The G7 met on June 8, 2015 and reaffirmed their commitment to fight against neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). Neglected tropical diseases are a group of 17 infectious diseases that thrive mainly amongst the poorest populations of the world. They are endemic in 149 countries, affect 1.4 billion people, and are costing developing economies billions of dollars every year. They include Chagas disease, dengue, chikungunya, sleeping sickness, leishmaniasis and a range of helminthic diseases. Such helminthic diseases have been the focus of a paper recently published by Peter Hotez and coauthors in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases highlighting the “worm index” and its association with other indices measuring development. We caught up with him to ask about his new paper and it’s significance.

Q: In your recent paper published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, you highlighted a strong association between a “worm index” representing the frequency of helminthic infections and impaired human development across countries. Could you please elaborate on what you did and what you found?

A: Our recent paper is an extension of earlier observations that chronic hookworm infections lead to reduced future age earning and worker productivity in the context of poverty, but the equation goes the other way as well since these infections also can contribute to poverty. This paper is an attempt to quantify this connection. We used WHO data on the prevalence of helminthic diseases, combined into a single “worm index”, and lined that up against the Human Development Index (HDI), another complex metric including education and development for the 25 largest countries. What we noticed was a striking inverse association where as the HDI goes down, the worm index goes up, and vice versa. We thought that this was quite interesting, even though it does not prove cause-and-effect. I personally believe that the equation goes both ways, that as worms reinforce poverty, poverty also reinforces worms. But we thought that the information on this associationwas useful, particularly now that we’re entering into the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and it’s important to get helminthic infections and other NTDs as prominent components of the SDGs.

Q: The question of cause-and-effect is particularly interesting. Do you believe that the worms are relevant in terms of causing poverty, or do these populations have worms because of the poverty? Do you believe that the worms might be responsible for a poverty trap?

A: I think it goes both ways, although I can’t prove it. In a different perspective, we can consider worms as the biomarkers of reduced development. I think the worms are responsible for a poverty trap. In fact, studies by Hoyt Bleakley at the University of Michigan found that chronic helminthic infections in the United States at the turn of the 20th century reduced future wage earnings by 40%. Similarly, Michael Kremer at Harvard has found that in Kenya, helminths have an effect on educational attainment and performance at school, and through that mechanism on future economic developments. It’s an understudied, but very important topic in my opinion. Our study was an attempt to quantify that at the macro scale.

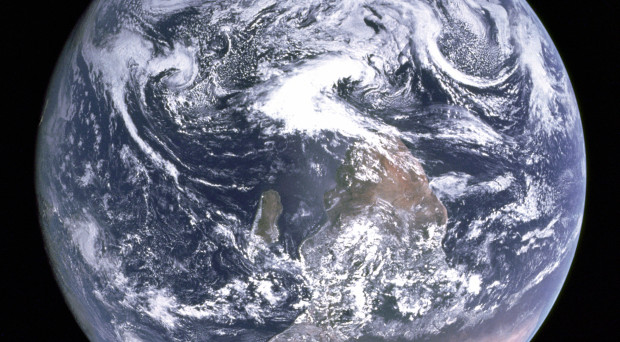

Q: As many others, I have followed your work during the last decade on neglected tropical diseases. One aspect that intrigued me most about your work was the study of neglected diseases in poor populations living in wealthy countries, such as in the US. I heard this described using the concept of ‘blue marble health’. Could you please explain what ‘blue marble health’ is and how is it useful to think about neglected diseases of poverty?

A: The concept of ‘blue marble health’ describes a new global health paradigm suggesting that all economies are rising but that each one leaves behind a bottom segment of society that face similar disease burdens globally. It has to do with the fact that we’re starting to see neglected tropical diseases in wealthy countries, especially among the poor living among the wealthy. In fact, we just published a paper in Microbes & Infection in which we showed that this is not only true for NTDs, but also for the Big Three diseases (HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria), where approximately half of all global cases occurs in one of the G20 countries and Nigeria, which is not a G20 country, but has a massive economy. The world is changing, and it’s no longer useful to talk about countries as “developing” vs. “developed” according to the old paradigm. Instead, both in countries previously considered “developing” and “developed”, poor and wealthy populations tend to spatially segregate into different areas, creating pockets of extremely poor populations even within developed countries. Most people living in extreme poverty now live in G20 countries. These extremely poor populations are subject to similar disease burdens regardless of which country they live in. Therefore, they face similar problems and need similar support to overcome those. Helminthic diseases and other NTDs (including e.g. Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, dengue) are now concentrated in these areas of extreme poverty.

