Thinking about how animals mate, one might at first think about the way that mammals do it. But what do we know about how other animals reproduce, including those that some might find rather unattractive, like spiders?

Spiders have evolved a unique way of sperm transfer: besides their four pairs of walking legs, male spiders possess an additional pair of smaller, specialized body appendages, the pedipalps (Fig. 1).

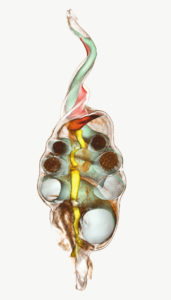

An organ at the tip of the pedipalps of males, the “palpal-organ” or “copulatory bulb” (Fig. 2), is used to take up droplets of seminal fluid from a specially produced sperm web.

The seminal fluid is produced inside the testes, then released onto the sperm web and from there taken up into the palpal-organ for storage until mating. During mating, the male inserts part of its palpal organs into the female genital tract, thereby transferring the seminal fluid into the sperm storage organs of the female.

So far, this might appear quite clear, but how do males control the ejection of seminal fluid inside the female? Very likely, some sort of sensory feedback from the male copulatory organ must be involved.

For a long time, it was considered common knowledge that the palpal organ is free of sensory equipment – deeming it to be a numb structure. This hypothesis was challenged in 2015 when one of our colleagues found a nerve inside the bulb of the Tasmanian Cave Spider (Hickmania troglodytes). Only two years later, these findings were confirmed for a philodromid crab spider (Philodromus cespitum) where similar structures and a potential sensory organ were discovered in the male’s copulatory organ. In the current paper, we explore how common the innervation of the male copulatory organ is in spiders and whether nerves in palpal organs evolved multiple times or can be considered part of the ground pattern of spiders.

To this aim, we conducted a comparative study including key taxa across the spider tree of life. We used a correlative methodological approach including different microscopy techniques (light-microscopy, transmission electron microscopy and X-Ray microscopy) and combined our data in a 3D-model scenario (Fig. 3).

We found nerves in the palpal organs of every spider species we investigated. Innervated palpal organs occur across the spider tree of life, including early diverged taxa such as Tarantulas (Mygalomorphae) and liphistiid spiders (Mesothelae). Our study demonstrates that innervated copulatory organs are part of the ground pattern of spiders. Our findings shed new light on the specific mechanisms of uptake and release of sperm from the male copulatory bulb and change our view on spider reproductive biology in general.

Tim M Dederichs

Latest posts by Tim M Dederichs (see all)

- From spider males and their allegedly numb genitalia - 9th December 2019

Comments