Human sparganosis

Human sparganosis is a neglected food-borne parasitic disease caused by the larval forms of tapeworm species in the genus Spirometra. A recent review concluded that there were 4 valid species (S. erinaceieuropaei, S. mansonoides, S. pretoriensis and S. theileri) in the genus Spirometra; however, dozens of nominal species of Spirometra have been described. Although the disease has a global distribution, most cases occur in Eastern and South eastern Asia.

Adult tapeworms in the genus Spirometra live in the intestines of dogs and cats. The infection is spread when eggs are shed in feces. The eggs embryonate and hatch in water to release coracidia, which are ingested by copepods. Within the copepod intermediate host, the coracidia develop into procercoid larvae. Second intermediate hosts, such as fish, reptiles and amphibians, ingest infected copepods and the procercoid larvae develop into plerocercoid larvae (spargana). The life cycle is completed when a predator (dog or cat) eats an infected second intermediate host.

Humans can become accidentally infected by either drinking water contaminated with infected copepods or consuming the flesh of an under-cooked second intermediate or paratenic host. Humans serve as a paratenic or second intermediate host and develop sparganosis. Spargana can live up to 20 years in humans.

Clinical presentation

Spargana may locate anywhere within the host, including subcutaneous tissue, breast, orbit, urinary tract, pleural cavity, lungs, abdominal viscera and the central nervous system.

Migration in subcutaneous tissues is usually painless, but spargana in the brain or spine can cause a variety of neurological symptoms. Inner ear involvement may cause vertigo or deafness in the host. On rare occasions, Sparganum proliferum can cause proliferative lesions in the infected tissue, with multiple plerocercoids present in a single site.

The sparganosis situation in China

In China, frogs play an important role in the spread of sparganosis. Humans can be infected through the consumption of raw or undercooked frog meat or by using raw frog flesh in traditional poultices. Investigating spargana in frogs is therefore essential for the prevention and control of human sparganosis.

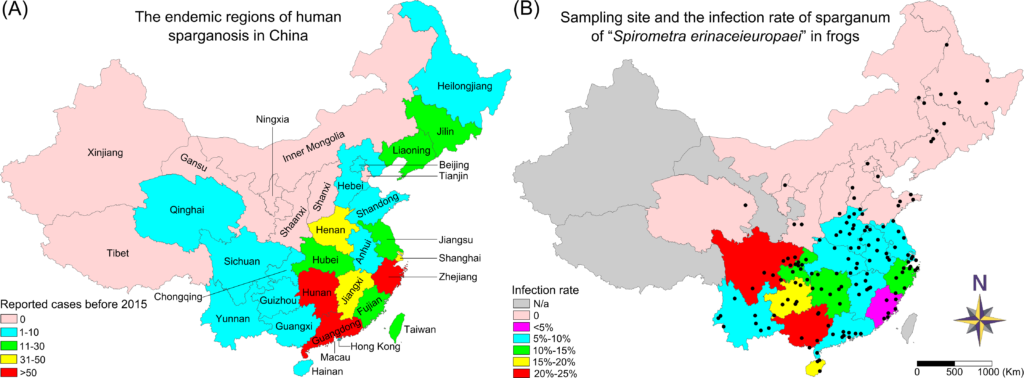

The number of reported cases of human sparganosis in China has exceeded 1300 but may be far higher as many cases may not be recognized or reported. Human sparganosis has been reported in 26 of 34 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities in China, with the majority of cases in Southern and Eastern China. However, there is a lack of data on the geographical distribution of sparganum infection in wild frogs in all regions of China where the parasite is endemic.

In light of this, a recent study conducted the first large-scale survey of sparganum infection in wild frogs from 145 geographical locations that covered 88.9% of the endemic regions of human sparganosis. The study aimed to identify the collected sparganum specimens using molecular identification.

Prevalence and type of sparganum infection in frogs in China

From July 2013 to September 2018, sparganum infection in wild frogs was surveyed at 145 geographical locations from 28 of the 34 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities in China. A total of 4665 wild frogs belonging to 13 species were collected in paddy fields or other wild environments and euthanized.

Collected sparganum isolates from the different locations were subjected to molecular identification by a multiplex PCR assay and analysed by cluster analysis. For each specific locality, one sparganum was selected for PCR analysis.

Infected frogs were identified in 80 of the 145 surveyed locations. Sparganum infection rates in wild frogs in several regions of China were still high (above 10%), especially in South and Southwest China. Sparganum infection was found in 8 out of 13 frog species. The most frequently infected species was Pelophylax nigromaculatus (infection rate was up to 14.07%).

Sparganum infection prevalence in wild frogs ranged from 0 to 66.67%, with an infection intensity of 1–49 spargana per frog in different geographical locations. Most of the spargana were present in the thigh muscles of the frogs.

Seventy-two spargana were sampled for molecular identification. Cluster analysis showed that sequences from the Chinese isolates were very similar to those identified as from S. erinaceieuropaei. However, more morphological and molecular phylogenetic analyses are necessary to clarify the taxonomy of the genus.

Conclusions

The survey by Zhang and colleagues found that 8 frog species were sensitive to sparganum infection. The sparganum infection rates in wild frogs in several regions of China were still high, especially in South and Southwest China. Eating wild and improperly cooked frogs in China is associated with considerable health risks. Several traditional Chinese folk remedies may also increase the risk of infection. The sparganum isolates in China are most likely from S. erinaceieuropaei, but new studies, especially comprehensive morphological analyses, are needed.

Comments