Leishmaniasis, is the third most important vector-borne disease. It is estimated that worldwide there are 1.5 to 2 million cases annually, with up to 350 million people at risk of infection. It is found in every continent except Australia and Antarctica and is caused by more than 20 different species of parasitic protozoa of the genus Leishmania. The species differ depending on the region and type of disease they cause. It is included in the WHO’s list of Neglected Tropical Diseases, along with others such as African Sleeping Sickness, Lymphatic Filariasis and Rabies.

Over 90% of cases are reported from five developing countries; Sudan, Brazil, Bangladesh, India and Nepal, however it is endemic in many more, including Ghana.

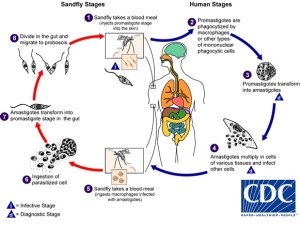

The disease becomes established in humans following the bite of infected phlebotomine sandflies, which regurgitate parasites into the skin, allowing the parasite to continue the lifecycle within the human host. This then stimulates the immune system, in particular macrophages, inducing an inflammatory response.

The term ‘Leishmaniasis’ encompasses multiple clinical syndromes, there being three main forms of the disease; cutaneous, visceral and mucocutaneous. All these result from infection of macrophages in the dermis, naso-oropharyngeal mucosa and throughout the reticuloendothelial system.

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL)

CL is the most common form of leishmaniasis, with one million cases reported in the last five years. It is a dermal manifestation that causes skin lesions, usually developing within several weeks following exposure. Lesions evolve from papules to nodular plaques and ulcerative lesions which can be covered by a scab/crust that generally results in scarring. The predominant etiologic agents for this form include L. tropica, L. major, L. aethiopica as well as L. infantum and L. donovani.

Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL)

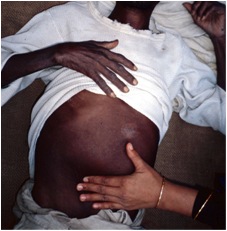

VL is the most severe form, affecting the vital organs of the body (spleen, liver, bone marrow) and is primarily caused by L. donovani and L. infantum.

Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis (ML)

ML is the most destructive form, whereby mucous membranes in the nose, mouth and throat are partially or totally mutilated. This occurs through the dissemination of parasites from the skin the naso-oropharyngeal mucosa and is normally cause by species in the Viannia subgenus.

Different/New Species

The gold standard diagnostic method involves staining of patient samples and confirmation of parasites using microscopy, however this doesn’t allow for DNA sequence evaluation and hence more specific information about the type of species. As there are several different causative species of leishmaniasis it is useful to utilise molecular techniques, such as PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction), when diagnosing suspected cases to ensure the correct form is confirmed, and hence, the most appropriate treatment plan is put in place.

Using PCR analysis following cultivation of the parasites collected from patient samples, one research group has recently isolated a suspected new species of Leishmania in the Ho District of the Volta Region, Ghana.

The main focus of the study was to isolate and characterise parasites causing cutaneous leishmaniasis in Ghana, a significant emerging disease in this region. Samples were taken from a large cohort of patients suspected of having CL, and were subsequently analysed to confirm the presence of the disease, caused by species typical of CL. Additionally, lesion aspirates were collected from three individual patients and used to establish promastigote cultures. Following this, amplification from each isolate was performed across a specific region of DNA known to give species-specific patterns in Leishmania.

The results showed all three isolates had a banding pattern different from that in a wide range of reference species examined including L. infantum, L. donovani, L. amazonensis, L. mexicana, L. braziliensis and L. guyanensis, indicating the potential representation of a new species.

This finding was further explored through phylogenetic analysis, which showed the new-found parasites to be within the L. enrietti complex, a possible new subgenus of leishmaniasis-causing parasites. Finally, it was concluded that these isolates represent a new species of human-infective Leishmania in Ghana, likely to be responsible for the majority/all of the cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Ho district.

The probability of finding the presence of other species is currently not strong as typically only one species is found in a particular landscape and ecological niche. However, multiple species may be geographically sympatric and the researchers acknowledged that more human isolates and epidemiological studies are required to fully assess this possibility.

What does this mean in terms of the disease?

This new finding, which could confirm the first new species to be isolated in Africa for over 40 years, also gives rise to the possibility that there could be further species present in Africa that are yet to be isolated. This could present problems, for example issues associated with anti-leishmanial drug resistance. Additional species could cause difficulties in treatment strategies due to growing evidence of the therapeutic response being species and perhaps even strain specific and different species may have varying or unknown severity levels. Additionally, as HIV is also prevalent in Ghana, co-infection could be a potential source of the emergence of drug resistance.

The local name of the symptoms caused by the newly isolated species, ‘agbamekanu’ is also of interest; meaning ‘gift from somebody who has returned from a journey’ it refers to the local belief that the disease has been brought in from neighbouring Togo, as travel across the border is relatively frequent. However the current pattern of infection likely reflects an exposure of naïve individuals to what has become an established endemic focus in Ghana.

Comments