Autism spectrum disorders affect around 1 in 100 children in the UK. It can be characterized by difficulties in social-interaction and communication, plus a tendency to engage in repetitive behaviors. One common symptom of the disorder is not showing interest in or wanting to play with other children. However, symptoms and their severity vary widely, making diagnosis difficult.

My colleagues and I at UCSD are pursuing a new test to determine whether infants and toddlers as young as one year old are beginning to manifest ASD. During testing, a technique known as eye tracking uses reflection of light from the cornea to map out gaze patterns, while two short videos compete for a child’s attention. One video depicts a favorite topic of typically developing toddlers, other kids at play. The second video depicts a theme more unusual for typical toddlers, geometric shapes and abstract designs.

Toddlers, under 30 months old when they participated, were tracked and evaluated every 6-12 months until they were 3 years old when a final diagnosis was given. At each visit licensed clinical psychologists assessed toddlers using various methods including the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS); as well as obtaining additional family and medical histories.

Across several studies of these Geometric Preference tests, and despite changes to the details of the social and geometric videos presented, an important phenomenon persists. The toddlers who spend the most time viewing the geometric patterns and the least time viewing the social video go on to be diagnosed with ASD. Further, this subset of ASD toddlers are likely to be substantially challenged by the disorder, because they consistently have more severe scores for social communicative deficits and restricted repetitive behaviors than other children with ASD.

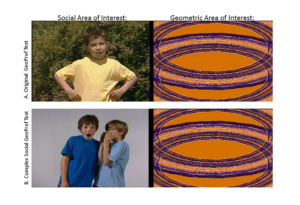

This is the second GeoPref eye tracking test created at our Center, and this particular GeoPref test differs from the original test by the addition of social interactions between multiple children. The original social video shows children energetically moving their bodies in interesting ways, however, the kids depicted aren’t interacting with one another. In contrast, our new social video is focused mainly on kids face to face with one another, speaking together and reacting in ways that nonverbally communicate surprise, or amusement, or agreement, or disagreement.

While evidence shows that early identification and treatment of ASD improves outcomes, the younger the child is, the more difficult it is to say with certainty whether some unusual behaviors mean he or she is on the autism spectrum. Pediatricians see a lot of toddlers who seem to be struggling with something behavioral, but it’s not clear what or why. Because both our GeoPref tests are highly specific, there’s a low chance of false positives, so this tool can add certainty to an uncertain situation.

The original GeoPref test finds with high specificity that toddlers who most strongly prefer these geometric shapes have ASD. But the original test can’t rule out ASD, because some toddlers with ASD do watch the video of kids in motion. Unexpectedly, for the new test not only were all the kids with the highest scores ASD, none of the kids with the lowest scores were ASD. This means the new test can not only identify infants with ASD, but also rule-out ASD risk in some kids who may have concerning behaviors.

In this study we were also happy to find that by combining multiple GeoPref tests, we were able to identify additional toddlers with ASD, that is, two GeoPref tests were more sensitive than one. Our next step is to design a series of eye tracking tests like this one that when combined will maintain the high specificity we’ve achieved, while increasing the sensitivity. We want to be able to ensure we continue to detect severely impacted kids with our tests, whilst also being able to identify those children that are less severely impacted, but nonetheless do fall somewhere on the autism spectrum.

Comments