“Listening to my baby heart sound was very helpful to me. I felt that my right was respected as I took in my baby monitoring. Thanks for this program. I am happy.”

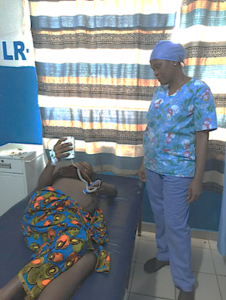

These are the words of a young Liberian mother who, as part of an innovation to improve neonatal and maternal health, was listening to the heart beat of her own fetus at the end of every contraction during her labor, using a simple handheld sonicaid ultrasound device.

Why is this approach needed?

In a low-resource country such as Liberia, where there are few midwives — according to the WHO and World Bank, only 1 midwife or nurse per 10,000 population, the second lowest number in the world after Somalia — midwives are often too overworked and overstretched to monitor the fetal heart rate regularly in every woman in labor, even though doing this essential task is necessary to detect fetal distress that could lead to negative outcomes. As a result, changes in the fetal heart rate that could indicate problems are often missed, leading to high rates of birth asphyxia in newborn infants in such settings.

Training more midwives is a long-term but absolutely crucial strategy. As shown in the recently published State of the World’s Nursing Report 2020, investment in nurses and midwives is vital to delivering Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Meanwhile, an immediate option is to train mothers in labor to listen to their fetal heart rate at the end of every contraction and notify the attending midwife if they detect any changes. If confirmed, suggesting fetal distress, the midwife would then notify a senior clinician who would undertake an immediate clinical intervention to protect the fetus from harm.

A feasibility study

The first step of such a bold and unusual potential approach is to find out if mothers are willing to monitor their own fetus during labor, and if so, if they are able to detect any changes. Our new paper in BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth emphatically shows that it is not only feasible for Liberian mothers, many of whom cannot read or write, to monitor their own fetus during labor and accurately detect changes, but that the majority found the experience positive and beneficial for their own wellbeing and that of their babies.

Key findings

The comments from participating mothers are poignant and moving and, if you have time, the authors encourage you to read the full set of comments in the additional files linked to our paper. The vast majority of participating mothers (387 out of the 400 mothers who provided comments) found the experience positive. Many commented on how much they enjoyed listening to their baby’s heart beat or hearing their baby “breathing” inside them, and that it gave them hope that their baby was alive. Several commented that hearing their baby’s heart beat gave them strength and courage to carry on while they were experiencing labor pain.

Many women commented on the negative effects of the severe pain of labor and as a result, MCAI and the Ministry of Health have recently started an initiative to administer IV paracetamol, an analgesic which is appropriate to the Liberian setting, to mothers who are requesting pain relief during labor.

Another encouraging finding was that of the 26 of 461 participating mothers for whom changes in the fetal heart rate were identified, the mothers detected these changes in 24 of these cases. Identification of these changes led to swift clinical intervention and ultimately resulted in all 26 babies, some of whom had needed further management in the neonatal unit, surviving and being discharged home healthy.

Expanding the task-sharing program to include mothers in the monitoring of their own unborn babies seems to be a welcome extension, while also providing benefits to the mothers themselves.

This finding also showed that maternal monitoring in itself is not enough as there also needed to be appropriate clinical interventions to manage any detected changes in the fetal heart rate. So in addition to maternal fetal monitoring, there also need to be in place robust clinical protocols, a skilled workforce, and appropriately equipped and supplied facilities to be able to appropriately manage any changes in fetal heart rate and deliver the Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care required to save lives and improve the quality of care.

Maternal fetal monitoring has continued in the two public hospitals that were involved in the feasibility study and, as a result of these positive findings and experiences, the Liberian Ministry of Health has agreed to expand maternal fetal monitoring to three more hospitals.

Expansion of task sharing

Innovative solutions to help overcome human-resource scarcities in low-income settings are not new. For example, because of the severe lack of doctors, the established Liberian task-sharing program involves training midwives in advanced obstetric care and training nurses in advanced neonatal care in order to reduce maternal and neonatal deaths and improve the quality of care. Expanding the task-sharing program to include mothers in the monitoring of their own unborn babies seems to be a welcome extension, while also providing benefits to the mothers themselves. As a young mother recently commented during the continuation of the maternal fetal monitoring program:

“I tell the midwife thanks for the care that was given to me. It empower me to listen to my own baby heart beat and I hope that other women will do the same.”

Comments