new article about Onchocerca in the Mban valley has been published in Parasites and Vectors

Comments