The outbreak

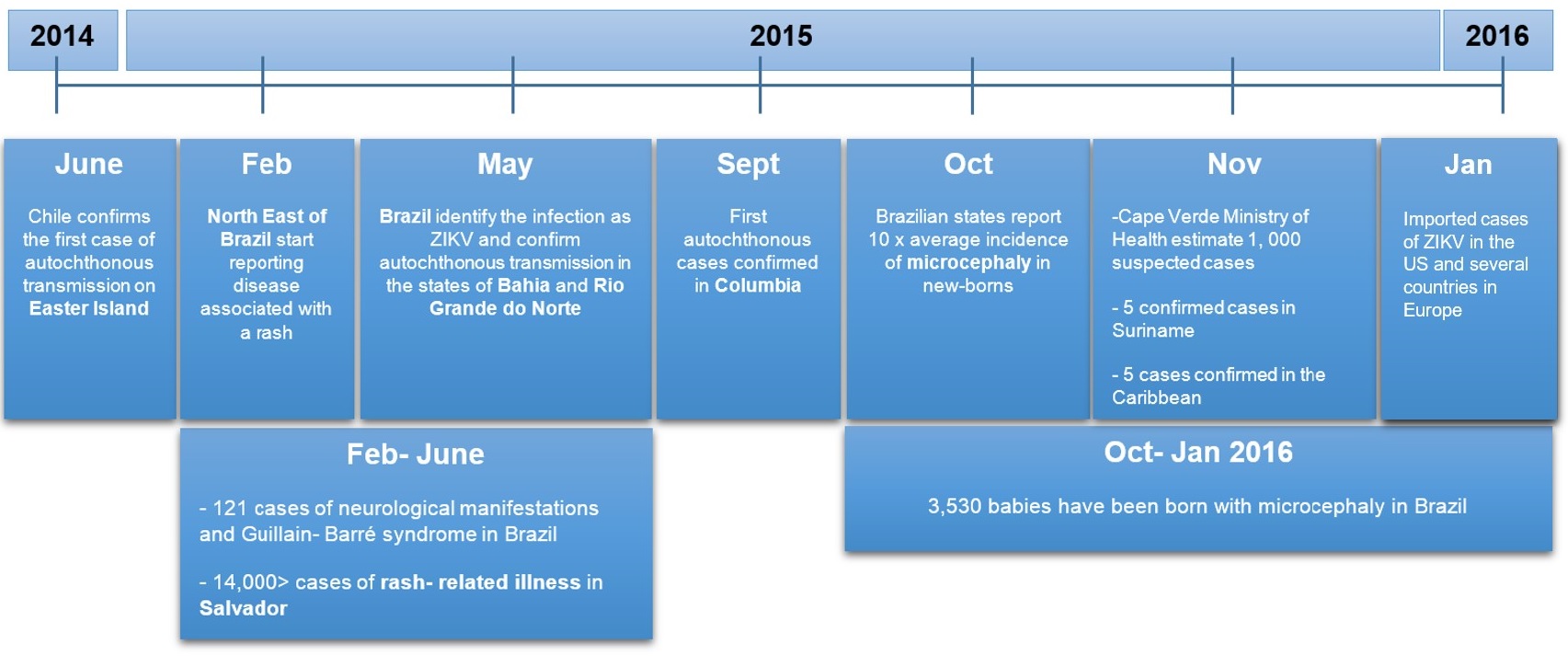

The first confirmed case of transmission of ZIKV infection in the Americas was reported from Easter Island, off the coast of Chile in June 2014. Around February 2015, states in the North East of Brazil began reporting a disease associated with a rash.

Over 14,000 cases of rash-related illness were reported in Salvador, Brazil between Feb-June 2015. In May 2015, Brazil identified the infection as due to virus Zika and confirm autochthonous transmission (the spread of infection from one individual to another in the same area) in the states of Bahia and Rio Grande do Norte.

During October 2015, health officials across several states described a ten-fold increase in the incidence of microcephaly in newborns. Since then, 3,817 babies have been born with microcephaly, where the yearly average was 150- 200 cases. Curiously, 121 cases of individuals with neurological manifestations and Guillain- Barré syndrome were also reported, a rare condition that had been reported when ZIKV transmission extended to South East Asia.

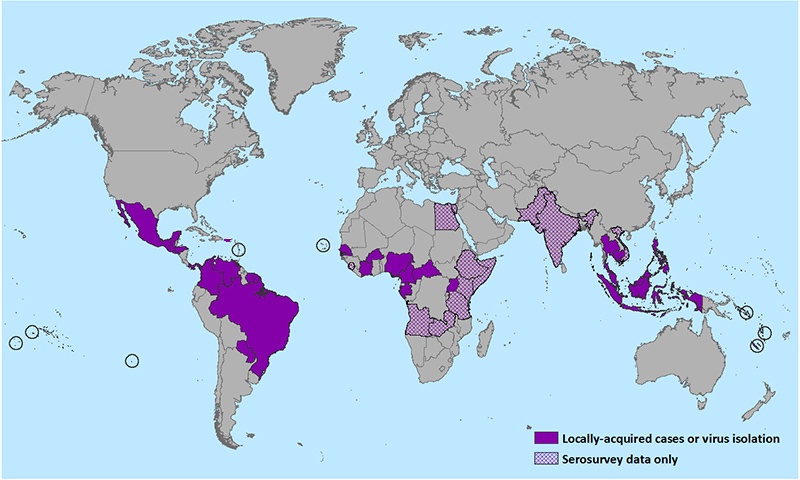

The virus has spread throughout most of South America and some countries in the Caribbean. Several cases have been identified in the United States, although all (except Puerto Rico) have occurred in travelers returning from infected areas.

