Imagine going out for drinks at a pub or bar. You order a glass of wine. “Large or small”, the waiter asks. You think for a moment, or maybe you don’t need to think at all. “Large” you reply; perhaps you think it’s better value for money; or perhaps “small” just doesn’t sound enough. But if you’re in England, a large glass of wine usually equals a 250-millilitre (ml) portion, one-third of a standard 750 ml bottle of wine. And if you have a second glass, then you will have consumed a whopping two-thirds of a bottle, perhaps without even realising it.

But what if the largest portion you could order was smaller, say capped at 175 ml? Would that have made a difference in how much you drank on a given evening? Would you have realised that the portion was smaller, leading you to order more? Or would you have been content to consume your usual number of glasses, not thinking twice about exactly how many ml each contained?

People eat more food when served larger portions and when eating from larger packages or larger plates. This was shown in a Cochrane systematic review conducted in 2015. At that time, no studies had examined the impact of changing the size of anything related to alcohol – the size of glasses, bottles or servings. Since then, a number of studies have been conducted, which we reviewed in 2022.

Evidence from real-world settings suggests that using smaller wine glasses can help people drink less wine in restaurants, as well as at home. Drinking from smaller 500 ml bottles (as opposed to the usual 750 ml size) may also help people to drink less at home. Reducing the size in which alcoholic drinks are served in bars and restaurants appears promising but at the time there was no real-world evidence for this.

We addressed this lack of real-world evidence by conducting a study, registered at the ISRCTN registry, in which we asked 21 pubs, bars and restaurants in England to remove the offer of their larger serving size of wine by the glass – usually 250 ml – from available options for 4 weeks.

We compared the total daily volume of wine sold during the intervention period to that sold during non-intervention periods. We found that removing the largest serving size of wine by the glass (usually 250 ml) reduced the volume of wine sold by 7.6%, without any evidence that sales of beer or cider or total daily revenues were affected.

Although these findings highlight the potential of the intervention for reducing alcohol consumption at the population level, it is unknown whether similar effects would result from removing the largest serving size for other drinks such as beer.

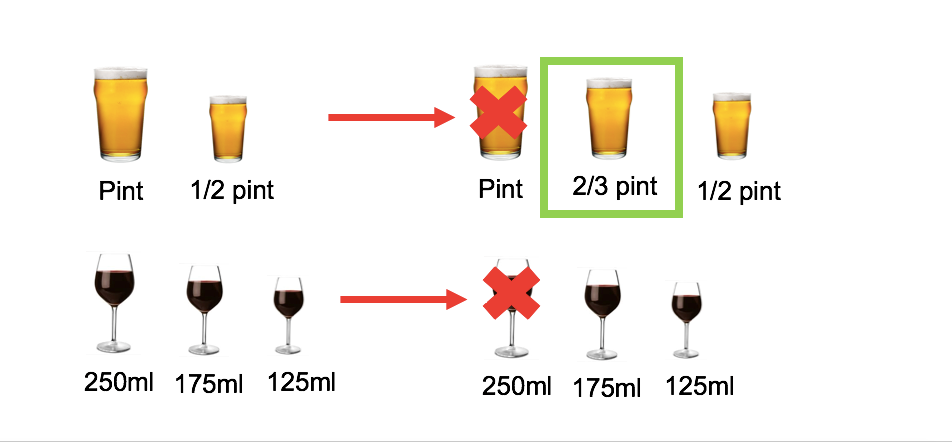

We attempted to conduct a study to estimate the impact of removing the largest serving size for draught beer – the imperial pint (568 ml) – and replacing it with a two-third pint measure. However, after contacting almost 2000 pubs, bars and restaurants in England, we were unable to find any willing to do this and ‘mess’ with the ‘iconic’ pint.

The pint has been the standard and most popular serving size for beer in England for centuries. Indeed, “going for a pint” has become synonymous with “going for a beer” in British culture. For context, in England, draught beer must be legally available to be sold in pints (568 ml) and half pints (284 ml). One-third (189 ml) and two-third pints (379 ml) can also be sold, but licensed premises are not legally obliged to sell these.

Faced with this challenge, we instead ran a study in which we asked 13 licensed premises to add a two-thirds pint option (379 ml) for 4 weeks to their existing range while leaving pints available. This had no impact on the volume of beer or cider sold.

Around 4 years after our initial requests to licensed premises to participate in a study involving the removal of pints, our renewed attempts last year proved more fruitful, perhaps reflecting the changing times of the post-pandemic era in which payment for participating in a study has a greater allure. Or perhaps due to our improved skills of persuasion.

Whatever the reason, we were successful in running a study, registered at ISRCTN, in which 13 pubs, bars and restaurants in England removed the largest serving size of draught beer (one imperial pint or 568 ml) from their existing ranges so that the largest size available became the two-thirds pint. Where two-thirds pints were not usually served, premises introduced this serving size in conjunction with removing pints. The much-anticipated results are expected to be published soon but preliminary analyses suggest that the intervention was successful in reducing the daily volume of beer sold.

Taken together the results of these studies suggest that removing the largest size in which wine and beer are served in pubs, bars and restaurants and replacing it with a smaller size can help people keep their drinking in check. Is it perhaps time we consider alcohol licensing regulations that cap the size at which wine and beer by the glass are served – one size lower than their current caps?

Comments