Menstruation in a Refugee Settlement

In humanitarian settings, individuals who menstruate face numerous obstacles in managing their menstrual health (MH). The barriers are profound, including scarcity of sanitary materials, washing supplies, and safe, private spaces for changing and disposal.

Despite a growing commitment from the humanitarian field to address MH through the introduction of new guidelines, research, and programming, the solutions introduced to combat these challenges have often fallen short. They are implemented across diverse humanitarian settings without sufficient tailoring to address unique contextual nuances, such as geographical factors, existing infrastructure, and cultural beliefs surrounding menstruation. Most importantly, the voices of those directly affected — residents of humanitarian spaces, particularly individuals who menstruate — are rarely included in the design and development processes.

A Human-Centered Design Approach

In collaboration with Alight, a non-profit organization in the humanitarian sector, and Kuja Kuja, a global data collection firm, our team at YLabs, a global design and research organization, set out to develop a Human-Centered Design (HCD) solution with and for individuals who menstruate in the Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement in Northern Uganda in 2020.

HCD is an approach that prioritizes the needs, perspectives, and experiences of end beneficiaries, and uses a creative and participatory process in co-designing, developing, and testing potential solutions. In our case, this meant deeply involving individuals who menstruate and other community stakeholders, allowing them to lead on key decision-making points.

One of the processes used to ensure that end beneficiaries are highly involved in the development of solutions is called co-design. Co-design is grounded in the belief that all people are creative and, as experts of their own experiences, bring different points of view that inform design and innovation direction. During the co-design process, we used various participatory activities such as card sorting, journey mapping, and role playing to gain deeper insights and challenge assumptions about our potential solutions. Overall, we conducted over 340 interviews, focus group discussions, and working sessions to ensure we were building something that was addressing the primary needs of individuals who menstruate.

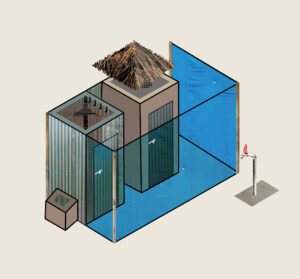

In total, four concepts were tested to assess their desirability, cultural acceptability, and feasibility. Among these interventions, the Cocoon Mini emerged as the most promising concept. The Cocoon Mini is a secure and private MH management-dedicated space that offers access to a personal latrine, a bathing facility, and waste disposal options. Based on its potential, we advanced the Mini into a three-month pilot program.

From Co-Design to Design Principles

Throughout the research, co-design, and prototyping phases, we created four design principles and a set of tips for how to design MH spaces in humanitarian settings at scale.

- Ensuring physical and physiological safety among individuals who menstruate is more important than the MH space itself.

- During prototyping of the Cocoon Mini, individuals who menstruate raised concerns about the potential risks of abuse, both physically and psychologically, that they might face from men and boys. They shared that when public spaces are explicitly designated for MH, they can draw unwanted attention. To address this, we worked together with young people to redesign existing latrines, prioritizing safety and user-friendliness.

- Tips to ensure safety at scale: Maximize privacy in every MH space to ensure user safety and discretion. Incorporate essential elements like tall privacy walls, robust doors with secure locks, interior lights, clearly-lit pathways to the structure, and lockable disposal bins.

- Spaces should cater to every stage of the menstrual management journey, addressing the comprehensive needs of individuals who menstruate.

- Individuals who menstruate highlighted that current solutions tend to prioritize one aspect of menstrual health management, such as the distribution of sanitary materials. Through a collaborative brainstorming session, we identified the essential features and components necessary for a comprehensive approach that covers all stages of menstrual management, including changing, bathing, washing, and proper disposal of products.

- Tips for comprehensiveness at scale: Build spaces that integrate bathing shelters equipped with hooks, shelves, and a platform for bathing and laundering, a water source tap, and a disposal bin with a lock and an attached incinerator to ensure the complete destruction of products.

- The value of a MH space will be measured by its material longevity.

- Temporary or makeshift structures are prevalent in humanitarian settlements and are prone to rapid degradation. Through co-design, we learned that individuals who menstruate highly value and desire spaces that are durable, long-lasting, and seen as permanent in the community.

- Tips for durability at scale: When possible, prioritize the use of robust materials like iron sheets for privacy walls, treated timber to protect against termites and rot, and bricks with enhanced mineral composition and stronger aggregate. Additionally, consider incorporating timber and mesh reinforcements for latrine pits to ensure long-term durability.

- Community ownership fosters the long-term sustainability of MH spaces

- During the co-design process, community ownership and responsibility emerged as a crucial aspect for ensuring the sustainability and acceptance of a Cocoon Mini from local stakeholders.

- Tips for sustainability at scale: Involve local masons and community members in the construction and maintenance of the Mini spaces. This approach not only strengthens the sense of ownership, but also improves the longevity of the spaces and develops local expertise for future construction projects.

Piloting the Cocoon Mini

During the pilot phase, 20 Cocoon Minis were built within individual compounds in the settlement, each assigned a supervisor from the household for maintenance purposes. Overall, the 20 Cocoon Minis served an estimated 300 people, garnering significant desirability and acceptance within the community. An overwhelming 95% of participants expressed that the Cocoon Mini made managing menstrual health easier for them.

“The Mini has made MH easier because bathing is possible now with access to water, a disposal bin, and light to use at night hours.” – Individual who menstruates, age 31

The Cocoon Mini pilot had many key achievements. Notably, there were no reported safety incidents throughout the pilot period, highlighting the effectiveness of the Minis in providing a safe, secure environment. Additionally, the Minis positively influenced mobility within the settlement, granting individuals the freedom to move around knowing they had dedicated spaces for managing their menstruation. This eliminated the need for them to return home and offered convenience and flexibility. Overall, the Cocoon Mini pilot successfully prioritized safety, improved hygiene practices, and enhanced mobility for individuals who menstruate in the community.

“I can now bathe three times a day when menstruating because of easy access to water and the privacy of the bathroom. The one we had before had holes in it, so I was not able to bathe during the day due to fear that people may see me.” – Individual who menstruates, age 15

Thinking About Scale

The scalability of the Cocoon Mini extends well beyond the Bidi Bidi Settlement, presenting numerous opportunities for co-designing solutions that cater to specific needs in different contexts. However, we emphasize the importance of adopting a holistic approach that combines both “hardware” (infrastructure) and “software” (social behavioral interventions) to ensure sustainable and lasting change. By integrating these two components, organizations can create comprehensive solutions that address the multifaceted nature of menstrual health management.

- Tips for holistic MH approach at scale: Consider conducting sensitivity training sessions with men, boys, and sanitation workers, as well as organizing educational forums on sexual and reproductive health. These initiatives can help prevent misinformation, raise awareness about menstrual health, STIs, and overall reproductive health, and foster a more inclusive and supportive environment.

Final Thoughts

The Cocoon Mini project served as a successful proof of concept, showcasing the effectiveness of HCD methodology in co-designing MH interventions. By engaging individuals who menstruate and key community stakeholders, we developed a solution that addressed their priorities, including safety, privacy, holistic MH management, and sustainability. Our research, published in BMC Women’s Health, highlights the potential of the Cocoon Mini as a cost-effective and impactful solution for humanitarian contexts.

Comments