While the Ebola outbreak across West Africa only hit the headlines in 2014, when it caused a two-year epidemic, the disease was in fact first discovered in 1976 with outbreaks in Sudan and the DRC. The latter outbreak occurred near the Ebola River towards the northwest of the country, from which the virus takes its name.

Ebola had been an ongoing public health problem across sub-Saharan Africa, claiming 1590 lives between 1976 and 2012. However, its virulence was recognised in 2014 with the start of the two-year epidemic, which began in Guinea and spread across to neighbouring Liberia and Sierra Leonne. Cases were later confirmed in Nigeria and Senegal. The epidemic was officially declared over in June of 2016, after claiming 11,310 lives.

The outbreak response to the West African Ebola virus epidemic involved international agencies of the United Nations such as the World Health Organization and UNICEF, amongst numerous other NGOs. These organisations worked closely alongside in-country Ministries of Health to manage the outbreak. Despite this, the outbreak response has been criticised for a shortage of doctors and lack of community engagement, which led to distrust within communities towards foreign healthcare workers. At the start of the outbreak in 2014, distrust amongst villagers led to the deaths of eight healthcare workers. Villagers suspected that the healthcare workers were responsible for spreading the disease.

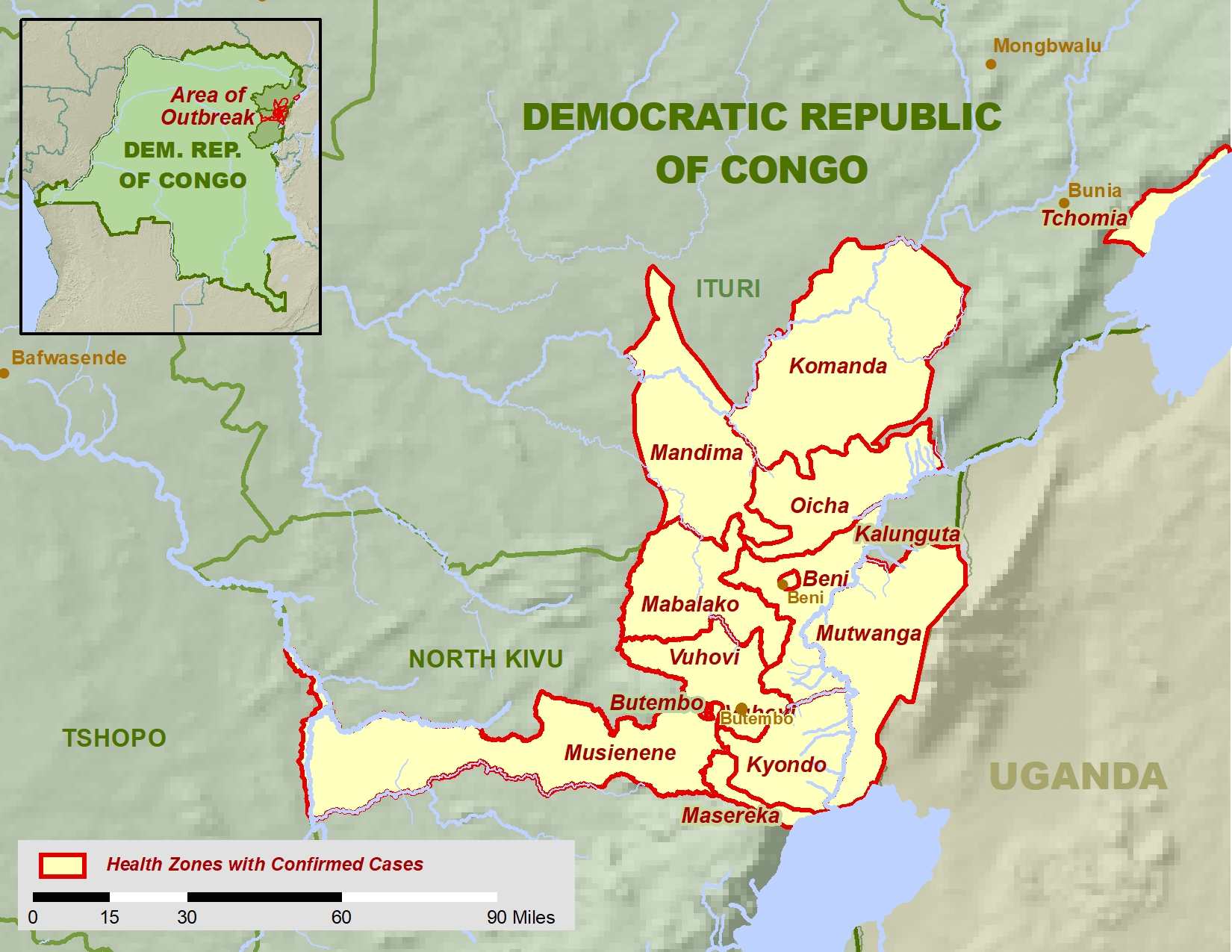

Ebola has once again been in the news with the second largest outbreak starting in the DRC in August of this year claiming ~300 lives so far.

Concern is also rising about the outbreak spreading to neighbouring Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda and South Sudan and Uganda is preparing to vaccinate frontline health workers, as is South Sudan.

What is being done?

Like most diseases, education and behaviour change are key to minimising the transmission of Ebola. This was acknowledged with the establishment of a telephone helpline in Guinea during the 2014 outbreak. The helpline aimed to educate about harmful rumours surrounding Ebola prevention and increase awareness about the importance of hygiene behaviours in preventing the disease. Community outreach and social mobilization also played a crucial part in building trust and educating at-risk communities.

