Ageism

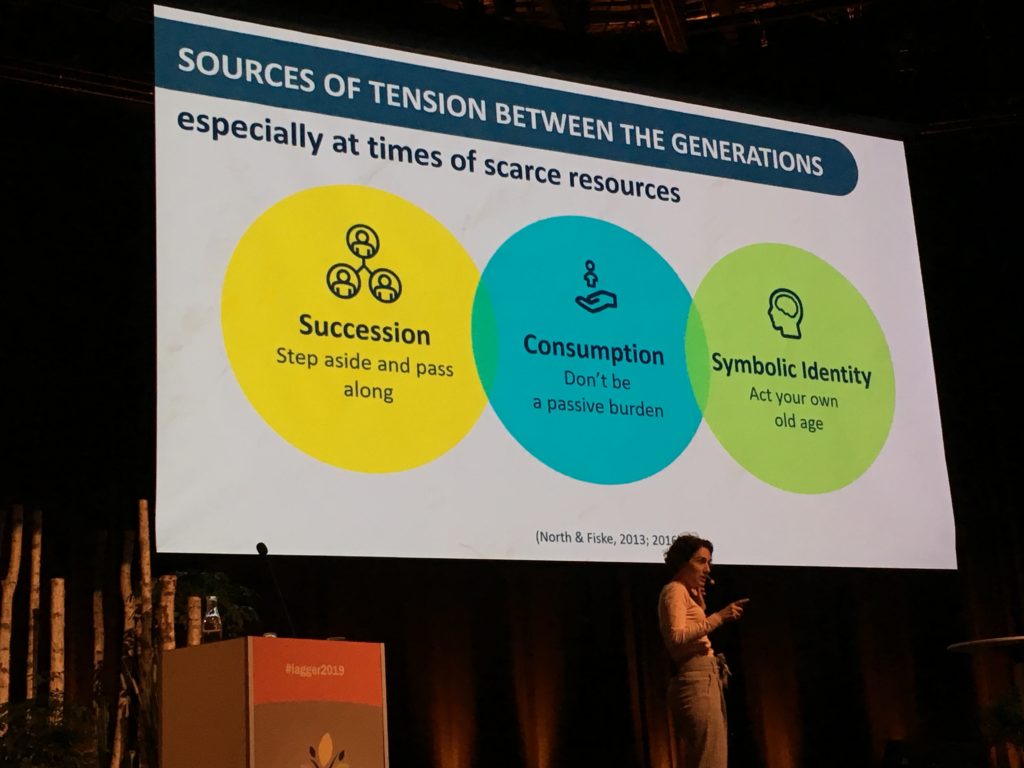

Prof. Liat Ayalon delivered an excellent keynote on ageism. According to a 2016 survey by the WHO, approximately 60% of older people feel they’re not respected. Ageism has an impact on health too, given that this discrimination can be expressed by healthcare- and social workers. For instance, the stigmatization that older people utilize more healthcare resources means they are often less likely to be offered more advanced forms of therapy, and are more likely to receive a differential diagnosis than a younger individual for the same condition due to inherent assumptions.

More directly, older people with a negative perception of their own age are more likely to die earlier than those with a positive perception. Language and culture are key factors here; the words we use when communicating with older people are important, as is fostering a more tolerant and accepting environment; however, the concept of ‘ageism’ doesn’t exist in all languages, which makes this more complex. From a societal perspective, older people have a lot to offer including experience, wisdom, and the preservation of traditions, and so we need to change the way we think, feel and act towards older people.

