Arboviral diseases are caused by a group of viruses spread to humans by arthropods such as mosquitoes or ticks. Arboviruses can be harboured and amplified by wild birds and some animals. Once a bird or animal is heavily infected with virus particles, a vector feeding on it may become infected, passing the virus to a human when the infected mosquito bites.

The most prevalent worldwide arboviral diseases are dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, and West Nile fever. However, there are many more, such as two encephalitis-causing viral diseases endemic to Australia: Kunjin, caused by a strain of West Nile virus, and Murray Valley encephalitis (MVEV). These latter two generally cause only mild illness, though a few people have become very sick and some have died.

In early 2022, 4 patients treated in the city of Albury, New South Wales (NSW), Australia, presented with symptoms indicative of encephalitis. Tests did not reveal any underlying causes, including the endemic Kunjin and MVEV. They remained undiagnosed until a report of the occurrence of Japanese encephalitis virus in pigs in Victoria, NSW and Queensland was circulated. This was the first report of this virus in mainland Australia. The area around Albury contained many piggeries and, to the physicians’ surprise, all four human blood samples proved positive for Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV).

Focusing on one of the survivors, Jack McCann, this story is told by Meredith Wadman in her article Rude Awakening.

Japanese encephalitis virus

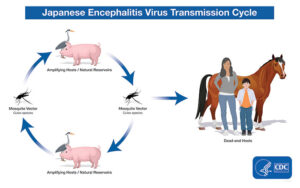

JEV is the most important cause of viral encephalitis in Asia. It is a mosquito-borne flavivirus, and belongs to the same genus as dengue, yellow fever, and West Nile viruses. It occurs particularly in rural agricultural areas, often associated with rice production and flooding irrigation. In Asia, JEV is transmitted through the bite of infected Culex species mosquitoes, particularly Culex tritaeniorhynchus. The usual hosts are wading birds and pigs. Viral concentrations in the blood of humans are not high enough to infect feeding mosquitoes.

In humans, most JEV infections are mild or without apparent symptoms, but approximately 1 in 250 infections results in severe clinical illness when the virus enters the brain. These symptoms include high fever, seizures and coma, and case-fatality rates can be as high as 30%, with survivors suffering from severe cognitive impairment. In pigs, JEV causes stillbirths and mumification of foetuses.

The source of the Australian outbreak

Altogether 45 people were sick and 6 people died of JE in this Australian outbreak. The main source of the virus is assumed to be pigs or waterfowl or both, but where did the infection originally come from?

Although JE had not been recorded on the mainland, a few cases had previously been reported on Australian tropical islands. This included one island, 2,500 km north of the 2022 outbreak, where the virus had the same rare genotype as the one detected in NSW.

There had been a huge increase in the population of waterfowl in the area, including several species of egret and a heron, and all known to be capable of harbouring JEV. This increase is connected to record-breaking rains that followed a 3-year drought and caused flooding and the massive expansion of wetland habitats. Some experts suggest infected migrating birds may have arrived on the Northern coast of Australia a couple of years previously and moved into NSW following their habitat expansion.

In conjunction with the wetland expansion, populations of the mosquito Culex annulirostris, known to be a vector of JEV, also occurred.

Early 2022 saw the detection of JEV infections in 80 piggeries, mainly in NSW. No cases were detected in workers on the pig farms, however, the JE patients lived within mosquito flying distance from them.

It seems highly likely that the original source of the JE infections arrived via migrating wildfowl. Mosquitoes biting these infected birds then passed the virus to pigs where the virus was amplified. Alternatively, swarms of infected mosquitoes could have been swept south from the northern coast of Australia by a cyclone and started infections in birds and pigs.

What is not clear is whether the human infections resulted from bites from mosquitoes that had become infected by biting birds or by biting pigs.

What happened next?

The Australian government responded swiftly by issuing anti-mosquito measures and distributing 125,000 vaccine doses to vulnerable communities. The outbreak was officially over by June, but researchers recognise the virus may still be present and amplifying in Australian piggeries and emphasise the importance of early detection of future disease outbreaks. Genomic analysis of samples from trapped birds and mosquitoes is ongoing, though no samples were positive in the 2023 summer season.

Samples from piggeries in Western Australia also tested positive for the virus, suggesting the virus was widespread, and could become endemic. However, although three new cases were detected at the beginning of the 2022 summer season, no more occurred that year and the virus apparently vanished.

It has been suggested that the La Niña–dominated conditions that created the extensive wetlands in NSW in 2022 were exacerbated due to excess moisture in the air resulting from climate change. Another example of how the distribution of infectious diseases could be subject to change and unpredictability in the future.

Comments