Previous Outbreaks

Outbreaks have occurred in parts of Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands. In 2007, during an outbreak on Yap Island (Federal States of Micronesia) 73% of Yap residents aged 3 yrs or older were estimated to have recently been infected with ZIKV.

Although there were no hospitalisations nor deaths, rashes, fevers, arthralgia and conjunctivitis were widespread. Phylogenetic analysis of serum samples collected in Bahia, Brazil showed the ZIKV strains belonged to the Asian lineage and showed 99% identity with a sequence from a ZIKV isolate from French Polynesia.

The potential for autochthonous transmission in countries where Aedes vectors are present is evident and cause for concern given the speed at which the disease has spread.

The virus and the disease

First discovered in the Ugandan Zika forest, the ZIKV is a member of the Flaviviridae family, closely related to dengue, Yellow fever and West Nile viruses. It is similarly transmitted through the infectious bite of an Aedes mosquito, mainly A. agypti and A. albopictus. A. hensilii has also been suggested as a possible vector of ZIKV after it was found to be the most abundant species during an outbreak on Yap Island in 2007.

The symptoms of Zika disease manifest within a week of being bitten by an infected mosquito; these include fever, muscle and joint pain, headache, nausea, and rash. These non-specific symptoms can often lead to a misdiagnosis of dengue or Chikungunya.

Although symptoms only develop in 20% of cases, it can be lethal. Since the start of 2016, 46 deaths associated with Zika have been recorded. Diagnosis of ZIKV can be confirmed by RT-PCR within the first week of infection, although the test is only available in reference laboratories. Currently, there is no vaccine nor treatment for ZIKV.

Neurological complications

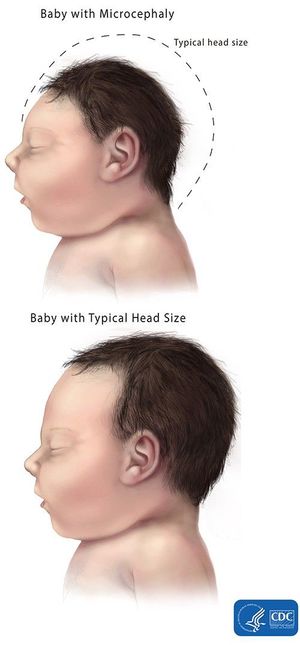

Since the start of the 2015 outbreak in Brazil, the incidence of microcephaly among newborns has increased twenty-fold in the North-Eastern states of Brazil. Microcephaly is defined as an abnormally small head circumference in relation to the size of the child and duration of pregnancy.

The relationship between microcephaly and Zika disease is unclear. It is especially complicated as microcephaly can be caused by several other factors including genetic abnormalities, exposure to toxic substances and exposure to other infectious disease such as toxoplasmosis during pregnancy.

Also, many of the afflicted babies have tested negative for ZIKV. However, the temporal and geographical coincidence between the start of the outbreak and the 6-month delay before microcephaly reporting is in line with the development of microcephaly due to an infectious disease. Similarly, the incidence of the autoimmune disease Guillain-Barré syndrome peaked during the previous and current outbreaks.

However, this association is still based on ecological evidence and more research is needed. The European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) conclude “a causative association between microcephaly in new-borns and ZIKV infection during pregnancy is plausible, but not enough evidence is available yet to confirm or refute it”.

Travel guidelines and governance

The CDC has just released guidelines for pregnant women travelling to or returning from areas of the Zika outbreak. Pregnant women should re-consider travelling to areas with on-going transmission, if they do travel they should avoid mosquito bites by wearing long sleeves/pants, repellent and staying in screened houses with air-conditioning.

Health professionals have been advised to screen pregnant women with a history of travel to areas of transmission, they should also be screened for dengue and chikungunya in accordance with existing guidelines. A positive RT-PCR diagnosis using maternal serum confirms ZIKV in the mother, however the baby can only be tested for ZIKV by amniocentesis, a test that carries its own risks.

The CDC are currently developing guidelines for infants born with the disease. Overall, anyone traveling to Brazil and other areas in Latin America, should take precautions to avoid mosquito bites vector to reduce their risk of infection with Zika virus and other mosquito-borne viruses such as dengue and chikungunya.

The Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) and World Health Organisation (WHO) have recommended to their member states, particularly where potential vectors are prevalent, to enhance vigilance towards the detection of imported cases of ZIKV infection.

This includes increasing awareness of health professionals, especially those involved in prenatal care in endemic areas, but also in countries receiving travellers. Presentation of a maculopapular rash with or without fever in travellers returning from ZIKV outbreak areas should be investigated as potential cases. The ECDC is also working to strengthen laboratory capacity to confirm suspected ZIKV infections and rule-out other arboviral infections.

Professor Luis Cuevas at the LSTM comments, “Our perception of Zika has changed from being a relatively innocuous infection rarely causing complications to an emergent public health problem in South America. This outbreak has demonstrated that surveillance data is difficult to interpret if we don’t have suitable diagnostics.

We need better diagnostics for arboviruses that are easy to use and close to the patient. This is especially true for dengue, chikungunya and Zika, which are causing overlapping epidemics in Brazil.”

Thank you for a clear and informative piece on such a current topic