Loneliness

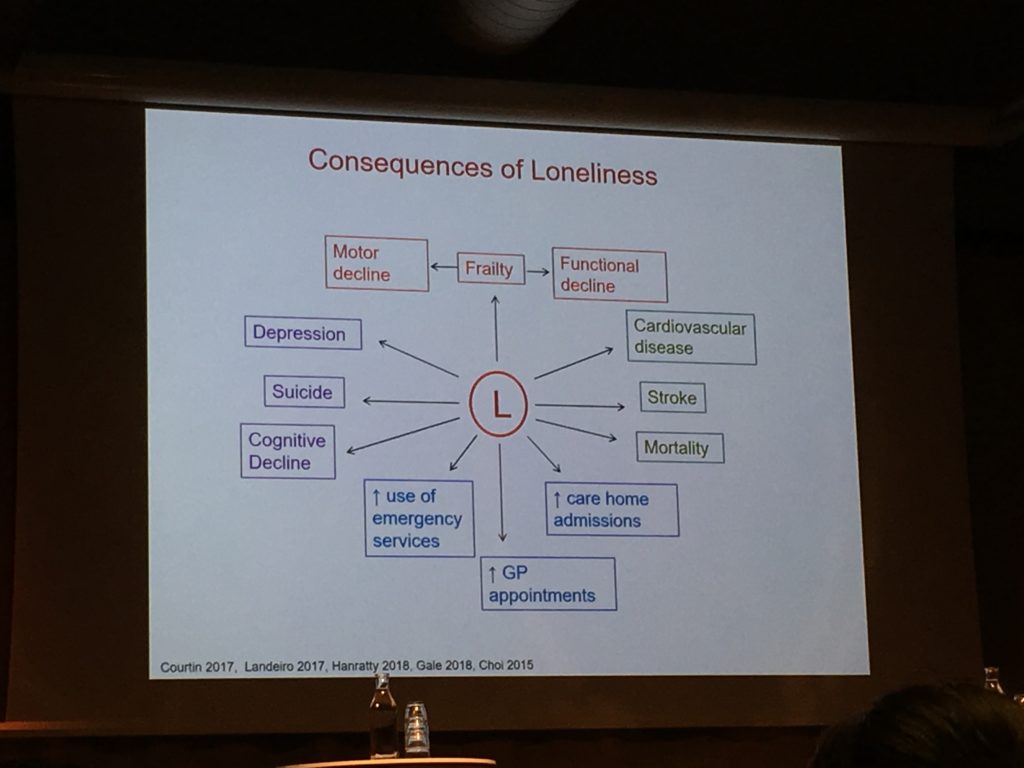

The topic of loneliness was covered in great detail during the congress, and Dr. Tahir Masud discussed the prevalence of loneliness in the UK. Approximately 5-16% of people over the age of 65 experience loneliness most of the time, whilst a third experience it sometimes. There are a number of triggers including bereavement, retirement, disability, moving into care, poor health, and a fear of falling.

The consequences of loneliness can be physiological as well as psychological, and there are several scales used to measure it – such as the De Jong Gierveld Scale (DJGLS) and the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) questionnaire. Applying these to secondary care showed that a third of ‘falls and bone clinic’ patients experience loneliness most of the time; this goes up to 50% in geriatric ward in-patients. Thus, it is clearly important for governments to create initiatives to tackle loneliness and social isolation. To that end, former Prime Minister Theresa May appointed a ‘Minister for Loneliness’ (possibly the first minister of its kind). £20 million was invested into a loneliness scheme, and loneliness was embedded into all government departments. The drive for this focus was largely provided by the late MP Jo Cox, who was an advocate for tackling loneliness.

Prof. Sylvie Bonin-Guillaume discussed the importance of also assessing the loneliness of caregivers, particularly given their high percentage of psychotropic drug use and prevalence of frailty. Also, a consequence to care recipients is an increased risk of emergency room visits. However, social support is less accepted by caregivers experiencing loneliness and they perceive their needs to not be as well addressed (compared to their non-lonely counterparts.) What about the risk factors? Prof. Marja Aartsen presented a latent class growth analysis on loneliness trajectories using data from the Norwegian Study on Life-course, Ageing and Generations (NorLAG). Being female and having poorer subjective mental health (using the MCS-12) increased the risk of a negative trajectory, whilst having a partner was found to be protective.

Prof. Charles Waldegrave presented data from New Zealand, using the NZLSA cohort. Higher levels of both physical and mental health are associated with lower levels of loneliness. Conversely, high vulnerability to abuse and discrimination, lower living standards, and higher levels of hardship result in increased loneliness. What can be done? Increasing general recreational activities and improving economic living standards are both associated with decreased loneliness – and both are modifiable risk factors from a policy standpoint, but are often not as well funded compared to health interventions.

