Trachoma is the leading cause of preventable blindness, causing blindness or visual impairment in around 1.9 million people worldwide. Despite this stark statistic, significant progress has been made in the fight against the debilitating and disfiguring bacterial infection. It has been 25 years since the WHO first adopted the SAFE strategy to prevent and treat trachoma. To support implementation of the SAFE strategy by Member States and reinforce national capacity, the WHO launched the WHO Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020 (GET2020) in 1996. It has now been over 20 years since the World Health Assembly set this ambitious target to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem by 2020 (resolution WHA 51.11). With the deadline fast approaching, we look at what has been achieved so far.

Trachoma in 2018

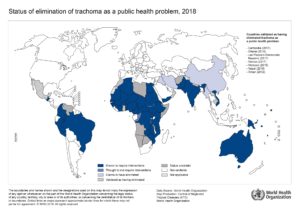

Currently, there are 43 countries known to require interventions for trachoma, and the disease is hyperendemic in many impoverished and hard-to-reach areas of Africa, Asia, Australia, Central and South America, and the Middle East. Africa is the most affected, with 27 countries known to require interventions for trachoma. In 2016, a reported 190.2 million people lived in trachoma-endemic areas and are at risk of blindness. On top of the devastating clinical manifestations of the disease, the loss of productivity is estimated to cost US$ 2.9–5.3 billion annually, and up to US$ 8 billion when trichiasis (inward direction of the eyelashes) is also taken into account.

The disease

Trachoma is caused by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, an obligate intracellular bacterium. The infection is spread when people are exposed to eye or nose discharge from infected people, such as through hands, clothes or bedding, or by flies. Young children are the main infection reservoir, and active (inflammatory) trachoma is common among preschool-aged children in endemic areas.

Trachoma is classified by five clinical grades.

Progression to the more severe stages of the disease is due to repeated infections over several years, where recurrent inflammatory episodes can eventually cause the upper eyelid to turn inwards. This stage is known as trachomatous trichiasis and is a result of the eyelashes rubbing on the eye, causing scarring and pain. If this stage is not managed with surgery, it will progress to the corneal opacity stage, where a person is irreversibly blinded.

The time it takes to develop blindness from trachoma is linked to the community infection intensity, but typically occurs in people aged between 30 and 40 years of age. Blindness is also 2 to 3 times more common in women than in men, likely due to more frequent contact with infected children.

The strategy

Working towards the sustainable control and elimination of trachoma by 2020, the WHO recommends an integrated approach using a combination of four main interventions, with national implementation supported by the WHOs GET2020 partnership. The strategy is known as the ‘SAFE strategy’, and consists of:

- Surgery to treat trachomatous trichiasis and prevent blindness;

- Antibiotics to treat infection, particularly large-scale treatment of endemic areas;

- Facial cleanliness to reduce transmission; and

- Environmental improvement, particularly improving access to water and sanitation.

Surgery for trichiasis is required to return the eyelid to the normal position.

To ensure people who need surgery have access to it, volunteers in the community are trained to be ‘trichiasis case finders’. These people are responsible for finding trichiasis cases and referring suspected patients to the trichiasis camps for verification and surgery.

To help prevent trachoma developing to more advanced stages requiring surgery, the WHO recommends annual mass drug administration (MDA) with antibiotics to all endemic areas at risk, known as ‘preventive chemotherapy’. Preventive chemotherapy is provided to reduce morbidity and prevent transmission. Azithromycin (Zithromax) is an antibiotic that has been freely donated by Pzifer for trachoma since 1999.

For the F & E components of the SAFE strategy, improvements in accessible water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) are required as poor hygiene and dirty environmental conditions enable ongoing transmission. The main environmental intervention is promoting methods to hygienically dispose of human faeces, as the female Musca sorbens flies which can transmit C. trachomatis preferentially lay their eggs on human waste. The WHO also supply facial kits, consisting of a face towel and soap, to promote hygiene and facial cleanliness.

Trachoma elimination – Success stories so far

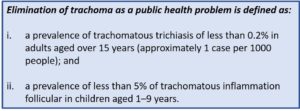

Major strides have been made towards meeting the ambitious targets set out in resolution WHA 51.11, and 11 countries have so far reported meeting the elimination goals.

This includes: Cambodia, China, Gambia, Ghana, Islamic Republic of Iran, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Mexico, Morocco, Myanmar, Oman and Nepal. Seven of these countries – Mexico, Morocco, Oman, Lao’s Democratic Republic, Cambodia, Nepal and Ghana – have since had their elimination status validated by WHO. Nepal is the first country in South-East Asia and Ghana the first country in the WHO’s African Region to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem.

In 2016 alone, over 260 000 people received surgical treatment for trichiasis and 85 million people received treatment. Global coverage with antibiotics had also increased to 44.8% in 2018 from the 29.6% coverage achieved in 2015, showing efforts are indeed accelerating. Other successes include the launch of Yemen’s first large-scale treatment campaign targeting around 450 000 people in May 2018, despite continuing civil unrest and instability.

The future for trachoma?

Trachoma elimination is an ongoing success story, however there is still much progress to be made. In 2016, the WHOs GET2020 published its action plan, ‘Eliminating Trachoma: Accelerating Towards 2020’, describing what must be done to scale up trachoma initiatives. To drive elimination efforts forward will require improving coverage, enhancing intervention strategies, linking multiple sectors, and obtaining the necessary funds. Through consolidated efforts and collaborations with policy makers, funders, implementing partners, and those affected, global elimination of trachoma as a public health problem will hopefully be a reality in the near future.

2 Comments