COVID-19 prompted impressive numbers of people in the UK to volunteer for clinical trials. They expect to see results, but open access to the results of clinical research still has a long way to go. For years, the standard conditions of ethical approval have required clinical trials to be registered and reported on the international system of public registries. Yet in 2018 the UK Parliament’s Science and Technology Committee criticised many UK universities and NHS bodies for ignoring these conditions on a grand scale.

But let’s celebrate what has happened. In the 21st century a niche preoccupation among journal editors and a few scientists has turned into an international movement towards transparency, and the UK has played an important part.

Iain Chalmers argued eloquently that under-reporting of clinical trials is unethical. High-quality research builds on previous methods and findings. Evidence-based practice relies on guidelines based on complete reporting and systematic reviews. Too much of the evidence from clinical trials is invisible to international science.

The ISRCTN registry

The ISRCTN registry began with an international meta-register created by Current Controlled Trials Ltd. BioMed Central (later renamed BMC) bought CCT. Its expert team in London supported the UK’s strong contribution to debates at the World Health Organization (WHO) resulting in an international standard for clinical trial registration.

With this consistent format, the international network of registries has shared over half a million study records via a WHO portal. While its search engine needs investment, it tells you a lot. Try it. Would you have guessed that 39,000 studies recruiting in the UK over the last decades would generate 82,000 records on worldwide registries? The UK is a leader in duplicate clinical trial registrations!

A big decision we made as owners was to go on contracting for a team in the UK. The US government’s National Library of Medicine made a thoughtful proposal to run ISRCTN as a subset of ClinicalTrials.gov. We decided to remain independent of government, industry and universities. Were we right?

ClinicalTrials.gov is the big beast among registries – but it is not a primary registry. Although the USA doesn’t accept the WHO standard, it contributes data for over half the studies on the WHO portal. ISRCTN contributes under 4%.

What ISRCTN shares with the US registry is international reach. Under 55% of studies on ISRCTN recruit in the UK and over 45% in 250 other locations. The price of ISRCTN’s independence is a registration fee. The fee also enables creation of a more complete, up-to-date and accessible record. ClinicalTrials.gov and other registries do not charge for registration since they are funded by governments or academic institutions.

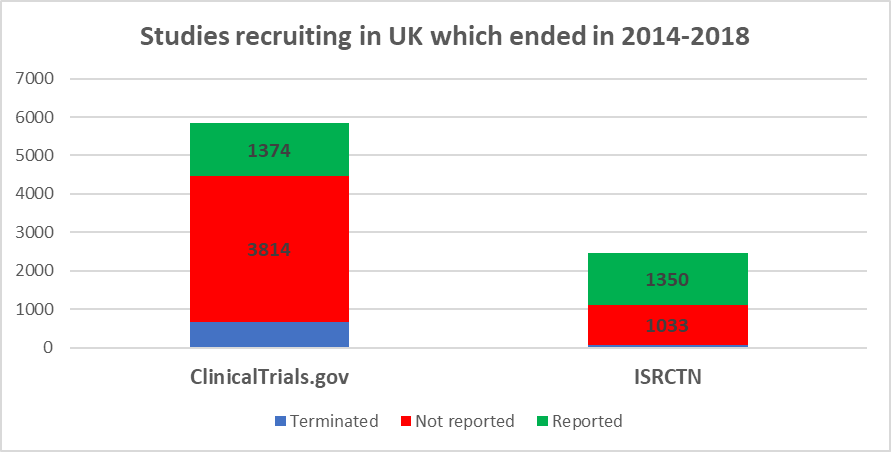

In 2019, British research teams chose ISRCTN for 550 studies recruiting in the UK. They chose ClinicalTrials.gov for over 1400. Those 1400 included over 800 studies funded by British charities, universities and NHS bodies. Even though many of the largest UK funders cover the ISRCTN fee either directly or in their grants, they didn’t use the UK’s primary registry.

Does this matter? Yes, because of under-reporting. Initially, WHO registries focused on the ethical duty to declare every study on a public register before it started. Now, we expect at least a summary report of results of every completed study. In 2015, WHO members agreed a statement on public disclosure of results. In 2017, a consensus statement from funders required results to be reported one year after the end of a trial.

Posting a results summary on a public register does not pre-empt publication. To promote reporting as well as registration, ISRCTN redesigned its website in 2014. The editorial team sends reminders when a report or update may be overdue. The website has received good feedback for ease of use at each stage.

What is to be done? The British Parliamentary Committee criticised the Health Research Authority (HRA) for not auditing research teams’ compliance with registration and reporting conditions. In a consultation, UK users specified the ISRCTN registry’s fee as the main barrier to registration.

Looking back at the last 20 years, the UK’s primary registry can be well satisfied with the service it offers. But can we go on charging individual fees for a WHO primary registry? A large majority of UK academics vote no, preferring a US government agency.

The responsibility for transparency in UK clinical research cannot sit on the HRA’s shoulder alone. It belongs to everyone.

To beat worldwide public health threats such as the coronavirus we need a massive worldwide collaborative scientific effort to find knowledge we can rely on. Will that lead to a renewed commitment to transparency, and to international reporting via the WHO registry network?

Comments