Science is hard. If you’ve spent a stint in a biomedical research laboratory you’ll almost certainly have learned this lesson the hard way. Perhaps you felt it first when you set up an experiment for the nth time thinking that the tweak you did to the protocol will do the trick. You’ve read the literature carefully, made up reagents afresh, tried to be rigorous in your thinking, discussed it with colleagues, planned your controls.

But a lingering doubt remains because this is exactly what you told yourself last time. Maybe the experiment is failing or the result makes no sense, because it’s based on a false assumption, or because you’re using the wrong system to test your idea? Or maybe the experiment isn’t working for some stupid little reason – maybe it’s the water or the lids on the coloured Eppendorf tubes? Maybe everything will become clear in a flash of inspiration in the middle of the night? Maybe you’ll be lucky this time?

Eventually, though, if you are persistent, smart, flexible in your thinking, read the literature and get help where help is needed, you begin to see that its possible to make steady progress. An experiment might start to work because you cracked an essential problem, or because you optimised a multiplicity of minor issues, because you tried something else, or without you ever even discovering the reason. Or a control experiment might reveal something entirely unexpected.

Watson and Crick had plenty of false starts along the way

The lesson becomes clear. Rigor, clear thinking, and wielding a pipette with precision aren’t enough. Doing science requires tenacity. Watson and Crick had plenty of false starts along the way. To succeed, you must really want to know the answer to your question. And, like a rock-climber, you need to get satisfaction from finding a good new foothold. Not just when surveying the view from the top.

It’s a common experience. But it isn’t the impression you are likely to get as a student sitting through a research talk. When a charismatic key note speaker takes to the podium at an international meeting, the story she or he is telling is likely to be one they have told dozens of times before: one they have woven out the fabric of the successive failures and successes of a team of hardworking students and post-docs over many, many years; some of whom, through bad luck or lack of persistence, have fallen by the wayside; some of whom have made it; almost all of whom have now left the lab.

Once the data make it up onto the wide screen, the sweat and blood have been washed away: what remains is a story. This is what we call science. But it’s the cinematic epic version. No one bothers to screen the “making of”. Similarly, the difficulties involved in doing science aren’t communicated to the reader in papers published in brief in widely read journals. In a ‘well written paper’ everything unfolds as it should. Hypotheses are framed and then tested.

No one bothers to screen the “making of”

In fact, it’s very for a rare journal to agree to publish a novel hypothesis without, at the same time, publishing the data that put it to the test – even though, as a consequence, one can’t tell if a model predicts or explains the data. And data presented without a framing hypothesis is called ‘descriptive’ – a designation that can be used to kill the chances of its being published.

It makes some sense to present things in this way, but it’s a strange way to describe what we do. By making the communication of new facts, ideas and impact the focus of what we present to the world, we conceal the day to day realities of the process by which we uncover new things about the world in which we live.

In fact, although the difficulties of publishing often loom large, they pale in comparison with the difficulties of discovering something really new. It is nature, not publication, that scientists grapple with day and night. This is why the delays and traumas associated with publishing our small hard won discoveries feel so damn frustrating.

It is nature, not publication, that scientists grapple with

It’s the struggle along the way that truly is the scientific method. It is the failed experiments, ambiguous data, tears and fallen ideas, not the statistical tests, upon which our understanding of the world rests. This is why no-one can dismiss what scientists do as biased, fake or elitist. Almost anyone can do it; but it’s hard.

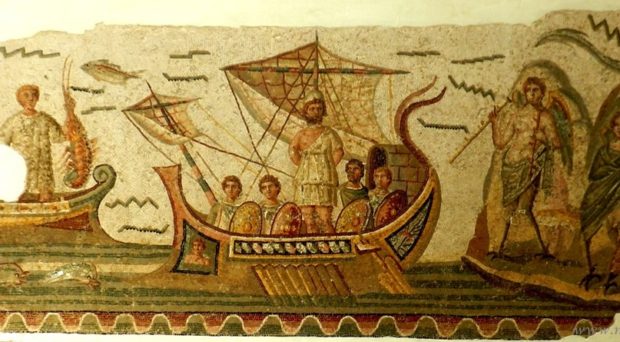

Perhaps it’s time for scientists to celebrate this secret truth at meetings, when training the next generation of scientists, and in our discourse with the public. It is the Odyssey, not the conquest, that makes science a heroic pursuit.

And by recognising this, perhaps we can lessen the unrealistic pressure put on young researchers to quickly come up with and publish startling new hypotheses and the data to support it; freeing the determined and insatiably curious to enjoy the long, hard and meandering path through nature’s beautiful landscape in search of the way things actually work.

Benjamin (Buzz) Baum

Latest posts by Benjamin (Buzz) Baum (see all)

- Science: A journey in search of a destination - 22nd February 2017

Peter Medawar pointed out a long time ago that the way science was presented didn’t reflect the actual process. That would be less important if the results were reliable. What Medawar didn’t know about was the crisis in reproducibility. I guess it just isn’t known whether science has become less reproducible since his time.

Irreproducibility was discussed this morning on the Today prodramme. It is public knowledge and it’s doing great harm to the reputation of science. I suspect that part of the reason is misunderstanding of statistics -the tyranny of P = 0.05 has done huge harm. It’s very rare to meet a working scientist who understands what a P value tells you -the most common answer is that it’s the probablity that your results occurred by chance. It isn’t.

The other reason is the insane pressure to publish every 10 minutes. This is largely the fault of senior scientists and of politicians who imposed on us the REF. People should be rewarded for publishing fewer, more complete and more careful papers. I’ve suggested that people should be allowed to publish no more that one or two papers a year. And that the size of labs should be limited to ensure proper supervision. One of the more satisfying experiences of my life was seeing a candidate for Fellowship of the Royal Society rejected on the grounds that they had published so many papers that they’d barely have been able to read all the things that came out with their name on it.

It worries me that I now feel obliged to apologise to young scientists for the regime that my generation has imposed on them.

A very insightful comment. And I couldn’t agree more, particularly regarding the toxic REF.

Very well put. If I may be allowed a small quibble; having done both lab and field work I can testify that the stresses of scientific research are not confined to the laboratory. Out in the field the the frustrations multiply simply because nothing is ever really under control. At least in a lab you are warm and dry, and everyone recognizes that you are working. If you do field work an astonishing number of people treat you as if you are on holiday.