Social mobilization and community engagement involves conveying key messages to individuals, families and key stakeholders within communities. These messages should be delivered both nationally and locally, using different methods. Examples of local methods include recruiting ‘Wise people’, who have trust within the community to disseminate key messages about the disease. National social mobilization has involved television and radio broadcasts.

One health

Ebola is a zoonotic disease, meaning it can be transmitted between humans and animals. Ebola virus disease is caused by a group of six viruses within the Ebolavirus family; four of which can infect humans.

Scientists believe the main reservoir host of Ebola virus to be fruit bats of the Pteropodidae family, which spread the virus to other wildlife such as monkeys and gorillas. Close contact with these animals causes humans to become infected. The disease can then be transmitted between humans through direct contact with infected fluids or surfaces.

The bush meat trade across equatorial African countries, whereby wild animals, including the hosts of Ebola, are caught, killed and sold for meat is thought to be a probable cause of human infection. Therefore, going forward, education has also encompassed both veterinary and public health issues within a ‘One Health’ approach.

Surveillance

Surveillance by case identification is key to outbreak preparedness. During the 2014 Ebola outbreak, the introduction of new mobile laboratories in Liberia improved access to treatment. This also allowed increased passive case detection, thus improving surveillance in hard to reach areas. Resources such as mobile laboratories are very important for quick diagnosis of the disease, reducing the exposure to non-infected patients.

Vaccination

There are several potential candidates for an Ebola vaccine, with experimental vaccine trials ongoing in the DRC. The rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine currently being deployed in the DRC is being used on compassionate grounds, as it is not yet commercially licenced. The vaccine is recommended for use against one strain of the virus, the Zaire ebolavirus, and was found to be safe and protective in several studies across Africa, Europe and the USA.

While this vaccine may be promising, vaccine research faces several hurdles. There is a lack of data on how effective and safe vaccine candidates are on high risk groups, including children, pregnant women and the immunocompromised. Vaccine candidates also need to be safe, and any adverse reactions identified. Finally, as with other Ebola interventions involving foreign health workers there needs to be trust within the community for vaccines to be accepted.

One Comment