February 7th 2017 4:30 am – It’s a typical Glaswegian morning, the heavens have opened and rain pours down to earth as three researchers from the University of Glasgow throw their kit bags into the taxi and head to the airport for a much sunnier location, Uganda! The adventure begins.

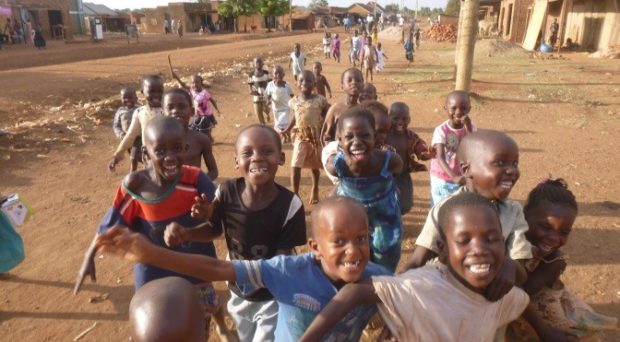

Having rested and met the field team from the Vector Control Division, Ugandan Ministry of Health, we set out to the district of Mayuge, to be our base camp and home for the next month. From here we would drive out daily to the village of Bugoto on the northern shoreline of Lake Victoria to carry out our research on schistosomiasis. Our first aim was to speak to the villagers, with the help of some local health workers, to recruit them into the study and also collect vital survey and mapping information for our research. The children in particular seemed very excited by our arrival and the villagers were very welcoming as word spread quickly about our work.

In Bugoto schistosomiasis is caused by the endemic intestinal trematode Schistosoma mansoni. The parasite undergoes a complex lifecycle. After eggs are excreted in human faeces they hatch into miracidia in freshwater which then infect intermediate snail hosts. Hundreds of thousands of cercariae are then released from the snails into the lake that go on to penetrate the skin of humans who enter this infected water. Within the human host, adult worms develop in the mesenteric veins of the intestine where male and female worms mate. Eggs are produced and the life cycle repeats again. The disease causes much morbidity, reducing growth and cognitive development, and often results in a severe chronic disease as hundreds of eggs lodge in vital organs such as the liver causing death in up to 200,000 people per year. With repeated water exposures the worm and thus egg burden is increased, meaning that the longer someone lives in an endemic area, the more likely they are to become seriously ill from this disease.

As the sun loomed overhead villagers took refuge in the shade or, children in particular, cooled off in the lake – and who can blame them! Lake water contact also frequently occurs as it is a main source of drinking, washing and bathing water, and fisher-folk need to make a living and provide for their families. Thus, cercariae exposure is high in Bugoto! Many pit latrines empty straight into the lake or their contents are washed into the lake as the wet season descends with terrific thunderstorms, promoting transmission of schistosomiasis as well as other faecal-oral communicable diseases. It was apparent why prevalence has been increasing over the past 10 years even though a control program has been implemented: praziquantel treatment alone is not the answer to this village’s schistosome problems. A combination of measures to eliminate this disease will be required. But what measures should be used with the financial resources available?

This is where the Lamberton lab (@PoppyLamberton) and the SCHISTO_PERSIST project come in. Our aim over the next few years is to assess the schistosomiasis situation in an attempt to uncover new ways in which to effectively control the disease in Bugoto, Mayuge and beyond. We want to find out what control methods are useful and practical in these areas through speaking to the locals and getting their input. By looking at who is infecting whom we aim to generate information using parasite genetic data that will help inform us on biological factors and social habits that drive transmission. This will enable us to focus education and control more efficiently. Sometimes people do not clear the infection with praziquantel treatment so we are also going to look at resistance and explore potential schistosome-microbiome-drug interactions too. This last part is the main focus of my PhD which I have just started this year.

Disease diagnosis is also very important for monitoring schistosomiasis, but the best diagnostics are often far from ideal in rural African communities. Improving field tests to increase their speed and accuracy is another key aspect that needs development to help achieve schistosomiasis elimination. Thus, engineers joined us from the University of Glasgow halfway through the trip to trial their new diagnostics in an attempt to address this issue.

So, it was all actions go in Bugoto! Data was collected, entered, corrected, and mapped. Stool samples were collected, stored, sieved, processed, analysed. Miracidia were picked one by one until there were thousands. Kato-Katz, parasite hatching, malaria screens, too many things to mention, but the kids were wonderful. Sweets were distributed as rewards, and most importantly they were also treated. It was indeed a very busy but successful month!

To conclude, the characteristic distended bellies typical of heavy schistosomiasis infections in the young and old were not the only visible sign of neglected tropical disease in this region; the red, swollen, glazed eyes of many villagers with trachoma was striking. Eggs of soil-transmitted helminths were noted in stool and malaria parasites were present in blood screens of the majority of school children. Goats, chickens and cows roam free in the streets and homes; clothes merge with rags and shoes are scarce. Poverty and disease is very real in Mayuge. Solving the problems here are not textbook. A successful community equation to cure a disease may not provide the same answer elsewhere, even if you input the same components. Parasites adapt to change, therefore in our effort to eliminate them we need to remember to be vigilant and flexible too.

And so it was a very weary but happy bunch of researchers, bags bulging with data, which arrived back to the Glasgow drizzle early on the 5th of March 2017, ready to crack on with the lab work and tackle the analyses, before out next trip back to this fantastic, welcoming and inspirational country. We very much look forward to meeting up with our amazing collaborators from the Vector Control Division when we venture back out to Uganda and would like to thank everyone involved for making the trip such a success.

Hmm it looks like your blog ate my first comment (it was super long) so

I guess I’ll just sum it up what I had written and say, I’m thoroughly enjoyung your blog.

Ias well am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to the whole thing.

Do you have any tips for novice blog writers? I’d really

appreciate it.

Excellent article. Keep writing such kind

of info on your blog. Im really impressed by your site.

Hey there, You’ve done an incredible job. I’ll certainly digg

it and personally recommend to my friends. I am sure they will

be benefited from this site.

Totally agree with the sentiments. its quite educative.

Thank you for you interest and encouragement

quite educative peace of article here, may all the efforts be done to put this on control

Der Artikel ist wirklich gut. Das Thema hat mich schon interessiert und ich konnte hier noch einiges weiterführendes finden. Ich bin schon sehr gespannt, weitere Neuigkeiten zu lesen. Danke und Grüße aus

Heidelberg Marco Feindler