Lymphatic filariasis

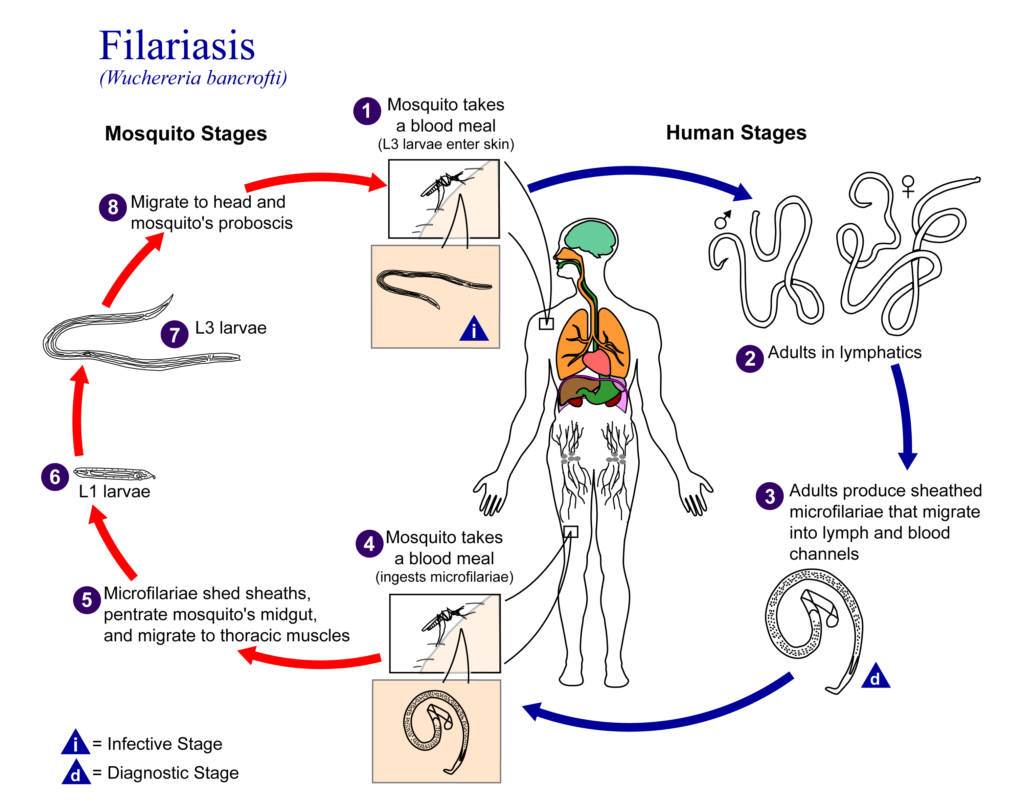

Lymphatic filariasis, a disease common in tropical and subtropical areas, is spread by mosquitoes and caused by infection with parasitic filarial worms. Once infected, larval worms grow into adult worms and mate to produce microfilariae (mf). The mf are then collected by mosquitoes during a blood meal, and the infection can be spread to another person.

Infection can be diagnosed using tests for circulating mf (microfilaremia) or parasite antigens (antigenemia), or by ultrasound imaging to detect live adult worms.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends annual mass treatment of entire populations for at least five years. The main treatment is a two-drug combination of albendazole and a microfilaricidal (antifilarial) drug, either diethylcarbamazine (DEC) or ivermectin.

Albendazole alone, given biannually, is recommended for areas co-endemic for loiasis, where DEC or ivermectin should not be used due to the risk of serious adverse events.

Albendazole for lymphatic filariasis

Both ivermectin and DEC rapidly clear mf infections and can suppress their reappearance. However, mf production will resume due to the limited effects on adult worms. Albendazole was considered for lymphatic filariasis after a study reported that high doses given over several weeks caused serious adverse reactions suggestive of adult worm death.

A WHO informal consultation report then proposed that albendazole has a killing or sterilizing activity on adult worms. In 2000, GlaxoSmithKline began donating albendazole for lymphatic filariasis treatment programs.

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) investigated the effectiveness and safety of albendazole alone or in combination with ivermectin or DEC. Several systematic reviews of RCT and observational data followed, but it was unclear whether albendazole was of any benefit for lymphatic filariasis.

In light of this, a Cochrane Review published in 2005 has been updated to assess the effects of albendazole in people and communities with lymphatic filariasis.

The Cochrane Review update

Cochrane Reviews are systematic reviews that aim to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified criteria to answer a research question. Cochrane Reviews are also updated when new evidence becomes available.

