Field work is hard. It’s hard because you have to get up early, work long hours in the burning sun or pouring rain, but the hardest is that you cannot predict what is going to happen. In 2013, when we went to the Biological Station of Queen’s University near Kingston, Canada to work on wild tree swallows, we didn’t know that the experiment that we had carefully designed and had discussed over and over would ultimately fail miserably because of forces much greater than us.

Mother Nature decided not to approve our study, but instead, to teach us something else. And although we still regret that our plans didn’t work out, we think we might have been lucky to learn something about the life of these birds that we wouldn’t have otherwise.

The species we studied

Tree swallows are small (~20g) birds that live in socially monogamous pairs and (like many other passerine birds) work very hard to raise their kids that grow very fast: usually 4-6 chicks hatch from tiny eggs smaller than a penny and grow to adult size within three weeks.

As a consequence, the chicks are always hungry, and the parents need to fly around a lot to catch enough flies to feed their hungry chicks. So what makes them able to do that?

One hypothesis is that the glucocorticoid hormone, corticosterone, fuels the increased energetic demands during reproduction. A previous study in the same population found that when the number of chicks was experimentally increased, the mothers also increased their corticosterone levels, probably as a response to the increased demand.

However, corticosterone is also known as a ‘stress hormone’; therefore, high levels of this hormone will cause parents to abandon reproduction completely and divert energy to themselves. Thus, animals need a careful, internal balance that also responds to outside conditions.

What did we do?

To test whether corticosterone is causally related to the intensity of parental effort, we increased corticosterone levels of female tree swallows whose chicks were four days old. To do so, we implanted a tiny hormone-containing biodegradable pellet under their skin. Our goal was to see if they would change their reproductive effort. So this was the plan, but that was literally washed out by the rain.

To put it simply, the summer of 2013 in Canada was terrible. The temperatures were way below the seasonal averages, it was raining a lot, and when we saw some snowflakes during the middle of the breeding season, we knew it was going to be hard for the swallows.

Tree swallows feed exclusively on flying insects, so the cold, windy, rainy weather is the worst that you can imagine for these birds. There are no flying insects in this weather and even if the parents are doing their best to find some, the babies are left in the nest and they are cooling down very fast.

So what did we discover?

Not surprisingly, the repeated, cold temperatures and heavy rains caused most of the birds in our population to abandon reproduction.

Not surprisingly, the repeated, cold temperatures and heavy rains caused most of the birds in our population to abandon reproduction. Almost all nestlings in our study population died during these days, resulting in population-wide mortality rates reaching over 90%.

However, these cold bouts gave us an opportunity to test how environmental conditions interact with the hormone treatment to influence the survival of the young. We found that when the weather was especially cold and rainy, corticosterone treated and control treated nests had similar brood survival rates.

