A recent study published in BMC Evolutionary Biology demonstrated that a transplanted soft coral from the Caribbean Sea (Antillogorgia bipinnata) changed its shape consistently as the corals living in the new environment. This type of manipulation known as “common garden experiments” allowed the authors to determine the adaptive value of that change that means life or death for a species across a depth gradient.

This individual capacity is called phenotypic plasticity when the same genotype can exhibit several phenotypes due to environmental influences, and it is the equivalent of a person getting a tan after some holidays on a sunny beach.

Of course, there are many different types of skin and some people can hardly get any tan whereas others can be unrecognizable. The coral studied by Iván Calixto-Botía and Juan Sánchez from the University of the Andes in Bogotá, Colombia, is the kind that changes dramatically its tree-like shape to an extent that the extremes have even been considered as different species.

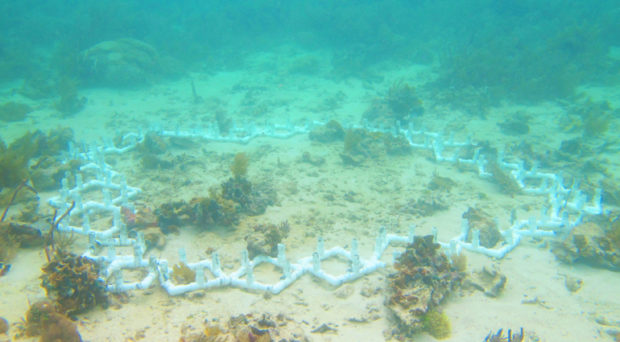

That observation was also published in BMC Evolutionary Biology by Sánchez and collaborators ten years ago. Antillogorgia bipinnata changed the size of its branches up to ten times from shallow-water down to 40 m at the Belize barrier reef but no genetic differentiation was found.

The authors since then were wondering what was the limit of such plasticity, the adaptive canvas and if that such shape transformation can lead to an isolated population at the extremes.

Marine scientists studying biodiversity in the tropics are always amazed by the great number of species living in the same environments. It is difficult to image a process leading to species diversification without geographic barriers.

Scientists like Calixto and Sánchez are betting on plasticity as the first step to speciation without geographic barriers only with some type of selective effects at the extremes. They are now tracking the footsteps of selection in the genome of the species and the effects of depth on the coral reproductive synchronization.

Both authors work at La Universidad de los Andes, Colombia

Comments