Lyme disease is transmitted through the bite of specific ticks and has a variety of clinical presentations, most notably a bull’s eye rash (erythema migrans) and an associated flu-like illness. Its distribution through Europe is heterogenous with a large variation in incidence between countries and within them.

Over an eighteen-year period (1998-2015) we observed a six-fold increase in cases seen in hospitals.

In the United Kingdom, information relating to infected patients’ characteristics, where they live and how they are managed within the National Health Service (NHS), is poorly understood. Currently most information is derived from Public Health England’s and Health Protection Scotland’s laboratory surveillance schemes. We are very fortunate that in England and Wales, data from all NHS hospitals are readily available, which enables the analysis of a variety of different medical conditions at a national level.

Through the analysis of these data we were able to describe which Lyme disease patients access hospitals for management and treatment, and for the first time, start to describe how patients enter and progress through NHS care.

Over an eighteen-year period (1998-2015) we observed a six-fold increase in cases seen in hospitals. Numbers of cases that require hospital admission are still relatively low compared to national surveillance figures. Most Lyme disease cases are confirmed and treated with antibiotics by a GP without the need for laboratory diagnosis or referral to a hospital. UK national surveillance figures are based solely on laboratory-confirmed cases. These figures will include a mixture of cases from primary care and hospitals. Therefore, current surveillance figures will always have a higher incidence than hospital cases alone.

Lyme disease patients attending hospitals were predominantly female and self-identified as white.

Cases that require hospital admission likely represent more clinically complex cases. They are also substantially lower than similar hospital figures reported in continental Europe. We found that cases peaked each year in August; this is consistent with people being active outdoors whilst ticks are questing for a blood meal.

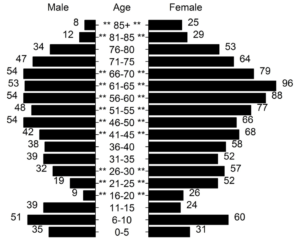

Lyme disease patients attending hospitals were predominantly female and self-identified as white. The ages most affected were young children (6-10 years old) and adults approaching retirement age (61-65 years old).

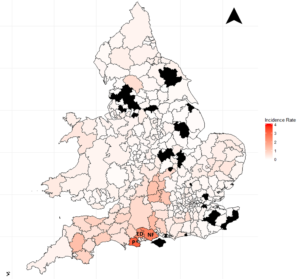

Almost all parts of England and Wales reported Lyme disease cases attending hospitals with clear hotspots of disease in central southern England. This highlights that while Lyme disease poses a risk across both countries, for most people this risk is likely to be very low as the majority of cases were found in these hotspots. Unsurprisingly, more cases were found in rural rather than urban locations. These data are based on where a patient lives rather than where they were bitten and so provides a more accurate estimate of where clinical burden will be placed on NHS hospitals.

This study is one of only a handful that describe the sociodemographics of the population affected by Lyme disease. We found a trend that increasing numbers of new patients were found in parts of the countries that are considered to have low levels of economic deprivation. The data collected gives no indication why this is the case and it is likely to be due to multiple factors. Further research is needed to identify vulnerable parts of the population which would aid in future tick bite prevention and Lyme disease awareness campaigns.

The most novel part of the research describes how patients with Lyme disease are managed within hospitals and the NHS. The majority of patients were only admitted once and stayed 4.47 days, on average. 35.5% of all patients were admitted as a day case. The variety in admission length and departments treating the patient could represent either diversity and complexity of Lyme disease symptoms or differing management strategies within hospitals. This needs to be explored as it appears that the management of Lyme disease patients in hospitals is discordant.

More than thirty percent of patients with Lyme disease enter hospital through the accident and emergency department. It is unlikely that all of these patients have acute symptoms. Why are patients accessing care through this route? It could be due to a lack of knowledge or the inability to get an appointment with a primary care clinician. This requires further exploration.

This study, like previous ones based on administrative data, may be limited by some patients not being coded correctly as having Lyme disease in hospital records. It would be difficult to truly validate the cases we identified without reading each patients written hospital notes, this would be ethically challenging. Despite these limitations, the strong trends described in this paper may indicate that these are small.

Linking this data to both primary care and laboratory data would facilitate a better account of the Lyme disease patient care pathway. Adding to our understanding of these factors could lead to better patient care, education and resource allocation.

Lyme disease patients are seen at most hospitals across England and Wales

This research has highlighted that Lyme disease patients are seen at most hospitals across England and Wales. However, Lyme disease presentation in hospital is an uncommon event except in southern-central England. Patient care within the NHS is not streamlined and may reflect variation in patient management or the range of Lyme disease symptoms. This work can provide a reference point to future Lyme disease research in the United Kingdom and any Lyme disease hospital-based research internationally.

Being aware of the signs & symptoms of Lyme Disease is important so that you can receive early diagnosis and treatment from your family doctor. Symptoms typically develop up to 3 weeks after being bitten by a tick and include a spreading circular red rash or flu-like symptoms. When you visit your GP or call NHS 111, remember to tell them where you have been and if you remember being bitten. More information is available on https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/lyme-disease/, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/lyme-disease-guidance-data-and-analysis, and https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng95.

Comments