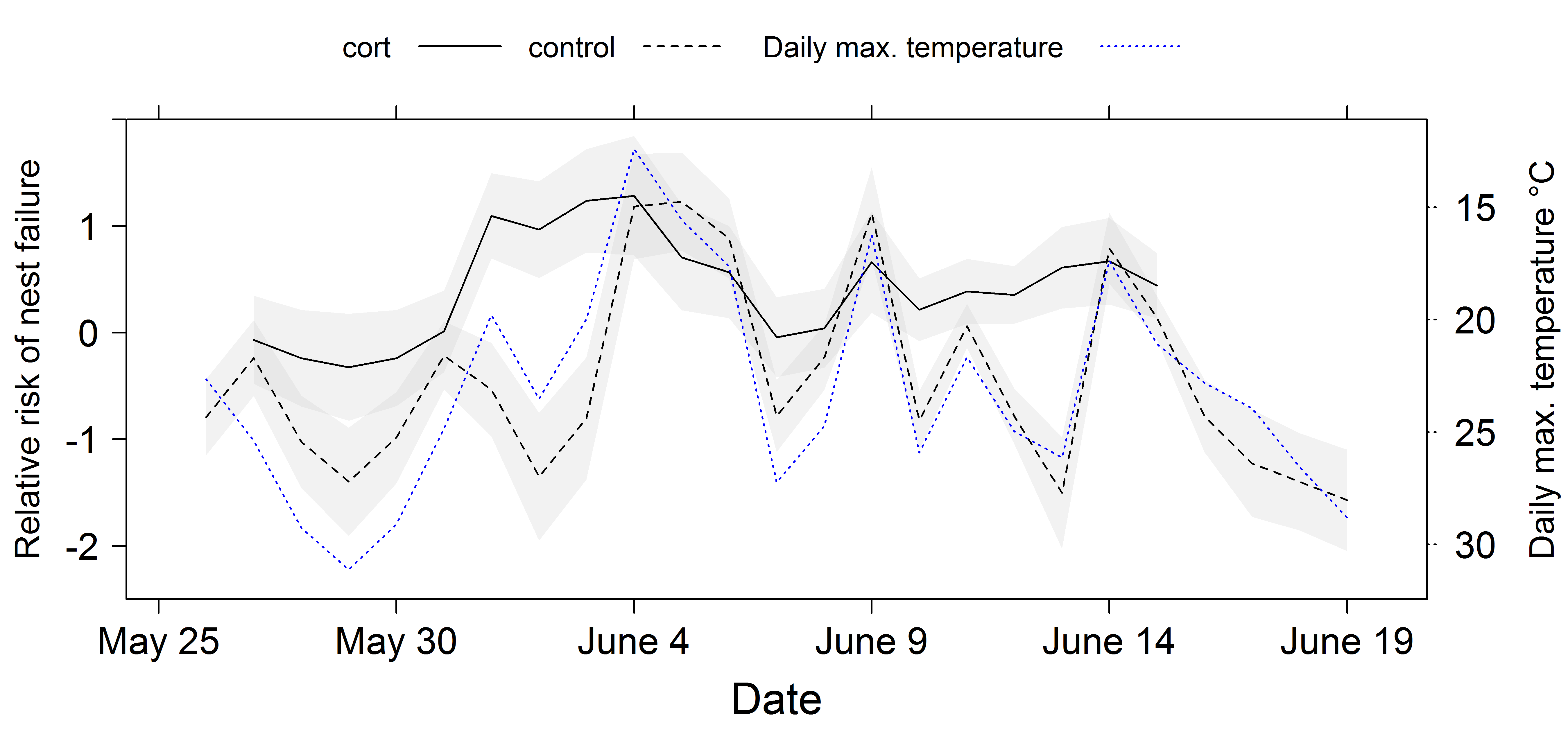

However, when the weather was better, corticosterone treatment hastened brood mortality. In fact, control treated nests’ survival followed the weather patterns exactly, whereas corticosterone treated nests showed a mismatch with environmental conditions.

In the graph above, the black lines show the brood mortality and the blue dotted line shows the temperature (note that the scale is reversed on the right axis, so the highest peaks show the lowest temperatures). The brood mortality in the control group follows the temperature closely, whereas the corticosterone implanted group (solid black line) is mainly disconnected from the weather. In cold weather, the lines of the two groups overlap, whereas in warm weather they are more distinct.

Moreover, we found that how much parents invested into their offspring before the implantation also mattered, in an interesting and unexpected way. High female feeding rates before implantation meant that the brood would survive longer.

Surprisingly, however, even though we only manipulated females, males also responded to their partners’ altered states. High male feeding rates prior to implantation increased survival only in the control group, the reverse was found in the males whose partners received the hormone treatment.

It seems that males that were investing the most effort early on are more sensitive to changes in weather, and less able to persist with their high level of investment after their partner was hormone-implanted.

Adapting to challenging conditions

As the occurrence of unpredictable weather is likely to increase with climate change, disturbed populations may not be able to respond adaptively to even more challenging conditions.

These results showed us that the effects of hormone levels on reproductive success are context dependent. Although we were not able to test whether an increase in corticosterone makes the parents work harder, it seems that they became more susceptible to lose their chicks when the environment turned against them. Increasing the corticosterone levels to boost your parental effort might be a risky game.

Tree swallows are declining rapidly in the area where we studied them. As the occurrence of unpredictable weather is likely to increase with climate change, disturbed populations, with individuals that are already undergoing many stressors and have higher levels of glucocorticoids, may not be able to respond adaptively to even more challenging conditions.

Comments