Which came first – the chicken or the egg?

This age old question is always a good one to start a lively discussion. Another question which generates almost as much discussion – is child obesity due to environmental factors or to individual factors?

Unlike the chicken/egg dilemma, in which you have to choose a side, with childhood obesity, it looks like both individual behaviors and environmental factors contribute to the problem.

Researchers at the Michael & Susan Dell Center for Healthy Living at the University of Texas School of Public Health (UTSPH), USA, have been working to address the issue of child obesity through traditional channels of research, education and community outreach, as well as a unique private-public partnership with the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation.

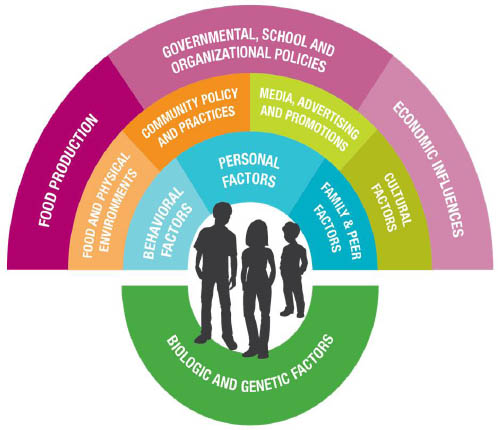

Our current work is highlighted in the eight articles that comprise a special issue of the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. The issue, titled “The Science of Childhood Obesity: An Individual to Societal Framework,” provides a research framework and further insights into solutions for child obesity, with a focus on diverse and low-income populations.

Although recent progress has been seen in obesity prevention efforts, childhood obesity is still a significant public health problem, with almost one-third of children ages 2 to 19 classified as overweight or obese in the United States.

These rates are even higher in Texas, USA, where much of our work is focused. Thus, it is imperative that we continue research efforts to elucidate more proximal determinants of childhood obesity, as well as intervention strategies to address them.

So, what does our research show?

Students in schools that have state-level bans on sodas without regulating the sales of other sugary drinks compensate by consuming more sports, energy drinks and sweetened coffee drinks. The current emphasis on banning sodas in schools may be counterproductive if these policies are not comprehensive and applied throughout the school environment.

Residents of low-income communities report high nutrition knowledge and preference for healthy foods, but have difficulty obtaining them because of high prices, low quality of foods available in their neighborhoods, and the lack of access to food stores near them. As a solution, residents prefer large grocery stores rather than convenience stores, but also are open to farmers’ markets and community gardens as ancillary approaches.

Children who are overweight or obese appear to watch more television because of social factors and friendship dynamics. In this study, children who spent more time with friends were more likely to be physically active, and less likely to be obese. So, parents should focus on preventing social isolation through prevention of weight-related bullying and acceptance of children, regardless of body size, as well as turning off the television.

Children in low-income schools are more likely to be obese, regardless of family income. Thus, the school environment itself is an important target for obesity prevention efforts.

Family behaviors, specifically social and physical aspects of the home food environment, are associated with consumption of healthy foods. Social aspects include family meals, whether or not families watch television during meals, and whether the child has eaten at a restaurant during the previous day. Physical aspects include whether healthy or unhealthy foods have been served during mealtimes. In addition, neighborhood food access is associated with child dietary intake.

Children who are obese are more likely to be absent from school, and are more likely to have school problems and lower levels of school engagement. School administrators should recognize that child obesity affects school academic performance, and prioritize obesity prevention efforts in the school environment.

When self-reporting height and weight data for calculation of body mass index (BMI), adolescent boys tend to underestimate their height and adolescent girls tend to overestimate their weight. Our study team developed correction equations to increase the sensitivity of self-reported measures.

Three themes identified

It should be recognized that determinants of childhood obesity are not one-dimensional, and other factors may be involved.

These articles are further summarized in Perry et al., in which three main themes are introduced. First, children in low-income groups are more likely to be overweight or obese, and less likely to have access to resources for healthier foods and opportunities for physical activity.

Second, environments which surround children (home, school, policy) can have a significant and major impact on weight status and dietary intake on children, irrespective of socioeconomic status.

Finally, it should be recognized that determinants of childhood obesity are not one-dimensional, and other factors may be involved.

So, where do we go from here?

This body of work, taken as a collection, can be seen as a call to action for both more focused research questions as to the causes of childhood obesity and unique intervention strategies that are more comprehensive and nuanced.

And, in re-examining our chicken and egg dilemma, our studies indicate that prevention of childhood obesity requires both individual and environmental approaches, working together in a more comprehensive approach.

We agree that childhood obesity is a serious issue. However, this public health challenge is influenced by myriad factors, including genetics, overall diet, and inactivity; not a single source of calories. That said, our industry is doing its part and has taken proactive steps to encourage a healthy balance. For example, our member companies helped lead the way with the implementation of national School Beverage Guidelines, which removed full-calorie soft drinks, cut beverage calories in schools nationwide by 90 percent, and set the stage for the USDA’s new regulations currently underway in schools. We have also led the way on clear calorie labeling so that consumers of all ages can make informed choices. The overarching takeaway? Education that focuses on overall diet and physical activity can help people increasingly embrace healthier habits. This comprehensive approach is capable of changing behaviors in a meaningful and lasting way.

-American Beverage Association

Thank you for your comments and for the opportunity to have a dialogue on this important issue facing our nation (and the international community). As you accurately stated in your post, obesity is influenced by a myriad of factors. This special issue in IJBNPA explores several of these factors, including peer influence and school nutrition policies, and presents an updated childhood obesity framework (Perry, et al.) that we hope will help parents, communities, policy makers, and industry work together to reverse the childhood obesity problem. While education is one important component of how we can help people embrace healthy lifestyles, this special issue makes it clear that, while necessary, a lack of nutrition information or nutrition education on the part of the consumer – and particularly children – is only one piece of a complex puzzle.

We are encouraged by some of the changes that have occurred to the beverage selection available in schools; however, much still remains to be done. While full-calorie soft drinks have been mostly removed from public schools, they have been replaced by alternatives with equal or greater amounts of sugar and/or caffeine. In this way, many states have inched their way forward in school beverage policy reform rather than take the comprehensive steps, recommended by the scientific community, necessary to significantly impact dietary behavior. In fact, as noted by Taber et al., a patchwork approach to sweetened beverage regulation in schools has actually been shown to be counterproductive by shifting rather than reducing the number of calories consumed through sugary drinks.

Parents, communities, policy makers, and industry can and should take proactive steps to encourage a “healthy balance” between diet and physical activity. However, there are certain steps that must be taken if we are to have a truly “comprehensive approach” to meaningful and lasting changes in obesity among youth. Children and adolescents continue to be bombarded by unhealthy food and beverage marketing, and often have easy access to poor dietary choices during the school day. The beverage industry has the power to take a proactive step by removing all high-sugar and caffeinated drinks and eliminating the marketing of those beverages in and around schools and school-sponsored activities. These acts would serve to reinforce and be consistent with the nutrition education and messaging students receive throughout the school day, and would be an important step toward a healthier generation of young people.