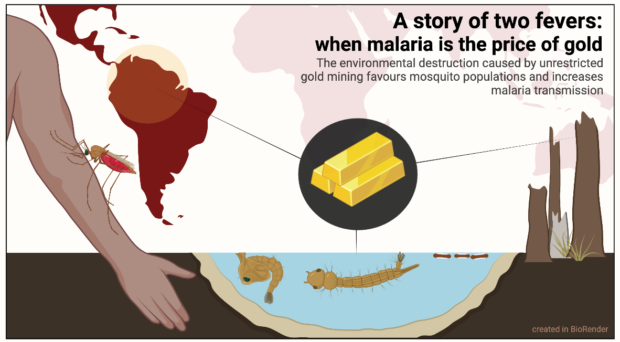

Gold mining, in all its forms, causes untold damage wherever it happens. But illegal mining, which takes place without state permission or regulations, can be especially devastating, and is inextricably linked to poverty and violence in countries like Colombia, Nigeria, and South Africa. And yet, desperate times call for desperate measures. Socioeconomic hardship forces many to seek potentially dangerous work in order to survive – and enter the world of illegal mining. Miners are exposed to a long list of health hazards, handling toxic chemicals, noxious fumes, and in some cases sweltering temperatures underground. Lung diseases and cancer are highly common, and not far behind, is malaria.

Malaria is a life-threatening parasitic disease transmitted by the bite of Anopheles mosquitoes, insects whose first three life stages are aquatic. They thrive in bodies of water like ground pools, irrigation canals, wells, and pits or ditches that fill up when it rains. The environmental destruction created by unrestricted gold mining is responsible for the creation of both temporary and permanent breeding sites, resulting in a local explosion of mosquito populations. Miners are continuously exposed to malaria, and the disease moves with them as they travel between worksites across different regions.

In the mining communities of South America

A recent study in Colombia indicated that between 2012 and 2018, over 44,000 cases of malaria were reported in the country’s mining population. Most cases were reported in men, but many women and children also described mining as their main (or sometimes only) source of income. Despite these case numbers, malaria underreporting is highly suspected since miners lack access to healthcare services due to the ‘informal’ nature of their jobs. Infections are mainly due to Plasmodium vivax and P. falciparum, with many asymptomatic cases further hindering detection and treatment.

In the neighbouring Venezuela, researchers have described how illegal gold mining is one of the main drivers of malaria transmission in the south-eastern part of the country, associated to the severe landscape modifications. Specifically, they found that “abandoned open lagoons or mining dug-outs left after clearing vegetation” were responsible for the creation of new breeding sites, favouring species like An. darlingi and An. albitarsis. The dire socio-economic situation in Venezuela has supported the growth of illegal gold mining activities in areas where disease clusters have also been identified, and the broken health system contributes to the spillover of malaria from these areas to other parts of Venezuela and neighbouring countries.

In Guyana, malaria is mostly concentrated among mining populations, where migrant workers have limited access to health services and remain outside the public health system. The two ‘fevers’ are so tightly linked in this country, that researchers were able to develop a model to forecast malaria trends in Guyana based on the price of gold. This variable appeared to be the driving force behind a rise in malaria cases between 2008 and 2014, when high gold prices increased mining activity and motivated men (anywhere between the ages of 15 and 50) to participate in mining activities.

Heading slightly south, in the Amazon, extensive deforestation and clandestine gold mining camps are increasing malaria incidence in indigenous territories. Unfortunately, the problem remains unaddressed because the health care system has difficulties accessing populations in some of these remote areas. Due to lack of reliable information on malaria, miners often self-medicate, increasing the risk of drug resistance. In the Brazilian state of Roraima, near Venezuela and Guyana, miners commonly witness the death of their co-workers and friends due to malaria. Frequent migration across borders in search of work contributes towards the risk of malaria transmission in the region.

A common problem around the world

And these situations extend to many other countries. In a gold mine in Burkina Faso, up to three quarters of miners and their families can be infected with malaria, their living conditions constantly exposing them to mosquito bites. An artisanal mining district in Ghana reported a high prevalence of malaria in children under 5, and researchers found a significant association between cases and how close these families lived to the mines. In Myanmar, malaria is one of the most common afflictions among miners, together with lung-related illnesses. Furthermore, malaria is not the only vector-borne disease associated to mining. There are also records of increased leishmaniasis risk in French Guiana as miners go into the forests for work.

The link between malaria and gold mining is not new. However, it remains largely overlooked by many public health systems, perhaps due in part to the nature of these disenfranchised populations. Multidisciplinary studies are needed to further understand malaria transmission in mining communities (including their families and other non-mining personnel) to contribute actionable health policies towards disease control.

None of the gold miners will ever see the metal again, many barely making enough to feed their own families. Their lives are the real cost of that gold, and malaria is part of the price they pay.

Comments