The world’s herbaria hold millions of samples of plants, and until recently they have been largely the domain of taxonomists – those scientists who describe diversity. Herbarium taxonomists compare specimens collected in different parts of the world, assess variation and then come to conclusions about what to name as new, and what to call the same. Our ability to talk about plant diversity depends upon this activity – without names, we would be unable to tell each other about distribution – and as so alarmingly today, decline – of the some half a million plant species with which we share the planet.

A herbarium can be considered a physical database – each plant specimen is a data point.

Herbaria though are often depicted as dry, dusty out-of-date places, not really connected to the dynamic world of today’s societal needs. But actually, a herbarium can be considered a physical database – each plant specimen is a data point – something that occurred somewhere, sometime, with a particular combination of traits. In a study recently published in BMC Biology, Marc Sosef and colleagues show how powerful a resource these herbarium collections can really be, even in the underexplored tropical rainforests.

The data

Using the RAINBIO dataset – a collaborative, curated (more about that later) database of herbarium specimens from many institutions all collected in tropical Africa – they perform a number of analyses exploring African plant diversity. Heterogenous datasets like these assembled from herbarium specimens – whose collection is by its very nature ad hoc – are sometimes considered to be less than useful for generating solid estimates of things like species richness, rarity, or turnover (but see commentary in BMC Biology). But for many environments, these are all the data we have.

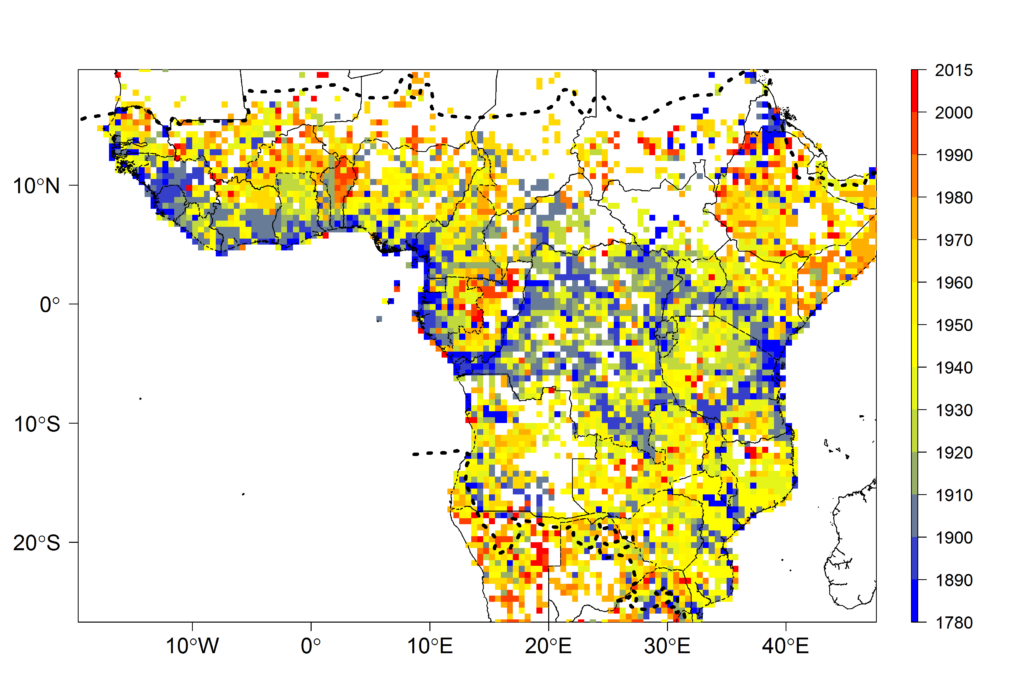

Specimens in the RAINBIO dataset date from 1782 to the present – almost 250 years of data collection. Figure 5 in the paper graphically shows how exploration of Africa unfolded, along the rivers, tragically along the west coast in association with the iniquitous trade in enslaved people, and patchily through colonial activity in the early part of the 20th century. The history of European engagement with Africa unfolding along with the plants sent to collections, first in European and later also African institutions, is a reminder that science is part of society and does not develop outside of it.

The robustness of the conclusions drawn by Sosef and colleagues is highly dependent upon the curational state of the data themselves. Taxonomic verification of the identities of samples held in RAINBIO dataset is key to this – this requires taxonomists. One of the things that most impressed me about this study was the degree to which data were validated by taxonomic experts – those scientists whose knowledge of whether or not two names in a list represent the same thing or different species, or whether a species described as a tree on a specimen label really is a tree. There have been criticisms of data served through the GBIF network, for example, but such data are only as good as the curation effort expended; to make use of these rich data sources, first catch some taxonomists and have them on the team!

The findings

The functional data analyzed from the RAINBIO dataset is novel and reveals really interesting patterns. The authors show that the proportion of herbaceous to woody plants is at the upper suggested limit (just under half, 44%). This says to me that tropical botanists need to focus on this vegetation layer as well as on those sexy big trees. An interesting comparison would be of rarity of herbaceous versus woody components of tropical vegetation. If Begonia species are anything to go by, herbs can be extremely rare and range restricted indeed!

The authors use the patterns revealed by their analysis to suggest collecting priorities for tropical Africa.

Shockingly, the average number of collections per 0.5° square in Africa is 1.84 – that is fewer than two plant records in a square 55 kilometers on each side. Some places, of course, are better collected than others, but let’s get out there! The authors use the patterns revealed by their analysis to suggest collecting priorities for tropical Africa – they identify Tanzania, Atlantic Central Africa and West Africa as priority areas for further collecting to increase our knowledge of plant diversity.

But I might argue that looking at Figure 5, we should seriously think about increasing collecting effort at the northern edge of the African tropics – after all, that is the leading edge of climate change and the area where effects will be felt soon as the environment degrades. These aren’t the big rainforests, but these habitats and areas can be canaries for climate change.

Herbaria (and other natural history collections) represent big science – they are the CERN of natural history. These resources represent an unparalleled infrastructure for looking at how plant diversity is distributed, and are our best hope for documenting how it is changing at a global scale. Imagine if governments or private foundations invested in the digitization of all these invaluable resources, pretty straightforward for flat 2D objects like herbarium sheets, more difficult for 3D objects like insects or worms. The infrastructure thus created, especially if investment is also made in its careful curation and verification, would be the most powerful picture, however flawed it might be, of the Earth’s diversity before it is lost forever. We are crazy not to pull together to create this infrastructure to help us predict our plant’s fate.

Comments