The gray wolves of Yellow Stone National Park became locally extinct when the last one was killed in 1926. They were not reintroduced until 1973, following campaigns by biologists and conservationists. The remarkable story of the consequences of their reintroduction and the subsequent recovery of the park ecosystems is well know. In addition to causing a decline in elk and coyote numbers and behaviour, wolves have driven cougars into the more mountainous areas by claiming cougar kills.

These Yellowstone gray wolves have been the subject of a study lasting decades that has yielded data on their population dynamics, behaviour, predator-prey relationships and pathogens.

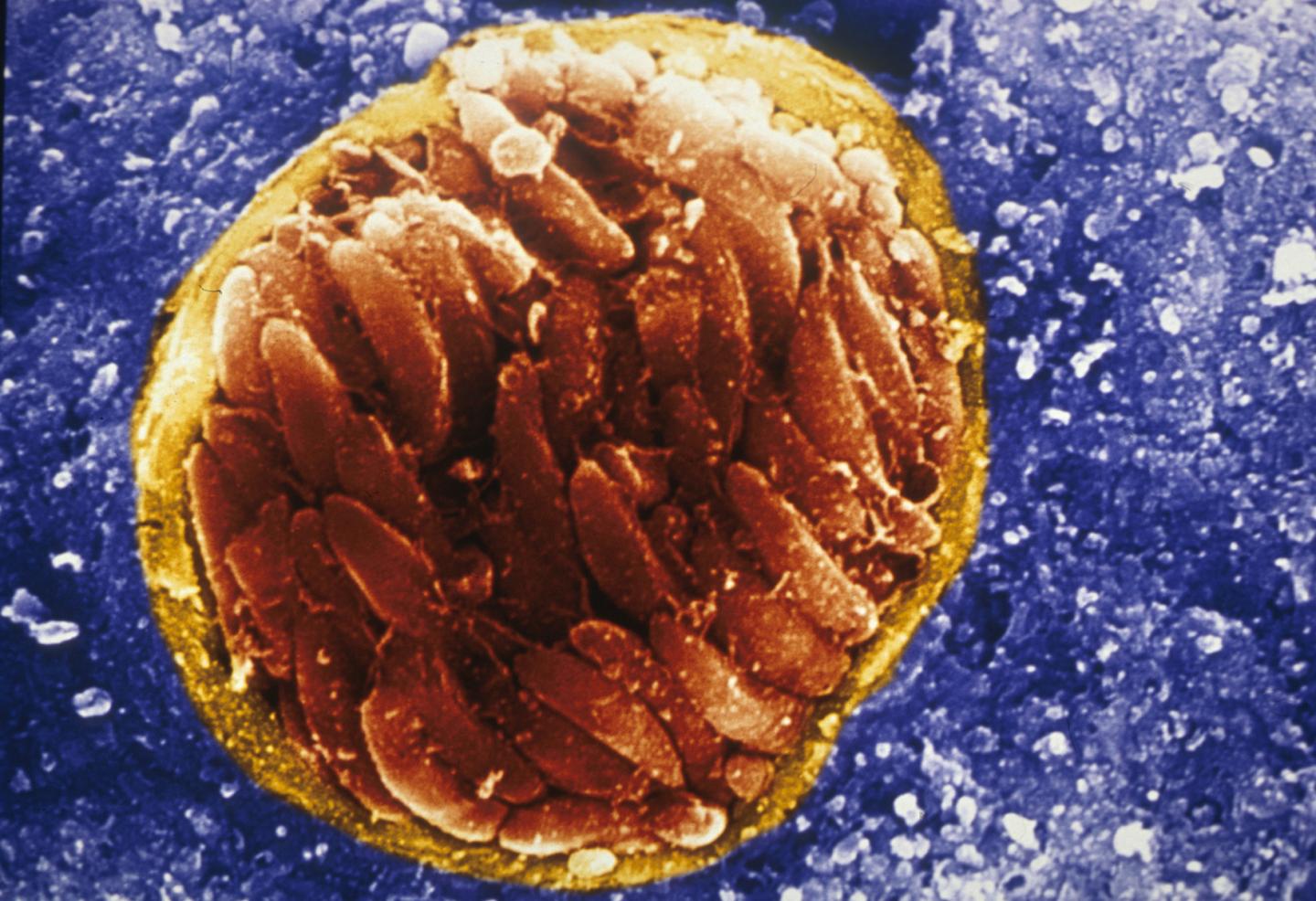

One of the pathogens detected by serological studies of wolf packs across North America is the unicellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii.

