The World Health Organization recommends annual mass drug administration in areas where soil-transmitted helminths (roundworm, hookworm, & whipworm) (STHs) infect 20% of school aged children. These parasites live in the intestines of human and are transmitted through eggs in faeces that hatch in soil where larvae find their next host. They cause a range of symptoms and are associated with poor cognition, stunting and anaemia.

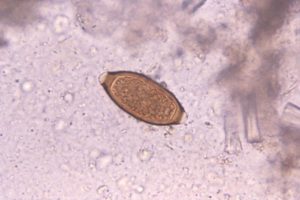

Determining if a person has STHs is done through examination of faecal samples for the presence of eggs.

It requires unique technical skills and is time intensive. Diagnostics are expensive and intractable at large scales, so mass drug administration (MDA) of albendazole is used. Albendazole can clear worms with minimal side effects, but mass treatment means that both infected and uninfected people receive treatment, adding costs to this intervention.

Research has argued that each 1GBP in treatment can result in a 6 GBP of benefits. These benefits include individual health benefits, like a reduction in anaemia and malnutrition. Deworming is also thought to improve school attendance and performance, increasing the likelihood of productivity during adulthood. Additionally, deworming can reduce pressure on the healthcare system by treating common infectious diseases

Although individuals and the community can benefit from treatment, there is an open debate of whether mass deworming should continue. A Cochrane Review was set up to systematically review primary research to provide evidence-based policy recommendations of whether MDA was the most effective.

The review of mass deworming found limited evidence for regular deworming treatment to improve average weight gain, haemoglobin or cognitive function. This raised a question of whether mass deworming was the best strategy.

However, there is a new meta-analysis that includes more studies than the Cochrane study and actually finds a positive effect of deworming. The authors also show that deworming is more effective at increasing weight gain than school feeding programs (36 times more on each dollar).

Whether or not to use limited resources on MDA programmes has been up for debate before and will continue to be debated when evidence is limited. The hope is that mass deworming reduces individual and community level burden- eventually reducing prevalence. As we move forward, it is important to optimise control of these diseases and pinpoint key measures to monitor and plan specific interventions.

In developing countries the school feeding programs forms the basis of infection due to poor hygiene, deworming is paramount