You can also listen to Dave’s Palaeocast where he interviews one of the authors:

Eurypterids, or ‘sea-scorpions’ are an extinct group of chelicerates: the group containing the terrestrial arachnids (such as spiders and scorpions) and the aquatic ‘merostomes’ (represented today solely by the horseshoe crabs).

They bear a gross-morphological resemblance to scorpions (hence the informal name) but, in being aquatic, may have shared more in common with horseshoe crabs. They inhabited the waters of the Paleozoic Era and were typically scavengers or predators.

Some crawled along the sea floor and possibly even up on to land to spawn, like horseshoe crabs do today, whilst others developed rudimentary paddles and were capable of limited swimming.

These were large, intimidating eurypterids, typically measuring between 0.75 and 1.5 metres, and were undoubtedly predatory.

Most eurypterids were quite small and unremarkable, but some genera, such as Pterygotus and Jaekelopterus grew to incredible sizes; the latter reached an estimated 2.5m (8’ 2”) and is still the world’s largest-known arthropod.

They could also be quite hellish in appearance, with the megalograptid family best exemplifying this. These were large, intimidating eurypterids, typically measuring between 0.75 and 1.5 metres, and were undoubtedly predatory.

They possessed large appendages with multiple inward-pointing spines, perfect for the ambush and capture of prey. They were the first family of eurypterid to appear in the fossil record and so have typically been positioned at the very base of the eurypterid ‘family tree’ as the most ‘primitive’.

An exciting new discovery

The newly described Pentecopterus was discovered close to Decorah, Iowa, and dated at 467.3 – 458.4 million years old (the Darriwilian stage of the Middle Ordovician period), is the oldest eurypterid yet-found.

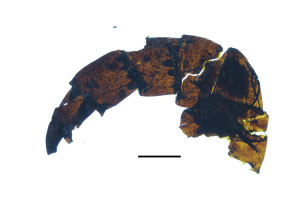

Unfortunately it is not complete, but preserved as fragmentary remains and parts of the animal remain unknown, but with over 150 specimens, we’ve got a good idea of its overall morphology. It is estimated to have measured up to 1 metre in length and possessed the large inward-pointing spines and a specific pattern of ornamentation that identifies it as a member of the aforementioned megalograptid family. Unsurprising that the oldest eurypterid is a member of the family at the base of the tree.

This is probably as far as tabloid newspapers will get. “OLDEST SEA-SCORPION WAS PRIMITIVE KILLER.” But the scientific significance of Pentecopterus extends far beyond it being the oldest eurypterid yet-found and looking a bit scary.

The wider connotations of the discovery of Pentecopterus were revealed when it, and other eurypterids, were included within a phylogenetic analysis. These are hypotheses of the inter-relations of any given group of species based on the number of shared characteristics.

What the analysis shows is that due to a variety of anatomical features, the megalograptid family (including Pentecopterus) can now be considered to be part of a larger group called the carcinosomatoids.

The problem is that the megalograptids are classically at the base of the tree, but carcinosomatoids at the top. The implication of having to move the megalograptids higher up the tree to join the carcinosomatoids is that all the lowest branches of the tree must predate the upper branches.

Therefore Pentecopterus, though the oldest-yet found eurypterid, can’t actually be the oldest. We must consider older rocks still if we want to find the very earliest members of the eurypterid group.

An exceptionally well-preserved fossil

Despite this significance, these new discoveries and subsequent reinterpretations of the fossil record are actually commonplace. What makes Pentecopterus so unique is that on top of everything we’ve just discussed, it is exceptionally well preserved.

If you are acquainted with the fossil record, you’ll know that it is generally only ever the hard parts of organisms that get preserved: the skeleton inside the dinosaur, the teeth of sharks or the shells of snails.

Consider your own body and the importance of your soft tissues and organs; they are responsible for the majority your biological functions and ecological interactions. In the fossil record the majority of this information is lost.

Arthropods are unique in that they possess their hard parts on the outside. Their exoskeletons are not an inert protective covering, but are a dynamic and functional layer through which all of the animal’s interactions with the world outside are conducted (its ecology).

Pentecopterus, though fragmentary and without soft-part preservation, preserves the original cuticle (albeit altered chemically), and with it, a whole host of palaeoecological information.

How does it look?

Along the edges of the swimming paddles are lines of sockets, where sensory hairs probably would have inserted. These sockets were perpendicular to the paddle’s principle direction of movement, possibly feeling the flow of the paddle through the water, but also increasing its surface area.

On its ‘teeth’ are robust hairs all angled towards its mouth. These were likely able to taste, but their orientation also facilitated the movement of food. Over all the body are sockets from where sensory hairs would have protruded: some large, some small, some associated with cuticular thickenings. What we are observing is the variety of ways, and the variety of places, Pentecopterus interacted with its world.

Although it may be premature to describe the exact function of each hair, Pentecopterus provides us with a unique data-point for our understanding of the palaeoecology of the eurypterids. With further investigations into their exoskeletons, eurypterids have the potential to become the best known of all fossil organisms.

Quite surprising for something nearly half a billion years old!

Comments