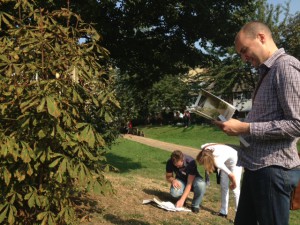

A few weeks back, staff here at BioMed Central took some time out to turn the tables on publishing science by becoming citizen scientists. Swapping the office environment for the great outdoors (well, a park in London), a small band of dedicated data-gatherers joined organisers of a new initiative lead by Imperial College London to survey the health of the UK’s trees. Here, we talk to Open Air Laboratories (OPAL) about how a new generation of enthusiastic amateurs are helping to crowdsource answers to some of sciences’ most intractable puzzles, and how even an urban jungle can yield useful data on the spread of deadly plant disease.

What is OPAL?

Open Air Laboratories (OPAL) led by Imperial College London, is a nationwide partnership initiative funded by the Big Lottery Fund. Our aim is to inspire communities to discover their local environment through our surveys whilst contributing to valuable environmental research.

What is the aim of the Tree Health Survey?

As with our other six surveys our main aim is to get people outdoors exploring their local environment and, in this case, learning about our native trees and some of the pests and diseases that affect them. By gathering vital information on pests and diseases affecting our native Oak, Ash and Horse Chestnut, the public will be able to help scientists understand more about their impact and their changing distribution, as well as how different pests and diseases interact with each other.

Many of the pests and diseases we are looking at are the equivalent of our common colds and flus but some are much more serious. By having more people out on the ground looking out for pests and diseases the public will be acting as an early warning system helping the authorities spot potentially devastating threats becoming established in this country. Who knows, you may be the first person to spot the first Emerald Ash Borer or Pine Processionary Moth caterpillar thus saving valuable time and effort, as well as our native trees.

How long has the survey been running and what have you found so far?

We launched the survey in May of this year and so far over 50,000 surveys have been sent out. 20,000 of these have been sent to schools, over 10,000 have been distributed by OPAL partners and associates such as the Food and Environment Research Agency (FERA) and Forest Research and a further 10,000 survey packs have been requested by the public.

Although the results have not yet been verified, early indications are that most trees surveyed are pest and disease-free. Of the three species surveyed so far, Horse Chestnuts most often displayed symptoms of pests and diseases; about 65% reportedly had leaf blotch, Leaf-miner, bleeding canker or scale.

How can people get involved in conducting their own survey, and what does each survey involve?

All you need to do is log onto our website to sign up for a survey pack or alternatively download it from our resources section. The survey, designed in collaboration with Forest Research and FERA includes activities such as identifying tree species, measuring height and examining trees for signs of poor health such as leaf yellowing.

We are also asking participants to look out for a range of pests and diseases, particularly those that affect our most loved trees – Oak, Ash and Horse Chestnut. Many of these pests and diseases are common and only have an aesthetic impact on our trees. However, we are also asking people to look out for six ‘Most Unwanted’ pests and diseases which, if found, could have a very serious effect on our woods if they spread across the UK.

The pack contains all you need to take part in the survey which should take around 30 minutes to complete.

The survey is best carried out when leaves are still on the trees and signs of pests and diseases are easier to spot. So we need you to take part in the next few weeks and ensure you send us your results.

Do you need to know anything about trees and/or go out into the countryside to take part?

No, the pack contains easy-to-follow instructions and all the support you’ll need. We’ve included a fold-out ID poster to help you identify tree species, including the three species we want people to focus on, Oak, Ash and Horse Chestnut. The survey is a great introduction to trees and a perfect way to learn how to identify some of our native species. Any tree can be surveyed, whether in the countryside or in the heart of your local city. We want as many trees as possible to be surveyed as all of the information submitted will help scientists build up a picture of tree health across the UK

No, the pack contains easy-to-follow instructions and all the support you’ll need. We’ve included a fold-out ID poster to help you identify tree species, including the three species we want people to focus on, Oak, Ash and Horse Chestnut. The survey is a great introduction to trees and a perfect way to learn how to identify some of our native species. Any tree can be surveyed, whether in the countryside or in the heart of your local city. We want as many trees as possible to be surveyed as all of the information submitted will help scientists build up a picture of tree health across the UK

How important do you think citizen science projects such as this are for the future of scientific research?