Sarcopenia

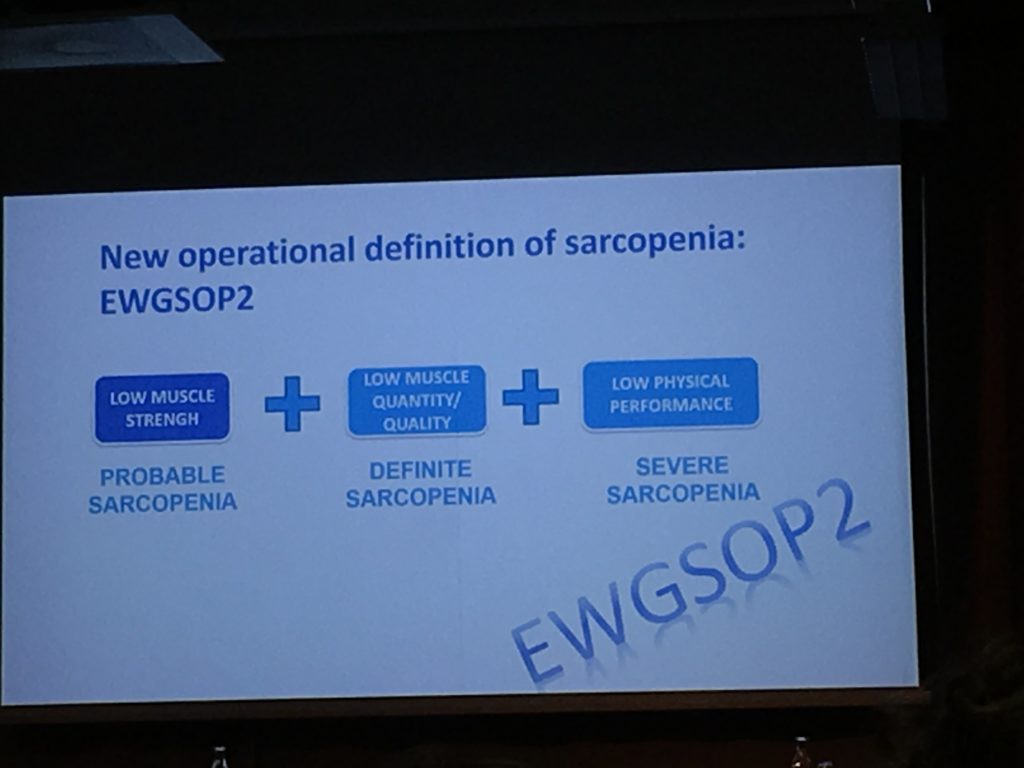

The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) presented the revised definition of sarcopenia. According to this, sarcopenia is defined as muscle failure and is linked with an increased likelihood of adverse outcomes, such as falls as mortality. To aid diagnosis, they’ve proposed a new clinical algorithm: Find cases, Assess, Confirm, and Severity (F-A-C-S). The new definition also distinguishes between acute- and chronic sarcopenia, and provides cut-off points for diagnosis.

Dementia

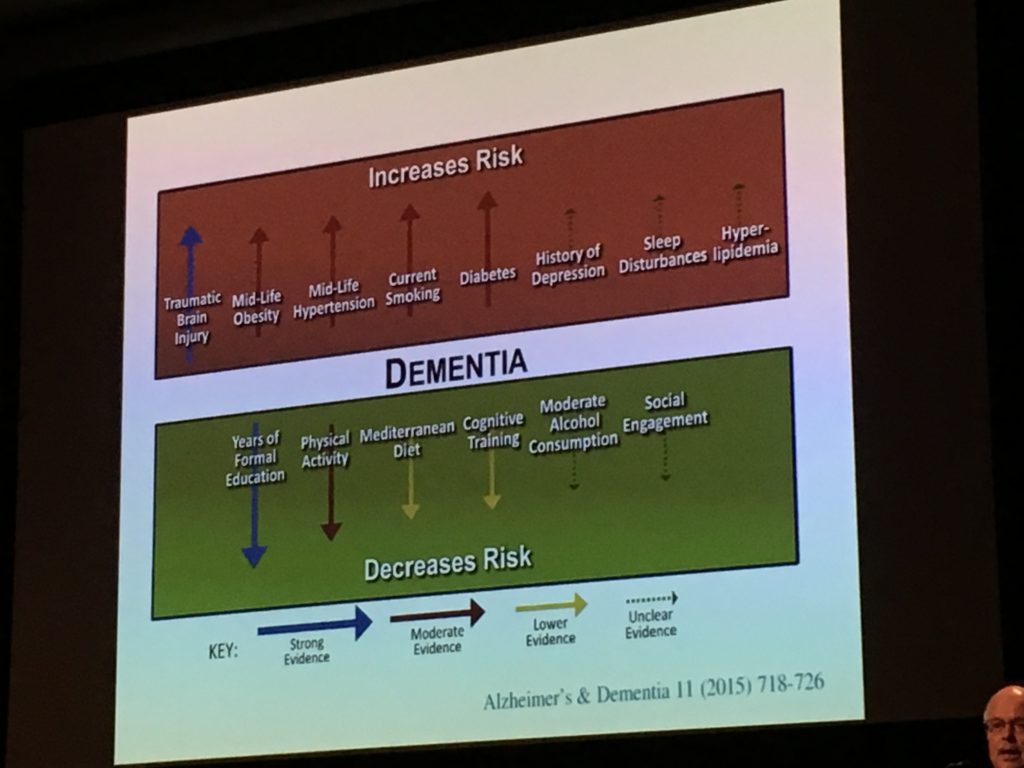

Prof. Peter Nilsson discussed the association between hypertension and poor cognitive function (in particular mid-life hypertension and later life dementia). Statin therapy may reduce the risk of dementia, and lifestyle interventions may also be effective.

To that end, Prof. Alina Solomon presented the results of the FINGER trial – a multidomain lifestyle intervention that led to an overall decrease in dementia risk. Further analysis showed the intervention is also cost-effective from a societal perspective. Dr. Silke Kern presented some interesting data from the H70 cohort, investigating the utility of neurofilament light protein (NfL) as a biomarker for the preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease. In cognitively normal patients, NfL levels were higher in those with evidence of neurodegeneration and tau phosphorylation.

This congress – with over 1600 delegates from 64 countries –provided an excellent forum to discuss a range of stimulating topics, and highlighted the prevalence and consequences of discrimination against older individuals; the need to find more effective solutions to combat loneliness and social isolation; and advances in sarcopenia and dementia that may aid diagnosis and treatment.

Comments