Juliana[1] was lost in thought. Like her mother, she had learned to support women through pregnancy and childbirth over several years of apprenticeship, delivering at least 400 healthy babies. The women she helped paid her whatever they could afford. But her greatest reward was the satisfaction of successful delivery of a healthy mother and newborn. As a reflection of her track record of success as a service provider and her standing in the community, Juliana had recently been appointed the head of the community women’s association.

Complications after delivery could be harmful to Juliana’s reputation, threatening her livelihood and her standing in the community. This threat was behind Juliana’s worry. In the delivery room lay a mother who was bleeding despite Juliana’s best efforts. A few hundred meters away, in the local clinic, there was a doctor, with supplies and equipment, who might be able to help Juliana’s client. Sending the mother to the clinic immediately was the right choice, one that Juliana had decided to make, but it could come at a personal and social cost.

Postnatal care – important but rare

Maternal deaths commonly occur within 48 hours of childbirth, predominantly from severe bleeding, hypertensive diseases, and infections – complications which may arise without warning. Therefore, the World Health Organization recommends that every mother receive postnatal care within 48 hours of delivery, with regular assessments to facilitate early diagnosis, treatment, and referral in the event of complications.

More than six out of ten childbirths in Nigeria are not supported by a skilled health care provider. In most cases, these women turn to a traditional birth attendant (TBA), an informally-trained and community-based provider of pregnancy-related care that works independently of the health system. In Nigeria, less than two in ten mothers who give birth outside the facility, often supported by TBAs, receive postnatal care.

The role of TBAs

Our previous qualitative study indicated that a TBA’s advice influences decision-making by his/her clients, including the choice to visit a health facility. Many TBAs in our study referred their clients for antenatal ultrasound tests and medication. However, they voiced concerns about the reputational risk and potential for client loss if a TBA referred a client to a skilled health worker postnatally, particularly if there were complications following delivery. Our interviews suggested that monetary rewards could potentially offset these reputational costs to the TBA and increase referrals for postnatal care.

In the absence of rigorous studies of the effectiveness of this intervention, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to estimate the impact of individual cash rewards for maternal referrals on postnatal care use among both mothers and their newborns within 48 hours of delivery. The trial enrolled 207 TBAs in Ebonyi State, Nigeria, from communities that had at least one primary health care facility with a health care provider offering postnatal care. We randomized each TBA to the intervention or control group. TBAs in the intervention group received USD 2.00 for every maternal client that attended postnatal care within 48 hours of delivery. Irrespective of their group, all TBAs were informed of the benefits of postnatal care within 48 hours of delivery for maternal and neonatal survival, encouraged to refer their clients within this time window, and offered a reward of USD 0.70 for informing the study team of clients they had supported during delivery.

Our findings

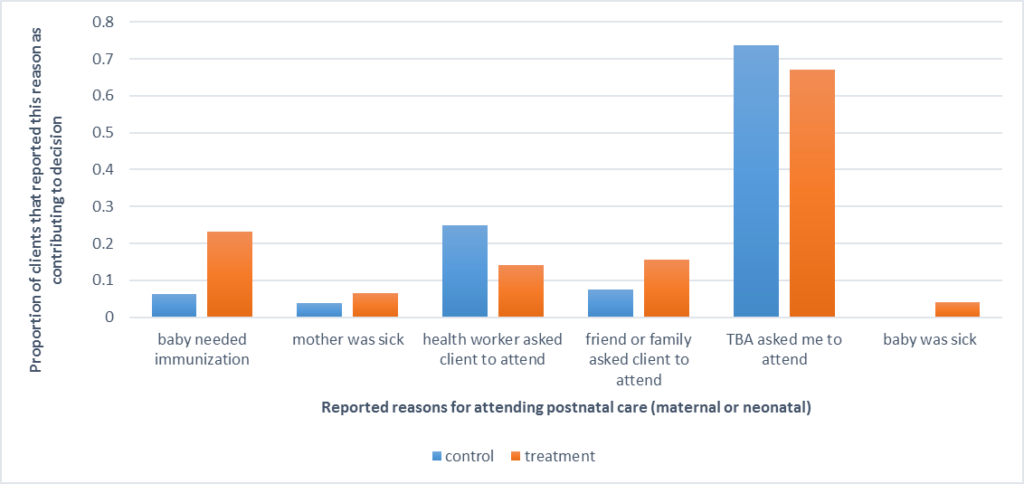

We found that the intervention was successful at increasing postnatal care use. The probability that a maternal client in the intervention group attended postnatal care within 48 hours of delivery was 15.4 percentage points higher than for maternal clients in the control group. Our intervention only rewarded TBAs in the intervention group for referring mothers to postnatal care, however, the intervention also increased postnatal care checks for newborns. In about seven out of ten cases, mothers reported that the TBA’s advice was an important motivation for attending postnatal care for themselves or their newborns (see figure).

Thus, cash incentives to TBAs did increase postnatal care use. Nonetheless, fewer than 20 percent of mothers or newborns in the intervention group received postnatal care within 48 hours of delivery, leaving most clients of TBAs still vulnerable to complications within this critical window. Furthermore, obtaining postnatal care in a health facility from a skilled provider did not guarantee that mothers or their newborns were assessed appropriately, as health providers addressed only 42 percent of recommended actions from the postnatal care guidelines developed by the World Health Organization.

Every mother and her newborn should be supported before, during, and after delivery by a skilled and equipped provider. Where mothers continue to patronize informal providers like Juliana, our study shows that monetary rewards for referrals can link these mothers to skilled care during the postnatal period. Postnatal care can be particularly consequential and lifesaving for these mothers and newborns that do not receive skilled support during pregnancy and delivery. However, for postnatal care to save lives, skilled health care providers must deliver high-quality care. Therefore, where implemented, cash incentives for referrals should be complemented with interventions that address other demand- and supply-side barriers to high-quality, skilled health care.

[1] A fictional case based on qualitative research conducted by the study team.

Comments