Tuesday 11th November marks Armistice day (also known as Remembrance Day or Poppy Day in the UK), the day in 1918 when on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month an armistice was signed between the Allied Forces and Germany that resulted in a ceasefire on the western front and marked the beginning of the end of World War I. The day is used to commemorate members of the armed forces that have died in the line of duty, with services and memorials held in locations in many countries across the world.

While many people were lost to physical injury as a result of the conflict, many others had to endure disease and parasitism as a result of the poor living conditions in the trenches. At Bugbitten we thought the 11th November might be an appropriate time to highlight some of the parasites and pathogens that were prevalent in the trenches during World War I.

“Trench fever”, as the name suggests was a disease that was prevalent in the trenches in World War I. It was first reported from troops in Flanders in 1915 when individuals suffered from the sudden onset of a febrile illness that relapsed in 5 day cycles. At the time the aetiological agent responsible for the disease was unknown.

Although not a severe illness, an estimated 380,000-520,000 members of the British Army were affected between 1915 and 1918. This had obvious implications for the strength of the fighting force due to the large numbers of men that were incapacitated due to the illness. Consequently, much research was carried out to identify the causative agent and the mechanism of transmission of the disease.

Due to the similarity of the Trench fever to Malaria, with its relapsing bouts, it was postulated that the agent could be transmitted by some of the insects found it the trenches and likely by the human body louse, Pediculus humanus humanus, as the disease was prevalent in the winter when other vectors, such as flies, were not.

Transmission experiments conducted by both American and British led groups concluded that the human body louse was indeed a vector of the disease via infectious bite,s but that a more common route of transmission was the inoculation of louse excreta into the body through broken skin.

Attempts to find a treatment for the disease were unsuccessful and prevention focussed on “delousing” of clothes via insecticides. At the time the causative agent was identified and grouped with the Rickettsia and named “Rickettsia quintana” and after the war 6000 men in Britain still attributed their disability as a result of the war to Trench Fever.

We now know that R. quintana would subsequently join the genus Bartonella (along with B. bacilliformis, the agent of Carrion’s disease transmitted by sandlfies).

The genus has expanded rapidly since the 1990s and Bartonella are considered an emerging group of pathogens consisting of over 30 taxa (and many new candidate species) which have been implicated in a wide range of clinical syndromes of humans including Cat Scratch Disease and endocarditis.

They infect a wide range of mammalian hosts and are transmitted by a variety of blood sucking arthropods across the world. Trench Fever is not strictly a disease of the trenches, cases still occur in today but most commonly in the homeless population.

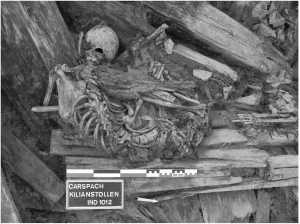

A recent paleoparasitology study published in PLOS ONE found that range of Soldiers in World War I not only contracted vector-borne diseases but also suffered from intestinal parasites. “Kilianstollen” was a German underground bunker located in the Alsace region in France constructed during the Winter of 1915/1916. On 18th March 1918, 34 German

infantry soldiers sought refuge from heavy French shelling in the gallery when it collapsed on top of them and 21 soldiers were killed. The gallery was subsequently excavated in 2011 and the 21 bodies recovered, 3 of these were assessed for infection with intestinal parasites.

Sediment samples from the abdominal cavity of the soldiers were rehydrated, sieved and examined for the presence of intestinal helminth eggs. Two of the 3, a 20 year old soldier and a 35 year old sergeant, were infected with a range of helminths including Ascaris, Trichuris, Capillaria and Taenia spp.

The authors suggested the presence of Ascaris, Trichuris and Taenia were likely due to a range of factors associated with war including bad hygiene and the poor management of waste and poor food preparation.

Capillaria infections are less common in humans but may have been the result of transfer from rats that were abundant in the trenches and were occasionally eaten. Given that 2 of the 3 examined were infected and with a diversity of parasites it is likely that intestinal infection may have been common among soldiers during World War I.

Aside from the injury and suffering caused directly by the war itself, the poor living conditions obviously led to a range of other conditions affecting the health of soldiers in the trenches and the information presented above probably only presents a snapshot of the range of conditions that the soldiers would have had to endure.

Wars can only cause diseases and deaths. Stop wars, please! I hate violence. My city was a paradise when I was a child, it was very safe, I remember when I was to these idyllic beaches, without fear, only peace… I remember that sometimes I ate mango directly of the tree, I used to take baths with a hose, at the house path, without fear… We DONT had violence at these times! It was a paradise. Now, it’s turning a hell (pardon), because the violence is constant. I have fear to leave home. Violence and wars can only cause diseases and death.

Dr AT Kannan Professor Public Health, Kannur Medical College, Kerala

It is well documented that British indian troops had lot of Morbidity due to malaria in the Burmese segments resulting in high case fatalities with API going upto 15