Toxoplasma gondii

This parasite has a worldwide distribution and can infect almost all endothermic animals, although only felids can act as definitive hosts (the host where sexual reproduction occurs). Transmission to intermediate hosts occurs via predation of an infected felid or accidental ingestion of oocysts that have been shed in the cat’s faeces and contaminated the soil or vegetation.

Following ingestion by the intermediate host, the parasite multiplies in the cells of the intestinal lining then moves via the blood stream to encyst in the tissues, including the brain.

Several of our past blogs have covered aspects of Toxoplasma’s biology and intermediate-host behavioural changes. Many studies have focussed of its effect on the behaviour of humans, but there is evidence that suggests similar behavioural changes also occur in the intermediate hosts of Toxoplasma when lifecycles occur in the wild, for example when lions and hyenas interact.

The wolves in Yellowstone National Park interact with cougars. Could they be the source of infection and does infection with T. gondii change the behaviour of the wolves? Taking advantage of 26 years of serological and observational data, researchers at the Yellowstone Wolf Project have investigated if and how T. gondii infection in wolves is influenced by their spatial overlap with the Park’s cats, the cougars.

Infection prevalence

They first looked for Toxoplasma infection in the potential definitive host, using data from two sampling periods of 5 and 4 years that were separated by a 12-year gap. T. gondii infection in cougars rose from just over 50% in the first period to a remarkable 73% in 2016-2020.

The infection was not detected in wolves prior to 1999, with the first seropositive sample found in 2000. Thereafter, four- or 5-year sampling periods yielded an increase from 24.5% seropositive to 36.5% by the period up to 2020.

Variables affecting infection

To determine whether the presence of cougars affected the likelihood of wolf packs in these areas being seropositive, the researchers divided the Park into low, medium, and high areas with respect to cougar density. Areas of high density were located in the north of Yellowstone National Park. Wolf seropositivity did indeed increase with cougar density. The likelihood of wolves testing positive for T. gondii infection increased as pack territories were located in areas of low to medium to high cougar density.

Wolf sex had no significant influence upon infection status, but more older wolves were infected than pups, yearlings, or adults under 6 years, possibly because age increased the chance of encountering the parasite. Neither coat colour (black or gray) nor social status (subordinates or leaders) affected infection prevalence.

Parasite associated behavioural changes

T. gondii infection is associated with increased risk-taking and aggressive behaviour. Three aspects of wolf behaviour were monitored in conjunction with T. gondii infection:

- whether an individual wolf moved away from the pack (dispersal)

- whether an infected wolf became a pack leader

- cause of death

The researchers found male wolves dispersed from their pack more than females but, in both sexes, wolves that were seropositive dispersed much more quickly than seronegative ones.

The chance of a seropositive wolf becoming a pack leader was more than 46 times higher than a seronegative wolf and this effect increased with time. This possibly reflects the increased aggressiveness and assertiveness required to become leader of a pack.

There was no difference in the cause of mortality between Toxoplasma-infected and uninfected wolves, whether death was human-caused, wolf-caused, or due to any other known cause.

Conclusions

The likelihood that wolf infections were caused by predation of other infected intermediate hosts, such as elk (their main food source), was dismissed as highly unlikely because only 3.5% of elk in Yellowstone were seropositive for Toxoplasma. The finger definitely pointed at contact with cougars as the source of infection because an increase in the number of T. gondii-infected wolves only occurred in packs whose territory was in the Northern areas of Yellowstone National Park, and in areas overlapping terrain where cougars were at the highest density. Cougar territory was a major ecological predictor of infection.

The increase in risk-taking and aggressive behaviour exhibited by infected wolves is in line with other studies of host behavioural changes associated with this parasite.

Dispersal could lead to higher wolf mortality than living with the pack but offers opportunities for exploiting new territories and experiencing more sexual encounters. Likewise, aggression leading to pack dominance will provide the advantage of greater reproductive success and thus act as an evolutionary advantage.

Previous studies have shown that T. gondii infected intermediate hosts react positively to the scent of felids, potentially exposing them to the danger of being predated and thus passing on the parasite to a definitive host. The authors of this study hypothesise that an infected pack leader may respond positively to the presence of cougars, leading the rest of the pack into contact with T. gondii oocysts. This would create a positive feed-back loop that increases pack infection.

Although this positive feed-back loop could eventually lead to an increase in the range occupied by wolves, and may increase reproductive success, T. gondii infection poses a threat to pregnant wolves as acute infection at this time can lead to litter mortality. Clearly a balance must exist between these advantages and disadvantages for host population dynamics and for the parasite life cycle to continue.

This study is a rare and interesting example of the details of Toxoplasma occurring in the wild.

Comments