As part of collaborative study between teams working at Lancaster University in the UK, IOC-FIOCRUZ and UFPI in Brazil, we have shown that sand flies carrying Leishmania are able to survive attack by a bacterial pathogen that would have otherwise killed the insect. This suggests that Leishmania benefits its insect host whilst increasing the chances for its own transmission.

Leishmaniasis is a Neglected Tropical Disease caused by protozoan parasites of the Leishmania genus and transmitted from mammal to mammal through infected sand flies. According to the WHO, 1.3 million people become infected with the parasite each year, with 20 – 30 000 people dying as a result. It is therefore crucial to eliminate the disease, and help to achieve this we need to learn more about the parasite, the vector and how they interact.

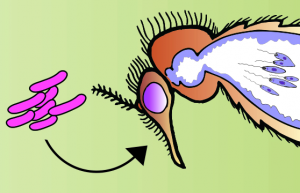

The three way relationship between insect, parasite and mammal in the wild must be set against an environment where both insect and parasite are constantly in competition with other forms of microbial life that may kill both the insect and parasite. Adult sand flies are thought to live for only 10 days or so in the wild. During that time, the sand fly must feed on a Leishmania-infected mammal to pick up the parasite – which then colonises the gut – and stay healthy for long enough to transfer Leishmania to the next mammal via regurgitation during the blood feed.

It is well established that exposure of insect vectors of disease to insect pathogens can interfere with the transmission of medically important parasites. We have also shown in our study that insect gut microbes may prevent the transmission of a parasite by directly competing with the parasite or activating the insect immune system. But the idea that an insect vector carrying a medically important parasite might be protected from insect pathogens by the parasite itself does not seem to have been considered. To test this idea we used a sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis, the main vector of Leishmania causing the deadly visceral leishmaniasis in the Americas and a bacterial pathogen, Serratia marcescens – a species previously found associated with wild Lu. longipalpis that is also lethal to Leishmania in vitro.

When we investigated the effect of infecting sand flies with both the pathogen and the parasite, sand flies that were already infected with Serratia and subsequently fed with Leishmania showed a significant reduction of the Leishmania population in the gut, reducing the potential for transmission of the parasite to a mammalian host. Furthermore, sand flies that already carried Leishmania were then fed with the insect pathogen and flies survived significantly longer than flies without the Leishmania in their gut.

There is little evidence to suggest effects of Leishmania on the fitness of the sand fly host and there was no difference in survival of flies with Leishmania infection without the Serratia challenge during the period of the experiment. Leishmania populations in the sand flies subsequently fed Serratia were maintained at similar levels as control insects, suggesting that the association between Leishmania and its insect vector helps maintain the parasite population in contrast to the scenario suggested by the in vitro experiment where Leishmania are killed.

This work suggests that the association between the sand fly Lu. longipalpis and the Leishmania can be mutually beneficial. Extending the lifespan of sand flies by just a few days in disease endemic areas may greatly promote Leishmania transmission and contribute to the successful spread of the disease. A final implication is that developing biological control campaigns against insect vectors of disease using either naturally derived or genetically modified insect microbial pathogens may have unexpected effects in the wild. Perhaps in an extreme case we may end up with sand fly populations where an increased proportion of the survivors was carrying the human disease agent that the campaign was trying to eradicate.

——————————

This work is part of an ongoing collaboration by Dr Rod Dillon’s sand fly research group, Prof Paul Bates Leishmania group in the Faculty of Health and Medicine at Lancaster University UK, Dr Viv Dillon at Liverpool University, Dr Mauricio Sant’Anna at the University of Minas Gerais in Belo Horizonte, Dr Fernando Genta’s group in Brazils leading public health research institute IOC-Fiocruz based in Rio de Janeiro and Prof Cavalcante in Teresina, NE Brazil (UFPI). Dr Dillon is also funded by the Brazilian Science without Borders program to continue this collaborative work to develop new approaches to reduce cases of leishmaniasis in Brazil by disrupting parasite transmission by the sand fly.

One Comment