This blog post is part of a series featuring new articles published in the LCNTDR Collection: Advances in scientific research for NTD control, led by the London Centre for Neglected Tropical Disease Research (LCNTDR). Stay tuned for updates on Twitter @bugbittentweets and @NTDResearch. You can find other posts in the series here.

Schistosomiasis

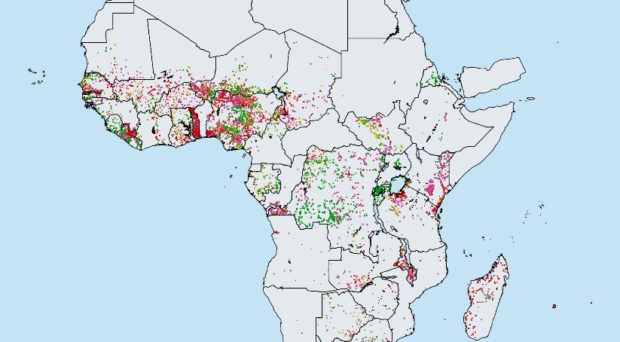

Schistosomiasis remains an endemic parasitic disease causing much morbidity and, in some cases, mortality. The helminth parasites may mature to adult worms in either the intestines (the species Schistosoma mansoni or S. japonicum) or the urogenital tract (S. haematobium).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has outlined strategies and goals to combat the morbidity and mortality induced by infection (WHO Helminth Control in school aged children manual). The first goal is morbidity control, which is defined by achieving less than 5% prevalence of heavy intensity infection in school-aged children (SAC). The second goal is elimination as a public health problem (EPHP), achieved when the prevalence of heavy intensity infection in SAC is reduced to less than 1%. Heavy-intensity infection (≥ 400 epg (eggs per gram) for intestinal schistosomiasis and > 50 eggs per 10 ml for urogenital schistosomiasis) can be detected using the Kato-Katz technique and urine filtration.

Treatment guidelines

The WHO treatment guidelines are primarily based on treating SAC only who typically harbor most infection (a target MDA coverage of 75% is recommended), and those at high risk of infection via mass drug administration (MDA) of the target groups using praziquantel (PZQ). The current treatment recommendations are treatment of SAC once a year in high prevalence settings ( ≥50% baseline prevalence among SAC), once every 2 years in moderate prevalence settings (10- 50% baseline prevalence among SAC) and once every 3 years in low prevalence settings (<10% baseline prevalence among SAC).

However, there is limited availability of praziquantel, particularly in Africa where there is high prevalence of infection. It is therefore important to explore whether the WHO goals can be achieved using the current guidelines for treatment based on targeting SAC and, in some cases, adults.

Impact of MDA on morbidity control and elimination.

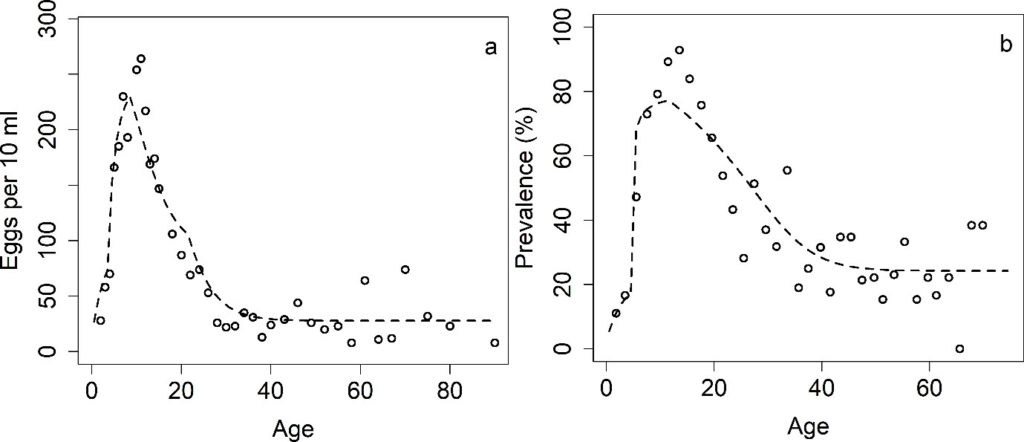

In our study we used an individual-based stochastic model, to explore the effect of MDA on S. haematobium transmission and determined the probability of achieving the current WHO goals of morbidity control and EPHP. We use two different age-intensity profiles of infection prevalence and intensity for S. haematobium (data from Misungwi (Kenya) and Msambweni (Tanzania)) with moderate and low adult burdens of infection (Figure 2).

We show that the key determinants of achieving the WHO goals are the precise form of the age-intensity of infection profile and the baseline SAC prevalence. We find that targeting SAC only can achieve the morbidity goal for all transmission settings, regardless of the burden of infection in adults. Additionally, we find that the higher the burden of infection in adults, the higher the chances that adults need to be included in the treatment programme to achieve EPHP.

In low transmission settings, treating 75% of SAC every 3 years, can achieve the EPHP goal with a high probability, regardless of the age-intensity profile of infection.

In moderate transmission settings, the probability of achieving the EPHP goal depends on the precise form of the age – intensity of infection profile. For a low burden of infection in adults, it is possible to achieve this goal but for moderate burden of infection in adults, this can only be done if the programme is expanded to include 40% MDA coverage of adults.

In high transmission settings, we find that the results depend on the burden of the intensity of infection in adults and the baseline prevalence. For a low burden of infection intensity in adults, the stochastic model predicts that EPHP can be achieved within 15 years of starting treatment for baseline SAC prevalence between 50% and 70%. If we increase the baseline SAC prevalence above 70%, it is necessary to adapt the treatment protocol by increasing SAC/adult coverage and/or increasing treatment frequency to more than once a year.

The study featured in this blog post has been just published in the LCNTDR Collection: Advances in scientific research for NTD control, led by the London Centre for Neglected Tropical Disease Research (LCNTDR). The collection has been publishing in Parasites & Vectors since 2016, and releasing new articles periodically. This series features recent advances in scientific research for NTDs executed by LCNTDR member institutions and their collaborators. It aims to highlight the wide range of work being undertaken by the LCNTDR towards achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals as well as supporting the objectives of the World Health Organization road map for neglected tropical disease 2021-2030.

The study featured in this blog post has been just published in the LCNTDR Collection: Advances in scientific research for NTD control, led by the London Centre for Neglected Tropical Disease Research (LCNTDR). The collection has been publishing in Parasites & Vectors since 2016, and releasing new articles periodically. This series features recent advances in scientific research for NTDs executed by LCNTDR member institutions and their collaborators. It aims to highlight the wide range of work being undertaken by the LCNTDR towards achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals as well as supporting the objectives of the World Health Organization road map for neglected tropical disease 2021-2030.

The LCNTDR was launched in 2013 with the aim of providing focused operational and research support for NTDs. LCNTDR, a joint initiative of the Natural History Museum, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the Royal Veterinary College, the Partnership for Child Development, the SCI Foundation (formerly known as the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative) and Imperial College London, undertakes interdisciplinary research to build the evidence base around the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of NTD programmes.

You can find other posts in the series here.

Comments