Viruses have been the main characters of several pivotal episodes in human history, bringing fear and also fascination to humankind. They represent important forces of population control and natural selection for all living organisms. Before the media was taken over by the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic, others were responsible for the deaths of millions of people just in the past century like smallpox, Spanish flu, and the measles epidemics.

Besides assuaging the ongoing burden of viral diseases, the knowledge of viruses and their environment is a key to improve biology techniques. Viruses help us better understand human evolution and create alternative ways of dealing with other pathogenic microorganisms ‒ like multiresistant bacteria ‒ and the cells they infect. Such information can be used to find cures against other diseases, such as cancer.

Like viruses themselves, virology lectures, the numerous biotechnological applications for these organisms, and the gap between all the knowledge that is generated and how to pass it on to the students is continuously evolving.

This gap is mainly attributed to the fact that the viruses are microscopic organisms, limiting their visualization to schematic figures, illustrations, and electron microscopy. Other problems identified in the teaching of virology are associated with the high cost for ensuring the biosafety of practical classes and motivation and mastery of the subject by the teachers themselves (especially at the high school level).

This gap is mainly attributed to the fact that the viruses are microscopic organisms, limiting their visualization to schematic figures, illustrations, and electron microscopy. Other problems identified in the teaching of virology are associated with the high cost for ensuring the biosafety of practical classes and motivation and mastery of the subject by the teachers themselves (especially at the high school level).

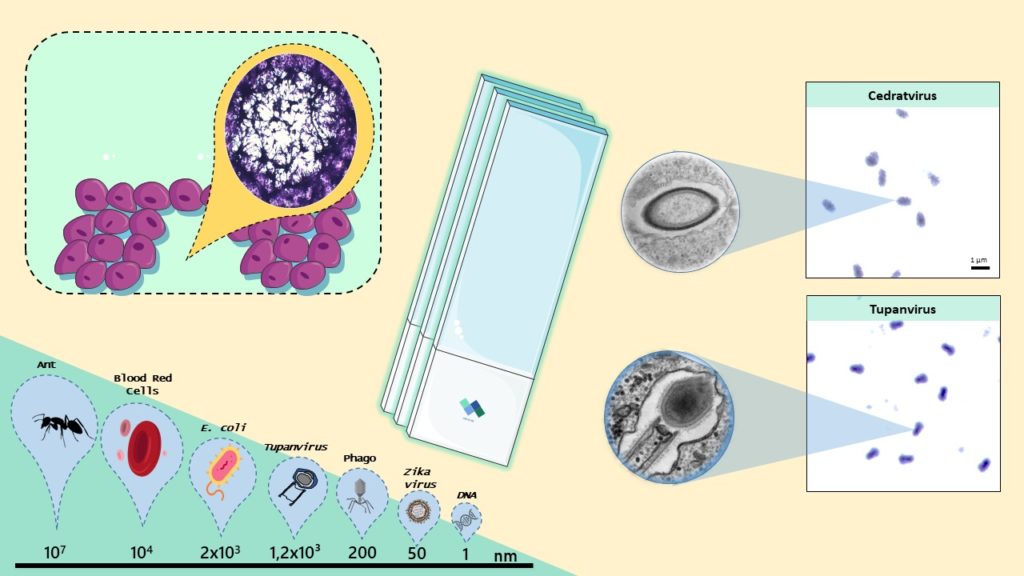

The size limitation, at least, was considered obsolete after the discovery of giant DNA viruses. These viruses typically infect free-living amoebae, having an extensive genome, large particle size, and relative transcriptional independence ‒ breaking several paradigms of classical virology.

However, little has been done to include these new viruses in virology curriculum, which remains outdated and limited mainly to pathogenic organisms, reinforcing the stereotype of viruses as villains.

Developing an educational toolkit

Given all that is known about current virology curricula, a challenge (and opportunity) arose: how to use the fascinating potential of giant viruses to address the challenges identified in virology teaching? What tools could educators be provided so they can expand upon the topics covered and connect them with recent discoveries that would be low in cost?

Thus, the idea was to develop a slide kit for optical microscopy that explores giant virus particles and some aspects of the interaction of animal viruses with cell lines, aiming at an innovative, safe, and low-cost approach to be used in practical classes in the study of viruses.

Using slide staining materials, our viruses stock, and cell lineages, we created a microscope slide kit, which we called “Virus Goes Viral”. It allows the students to observe giant viruses’ particles, viral factories, and the differences between the lysis plaques of other important viruses that infect animals.

In addition to the practical material, the supplementary material was developed in parallel to address one of the earlier noted problems identified in the teaching of virology: lack of mastery of the subject by the teachers. This material is more than a script for practical classes. In addition to suggesting which objective lenses should be used, whether it is necessary to use immersion oil, and what should be observed in each slide, it provides contextualization and definitions for each topic such as: What are viral factories? How are lysis plaques formed? We also made an effort to make the material eye-catching, simple, and interesting to the users.

Testing the toolkit in practice

I had the opportunity to use the slides during my teaching internship program, at the Microbiology department in the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Brazil), where I taught one single practical class for undergraduate pharmacy students.

After contextualizing the discovery of giant viruses, I asked students if they ever imagined that they would be able to see a virus in their lives. I remember them fighting over the microscope where the Tupanvirus slide was, which I had pointed out that it is the biggest virus discovered in the world. I observed the smiles and fascination in their eyes. A student said that for her, it looked just like a bacillus (I had to disagree and draw attention to its unique shape).

Questioning and debating are part of learning and that’s just what we ever aimed for these slides to be: a tool to foster an inspiring learning environment about virology.

Gabriel Augusto Pires de Souza, Victória Queiroz, Erik Reis and Jônatas Abrahão

Victória graduated with a bachelor’s degree in biology from the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais in 2019. Currently working in the Laboratório de Vírus as a Ph.D. student in microbiology at the same university.

Erik has a Bachelor in biomedical sciences (2011), Master in biotechnology (2014) and is temporary professor (2014-2016) at Universidade Federal do Piauí, Brazil. Currently he is a PhD candidate at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais working on arboviruses.

Jônatas is Professor at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Expert in giant viruses, he is head of the Virus Lab-UFMG, Brazil. His main interest is education and discovery of new viruses.

Latest posts by Gabriel Augusto Pires de Souza, Victória Queiroz, Erik Reis and Jônatas Abrahão (see all)

- Virus Goes Viral: An educational kit for virology classes - 20th May 2020

Comments