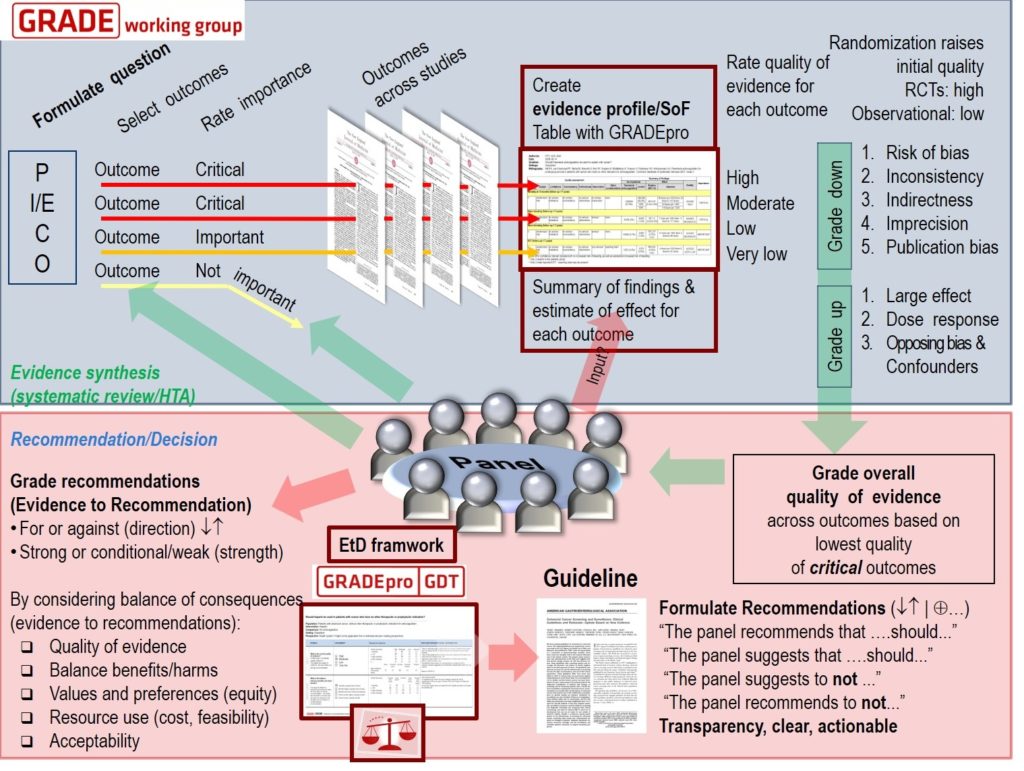

Cochrane methods minimize bias in the review process. This includes using tools to assess the risks of bias in individual trials and GRADE the certainty (or quality) of evidence for each outcome.

The updated Cochrane Review, ‘albendazole alone or in combination with microfilaricidal drugs for lymphatic filariasis’, was published in January 2019 by the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group and COUNTDOWN consortium.

The Review sought RCTs that assessed:

1) albendazole vs placebo;

2) albendazole plus DEC vs DEC; and

3) albendazole plus ivermectin vs ivermectin

Outcomes of interest included measures of transmission potential (mf prevalence and density), markers of adult worm infection (antigenemia prevalence and density, and adult worms detected by ultrasound) and adverse events.

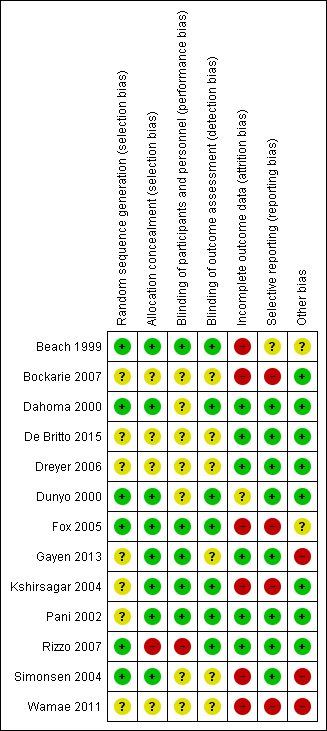

Using electronic searches, the authors attempted to identify all relevant trials up to January 2018 regardless of language or publication status. Two authors independently assessed studies for inclusion, assessed the risks of bias, and extracted trial data.

What the research says

The Review included 13 trials with 8713 participants. To measure treatment effects, meta-analyses were used for parasite prevalence and adverse event outcomes. Tables were prepared to analyse parasite density outcomes, as poor reporting meant the data could not be pooled.

The authors found that albendazole alone or added to a microfilaricidal drug makes little or no difference to mf prevalence over two weeks to 12 months after treatment (high-certainty evidence).

They do not know if there is an effect on mf density between one to six months (very low-certainty evidence) or at 12 months (very low-certainty evidence).

Treatment with albendazole alone or added to a microfilaricidal drug makes little or no difference to antigenemia prevalence between six to 12 months (high-certainty evidence).

The authors do not know if there is an effect on antigen density over six to 12 months (very low-certainty evidence). Albendazole added to a microfilaricidal drug may make little or no difference to adult worm prevalence detected by ultrasound at 12 months (low-certainty evidence).

When given alone or as a combination, albendazole makes little or no difference to the number of people reporting an adverse event (high-certainty evidence).

Implications for practice

The Review found good evidence that albendazole alone or in combination with microfilaricidal drugs has little or no effect on completely clearing the mf or adult worms up to 12 months after treatment.

There was no convincing data across studies of an effect on mf density or adult worm viability.

Given that the drug is part of mainstream policy, and the WHO now also recommend a triple‐drug regimen, it seems unlikely researchers will continue to evaluate albendazole in combination with DEC or ivermectin.

However, albendazole alone is recommended in areas endemic for loiasis. Therefore, this remains a priority for research to know whether the drug is effective in these communities.

A macrofilaricidal drug with a short treatment regimen could make a significant impact on filariasis elimination programs. One such drug is currently undergoing preclinical development, and has been covered in a recent BugBitten blog.

Article: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003753.pub4/full

Comments