Archeoparasitology

Intestinal parasites, such as helminths, have plagued humans for millennia, and in some cases have even co-evolved with us from pre-history. For example, the study of pinworms from humans, as well as the greater and lesser apes, uncovered the parallel evolution of pinworms and primates.

The field of archeoparasitology, or the study of parasites preserved in an archeological context, can help inform scientists of the distribution, prevalence, evolution and origins of parasitic infections worldwide, and can even provide information on the past farming, dietary and sanitation practices of ancient communities.

The first archeoparasitological study, conducted by Marc Ruffer in 1910, discovered calcified eggs of Schistosoma haematobium (the urinary blood fluke) in the kidneys of two 20th dynasty Egyptian mummied individuals from around 1000 BCE! Similarly, whipworm, pinworm and Schistosoma japonicum eggs have been found during the autopsy of a Han-Chinese mummy dating from approximately 200 AD.

Excavation of a 7th century BCE cesspit at Armon Hanatziv, Jerusalem

A recent case study by Dafna Langgut from the Institute of Archaeology and The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University has investigated an excavation site at Armon Hanatziv (southern Jerusalem) for evidence of intestinal parasites.

The excavation, which was started in 2019, unearthed a large and architecturally impressive royal estate surrounded by a garden of fruit trees, a water reservoir and toilet installation that has been dated to the mid-7th century BCE. It’s this toilet installation and the sediments found underneath that have investigated in their study.

Just for some context, this is around the same time that the city of Byzantium (later known as Constantinople and Istanbul) was founded, and when Nebuchadnezzar II became king of Babylon.

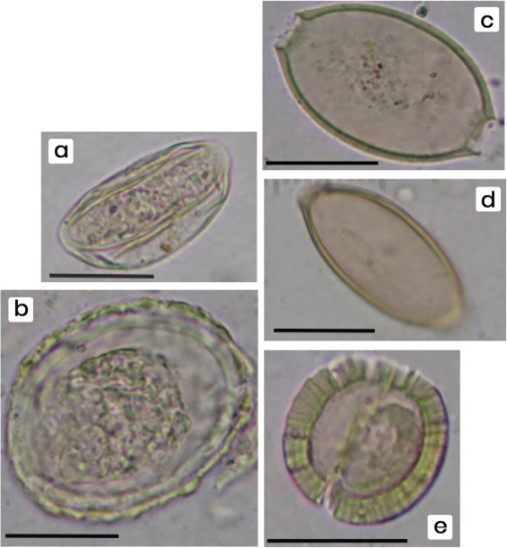

Overall, 15 sediment samples were collected from below and around the cesspit, which were then subjected to several rounds of cleaning via sonication, and subsequently were separated based on sediment density using centrifugation. The floating suspension, containing any parasitic worm eggs, was removed and used for parasitological identification under a light microscope.

Parasite eggs are often extremely durable due to the strong shell surrounding many, enabling them to survive in the environment for weeks to months, however, they can often be detected after many years in some cases.

Findings from the study revealed that six of the sediment samples contained well-preserved eggs belonging to Ascaris lumbricoides (roundworm), Trichuris trichuria (whipworm), Taenia spp. (beef/pork tapeworm), and Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm).

Possible implications for the health of ancient communities in Jerusalem

The presence of roundworm, whipworm and pinworm eggs in the faecal sediment suggest that sanitation and hygiene was poor in 700 BCE Jerusalem, as these parasites are transmitted through ingestion of parasite eggs due to contamination of hands, food and/or water with faeces.

On the other hand, the identification of beef or pork tapeworm eggs indicates that cattle and/or pigs were readily consumed in ancient Jerusalem, as these eggs are transmitted to humans through ingestion or raw or poorly salted, dried, smoked, or cooked pork or beef.

Rather significantly, the identification of parasitic worm eggs at Armon Hanatziv provides the earliest evidence of the parasitic infection of humans in the region of ancient Jerusalem and the Levant, and therefore improves our understanding and sheds light on the history and dispersal of infectious diseases in the ancient world.

The existence of a toilet installation and carved stone seat in the grounds of a lavish estate highlights the high-status of the individuals that made use of the installation. Certainly, the authors note that in ancient Jerusalem a toilet was a symbol of wealth enjoyed by only the richest of society. Despite this, the presence of parasitic worm eggs suggests that even those ‘high-status’ individuals with access to an apparently high level of sanitation could not avoid infection with often debilitating parasitic worms.

Comments