A recent study by Katrin Bisterfeld and colleagues from the University of Veterinary Medicine in Hannover and Justus-Liebig-University in Giessen, have investigated the epidemiology of several cardio-pulmonary (heart and lung) parasitic nematodes circulating in European wildcat (Felis silvestris) populations across Germany.

Prior to 1922, European wildcats were at risk of eradication, but since then strict protections have been put in place in Germany, which saw the wildcat population subsequently rebound and is now listed as Least Concern in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Nonetheless, the health of these wildcat populations must be monitored to ensure their survival, and although not able to infect humans (as far as we’re currently aware), these parasites can be transmitted from wildcats to domesticated cats (Felis catus), and so their increasing numbers might pose a significant health risk to our feline friends.

As such, this study aimed to survey cardio-pulmonary parasites in F. silvestris in Germany to evaluate the prevalence and intensity of infection, assess whether they might play an important role as reservoirs of pathogens for domestic cats, and also bring the surveillance of helminth infections in wild European wildcats in line with other European countries.

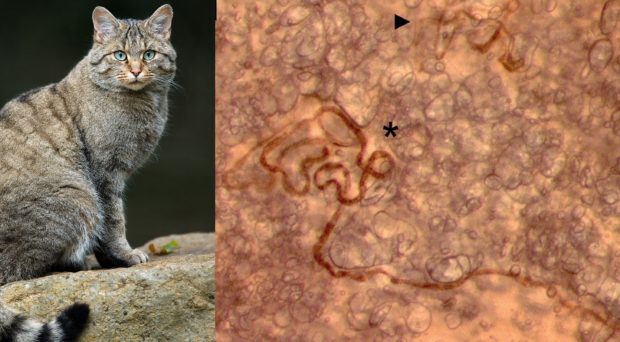

The cardio-pulmonary nematodes; Troglostrongylus brevior, Angiostrongylus chabaudi, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, and Capillaria areophila were focused on as they’re known to be important lungworm parasites of felines (and often other mammals). They have been shown to widely infect wildcats in other European countries, and can cause severe pulmonary lesions and bronchial diseases in their wildcat hosts, as well in domesticated cats.

Parasite life cycles differ between the species, and in the case of A. chabaudi is still largely unknown. Generally, infection of cats occurs through ingestion of parasites from the environment, whether in mollusc or annelid intermediate hosts (such as snails, slugs and earthworms), paratenic hosts (such as rodents, birds or amphibians), or directly from the environment.