Citizen science enables a greater amount of data to be collected, as well as raising awareness about specific issues and creating a new generation of scientists. We’re seeing more and more citizen science projects take off, from crowdsourcing genomic datasets in ash trees, through to analysing real life cancer data. Ecological surveys in particular are given an extra boost in terms of data as individuals can contribute findings from their own private land, data which would otherwise be restricted.

Smartphones are just one of the tools scientists are using to develop ‘games’ as a way of increasing the number and range of participants, as well as the amount of data collected. Social networking sites have also become a great way of harnessing more people, as well as computers, to take part in research. For instance, ‘Fraxinus’ is a Facebook game which could increase the speed with which scientists are able to isolate the genes that encode for resistance to the ash dieback pathogen. Citizen science certainly has the potential to make a serious impact on scientific findings.

What have you done to minimise error in the data collected?

We have carefully developed the survey and supporting material to minimise the opportunities for error and improve participants’ confidence. Photos can be uploaded to allow verification of pests and diseases by our experts. We also collect background information to help us assess the level of confidence we might have in the data. We can then give stronger weight to results collected by those likely to be more accurate. We also run an extensive training programme for people who will go on to lead surveys and we have Community Scientists on the ground who can work directly with participants, as well as having lots of supporting material in the packs and online.

When will we learn the results of your latest survey?

The results will be analysed by experts at Forest Research and we aim to publish the results on the OPAL website from summer of next year.

Will the data and results be made openly available for all participants to access?

Some of the verified biological data from the early OPAL Surveys, such as the Soil and Earthworm survey, launched in 2009, is already available on the National Biodiversity Network (NGN) Gateway. This was significant as prior to the survey, the NBN Gateway only had a single Earthworm record! We hope that by summer 2014, the OPAL website will have a facility to allow anyone to access and query data from most, if not all of the OPAL surveys, including the data from the Tree Health Survey.

Did the BioMed Central staff manage to find anything particularly noteworthy in their survey?

Three pests and diseases were found in the area surveyed; horse chestnut leaf miner, bleeding canker and ash key gall. The most prominent of these was the Horse Chestnut leaf miner, a micro-moth which arrived in the UK from Europe in 2002. The moth caterpillars feed by tunnelling inside the leaves. Severely damaged leaves shrivel and turn brown by late summer, and then leaves fall early. It feels as though autumn has come early in London with these trees being affected across the city! Horse Chestnut Leaf-miner does not permanently damage the tree, but it is an introduced pest and its rate of spread is of interest to scientists.

Three pests and diseases were found in the area surveyed; horse chestnut leaf miner, bleeding canker and ash key gall. The most prominent of these was the Horse Chestnut leaf miner, a micro-moth which arrived in the UK from Europe in 2002. The moth caterpillars feed by tunnelling inside the leaves. Severely damaged leaves shrivel and turn brown by late summer, and then leaves fall early. It feels as though autumn has come early in London with these trees being affected across the city! Horse Chestnut Leaf-miner does not permanently damage the tree, but it is an introduced pest and its rate of spread is of interest to scientists.

Horse chestnut bleeding canker is caused by a bacterium. It is an introduced disease which suddenly appeared in the early 2000s and has spread rapidly. It attacks and kills the bark of infected trees and ultimately the tree can die if the infection is very severe. A few of the horse chestnuts we looked at had leaf miner damage and bleeding canker but scientists have not found a link between the two.

The slightly less obvious pest was the ash key gall. Ash key galls are caused by a mite and are very common. They actually indicate a healthy tree, as the mites prefer healthy trees. The galls make Ash keys heavier, so wind dispersal is hindered and the seeds are not carried as far.

Further reading:

Get involved!*

Sign up for a free survey pack.

*Please note that now Autumn is upon us, surveys are now closed for data collection, commencing again in Spring 2014.

Comments