A: The concept of ‘blue marble health’ describes a new global health paradigm suggesting that all economies are rising but that each one leaves behind a bottom segment of society that face similar disease burdens globally. It has to do with the fact that we’re starting to see neglected tropical diseases in wealthy countries, especially among the poor living among the wealthy. In fact, we just published a paper in Microbes & Infection in which we showed that this is not only true for NTDs, but also for the Big Three diseases (HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria), where approximately half of all global cases occurs in one of the G20 countries and Nigeria, which is not a G20 country, but has a massive economy. The world is changing, and it’s no longer useful to talk about countries as “developing” vs. “developed” according to the old paradigm. Instead, both in countries previously considered “developing” and “developed”, poor and wealthy populations tend to spatially segregate into different areas, creating pockets of extremely poor populations even within developed countries. Most people living in extreme poverty now live in G20 countries. These extremely poor populations are subject to similar disease burdens regardless of which country they live in. Therefore, they face similar problems and need similar support to overcome those. Helminthic diseases and other NTDs (including e.g. Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, dengue) are now concentrated in these areas of extreme poverty.

Q: The neglected diseases of poverty that are mentioned in the papers I’ve read are mostly infectious diseases, such as helminthic diseases, Chagas disease, dengue, leprosy, etc. I do wonder if non-infectious diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, or even psychological disorders such as depression or schizophrenia could also be considered neglected diseases of poverty, since patients living in poverty cannot afford treatment and care. What is your opinion of this suggestion?

A: I absolutely agree. In fact, if I had the time and the staff and the resources to help with it, I would really like to do a deeper dive into the NCDs (non-communicable diseases) as well. I originally focused on neglected tropical diseases in the concept of ‘blue marble health’, then I extended it to the “big three diseases”, and I think it would be a very interesting exercise now to see if it also holds up for the NCDs as well, and I think there’s a possibility that it does. Look at heart disease or hypertension, I mean this is one of the reasons why African-American men are dying younger than their white counterparts; or the rates of breast cancer among African-American women; so I do think that this concept of ‘blue marble health’ could extend to multiple health disparities. We haven’t started doing this yet, but it’s something that I’m hoping to do. The key is to get good WHO numbers on things like heart disease or cancer by geography, or if those are not available, then work with the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, that we also work with, to see if they have those numbers. This creates an opportunity to create some shifts in policy: at the annual summit of the G20 countries this should be a topic, because if the G20 countries would take greater ownership of their own NTDs, it would make a huge difference. Basically, if you took the G20 countries and their neighbors, and got them to renew their own commitments to their own diseases, we could see half the world’s disease burden evaporate. And the other half could evaporate if these same G20 countries also stepped up creating mechanisms to support research and development. There’s a moral imperative, but these diseases also keep back the economies of these countries. This is where the brilliance of someone like a Jeffrey Sachs comes in: when he was heading the Commision on Macroeconomics and Health, he was one of the first to point out how certain types of diseases are actually trapping people in poverty and causing poverty – and now we’re kind of extending that to the concept of ‘blue marble health’. We really only started with helminthic diseases because that’s my background, as I was developing vaccines for these, and now we’re branching out.

Q: I know many researchers, including myself, who are passionate about reducing health inequality both in close proximity as well as globally, through addressing neglected diseases of poverty. What recommendation could you give to researchers planning to enter this field about the challenges involved? What resources can you recommend that would allow them to link with researchers already working in this field? What are the most obvious research needs and gaps to be filled?

A: I’m also trained as a laboratory investigator, as a laboratory scientist. I develop vaccines for neglected tropical diseases. I’ve gone into the policy arena driven by necessity after the Millenium Development Goals when they called the diseases I was working on ‘other diseases’. I realized that unless I work on advocacy and policy myself, nothing’s going to happen about them. And we’ve been very successful in getting NTDs on the international radar screen. So I find myself in the unique position that I’m both a laboratory investigator, with everything that goes with that, and also an international spokesperson in the policy arena. The biggest challenge to me right now is trying to maintain a footing in both spheres. What I enjoy most in this existence is probably that it forces me to interact with people that I wouldn’t necessarily interact with otherwise, such as economists, social scientists, experts in political economy. In terms of resources, I can recommend my earlier book on neglected tropical diseases called “Forgotten People, Forgotten Diseases”, and I’m hoping to work on a new book specifically on this concept of ‘blue marble health’; or some of my previous papers on the topic. The most obvious research needs are to uncover exactly how do these infections cause poverty, which I think is not yet well established; trying to understand the mechanisms, where social science research is going to be very important. The other research needs are developing technologies to combat these diseases, e.g. new vaccines, which I actually call anti-poverty technologies, anti-poverty vaccines. This is a new concept that a vaccine could be used not only to improve public health, but also to lift people out of poverty. On the policy side, we need to understand how to gain access to the elected leaders of the G20 countries better to actually shape international policy.

After such an extensive discussion with Dr. Hotez, we can conclude that there is a lot of potential as well as work ahead on highlighting ‘blue marble health’ and health inequalities in terms of the NTDs, infectious diseases, but even NCDs in general. Hopefully, the 2015 G20 Summit in Turkey will make similar commitments in terms of NTDs as the G7 countries just did, and move towards reducing their burden globally. I’m personally looking forward to reading Dr. Hotez’s upcoming book on the concept of ‘blue marble health’, and grateful for a great conversation!

Comments