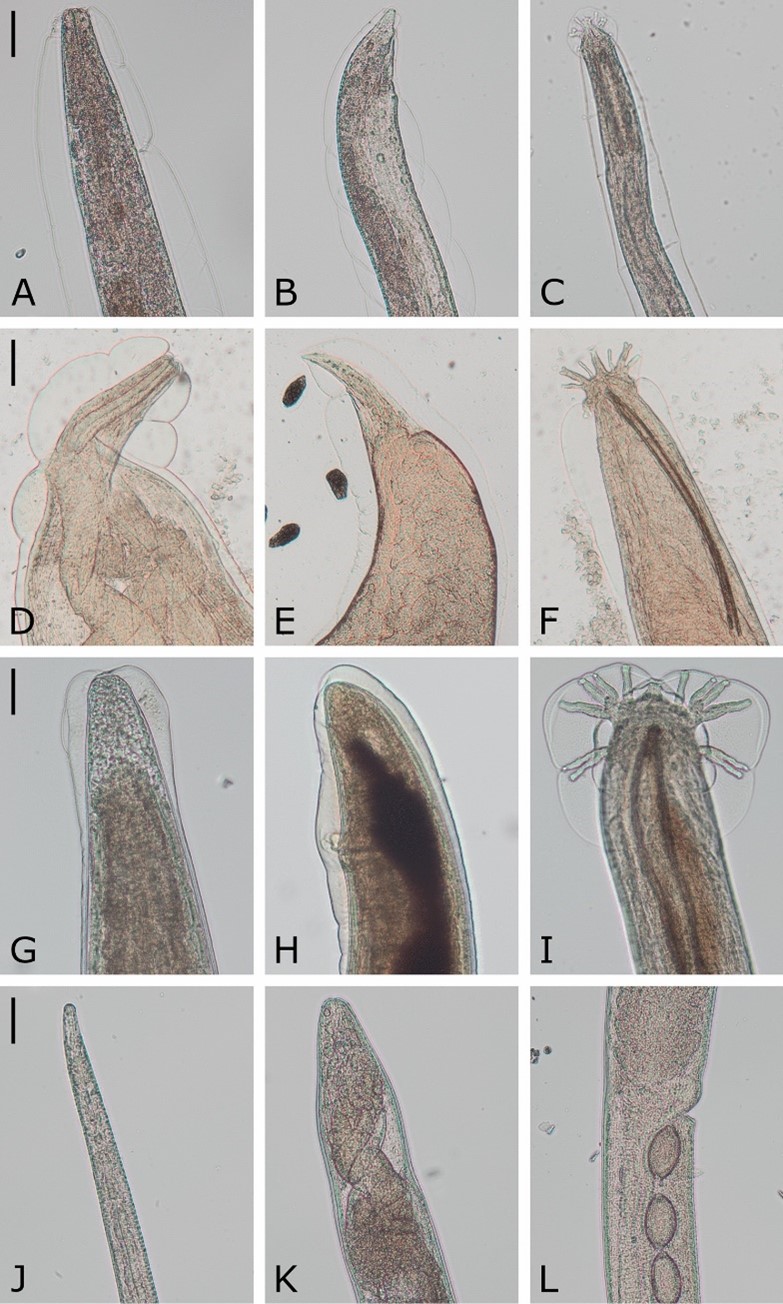

Sampling European wildcats and identification of cardio-pulmonary parasites

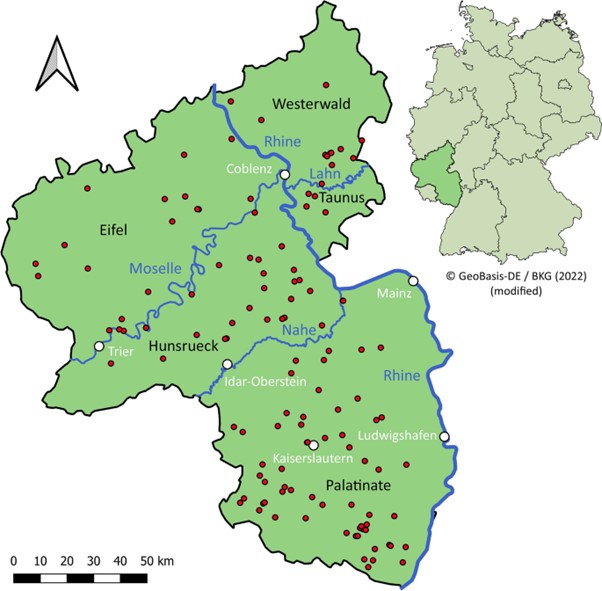

The researchers identified the carcasses of 128 wildcats found in the Rhineland-Palatinate in Southwestern Germany, and dissected them to identify the four parasitic worms. The wildcats were identified morphologically, and parameters such as sex, age, nutritional content, and decomposition-level were collected.

The hearts, lungs and surrounding tissues and vessels of the wildcats were dissected, with identified parasites undergoing both morphological and molecular species determination.

Prevalence of each parasite species, infection intensity, and coinfection prevalence

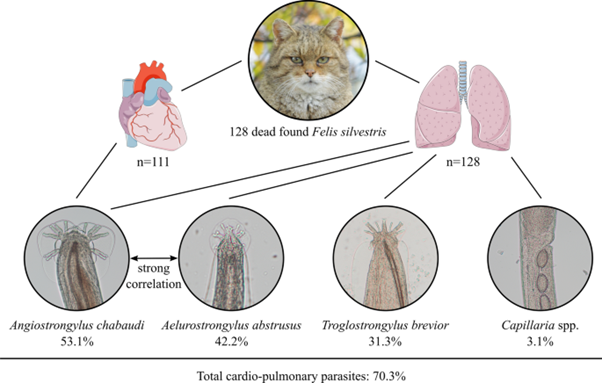

Of the sampled wildcats, 70.3% (90/128) were found to contain at least 1 cardio-pulmonary parasite species, confirming previous reports of high parasite prevalence from smaller-scale studies in German wildcat populations. The most frequently detected species was A. chabaudi (53.1%), followed by A. abstrusus (42.2%) and T. brevior (31.3%). Capillaria species were rare in comparison (3.1%).

Compared to similar studies conducted in other European countries, T. brevior prevalence was higher than expected given that the parasite is thought to be more abundant in Southern European countries. It is speculated the high prevalence detected may be due to the increasing numbers and distribution of its wildcat hosts, or climate change-related factors. In contrast, the prevalence of Capillaria species was much lower than observed in other German states, as well as in other European countries.

Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and A. chabaudi were found to be similarly prevalent as in other surveyed European countries. As A. chabaudi was commonly detected and relatively little is known of the parasite, further research into the biology of A. chabaudi in wild- and domesticated cats should be conducted.

Within the infected wildcats, intensity of infection ranged from 1 of each parasite species, to 167 A. abstrusus parasites in one sampled wildcat. Generally, infections were mild, with wildcats only containing a few parasites.

Coinfections were, however, found in 64.4% of the infected wildcats, where double parasite species coninfections were most common for Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and A. chabaudi (25.6%), and triple species infections for A. abstrusus, A. chabaudi, and T. brevior (16.7%).

In other European countries, coinfections with 2 to 4 different parasite species were found in around 33% of sampled wildcats, demonstrating that on the whole, German wildcat populations experience similar levels of coinfection with cardio-pulmonary parasites as in countries, such as Italy and Romania.

Possible predictors of infection

Generalised linear models (GLMs) were utilised to statistically determine possible predictors of parasite infection, using the parameters mentioned above, as well as the prevalence of coinfections with multiple parasite species.

A significant correlation was found between infection with A. abstrusus and coinfection with A. chabaudi. A significant association was also found between infection status and wildcat age, as has previously been reported for A. abstrusus in domesticated cats.

Interestingly, only a minor connection was found between wildcat nutritional status and infection status, indicating that although cardio-pulmonary parasitic worms are common, they do not seem to seriously impact the overall health of the German wildcat population.

There is, however, a real risk of transmission of these cardio-pulmonary nematodes from wildcat populations to domesticated cats in Germany due to the significant overlap of prey animals between the cat populations, combined with the frequent infection of wildcats with these parasites.

As a result of this likely spillover to domestic cats, the authors suggest that awareness among cat owners and veterinarians in Germany should be a priority, in addition to increasing our understanding of the feline immune response to cardio-pulmonary nematode infections, and improved knowledge on the lifecycle and pathogenicity of the most commonly detected parasite; Angiostrongylus chabaudi.

Comments