The transparent reporting of clinical trials is vital for decision making in healthcare. Misreporting of clinical trials is a growing problem, with a staggering number showing significant discrepancies between the information provided when the trial is registered and the data reported in publications.

Over the course of a clinical trial it is by no means unheard of for a protocol to evolve, with changes being made to the methodology and outcomes being measured. It is in fact so common that the ‘gold standard’ of reporting – CONSORT – has a whole section dedicated to just this. The main problem lies in not reporting these changes, which can undermine the overall validity and integrity of the research.

Registering clinical trials is not just about box ticking

If the trial registry is updated when protocol amendments are made, it provides a clear chain of evidence for all changes, ensuring transparency of the research.

Clinical trials are widely considered to be one of the best ways to test the safety and effectiveness of treatments in medical research. In 2013, the AllTrials campaign was initiated, calling for all past and present clinical trials to be registered and their results reported. Since then, the campaign has attracted the support of 87,510 people and 639 organisations.

When a clinical trial is registered, it is the first point at which specific data relating to a clinical trial becomes publicly visible. Great headway has been made in the adoption of clinical trial registration, but for many this process has become a mere box-ticking exercise. In all too many cases, the trial record is forgotten about once the registration number has been obtained, even when there are significant deviations from the original protocol throughout the course of the trial.

When a clinical trial is registered, it is the first point at which specific data relating to a clinical trial becomes publicly visible.

Prospective trial registration is fundamental to the prevention of reporting bias in medical research. If the trial registry is updated when protocol amendments are made, it provides a clear chain of evidence for all changes, ensuring transparency of the research. However, if the registry is out of date, then the trialist has no leg to stand on if they are called up for selective reporting.

Go COMPare

Before a study begins, investigators should pre-specify what they intend to measure. For example, in a study looking at treating self-blame in adults with depression, the primary outcome measure could be depression before and after treatment.

Selecting these outcomes in advance of conducting a clinical trial should lead to an accurate representation of the intervention studied. This does not mean that something unexpected cannot happen, simply that the study must discuss the pre-specified outcomes (even if they do not return significant findings) and interpret any unexpected results with caution. By changing the reported outcomes or adding new ones depending on the nature and/or significance of the results, authors could potentially mislead the reader of an article into thinking that the results are more meaningful than they actually are.

For many years, the issue of outcome switching has been a hot topic in many reviews and research papers, from the widely cited 2004 article by Chan et al to an article publishing in our very own BMC Medicine, which highlighted wide-spread inconsistencies with registered and published outcome measures across a wide range of articles spanning a range of different registries and journals.

The COMPare project – 87% of the 67 trials examined contained misreported outcome measures.

COMPare (CEBM Outcome Monitoring Project) is a large-scale project based at the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, at the University of Oxford designed to address the wide-spread problem of outcome switching in clinical trials.

In phase 1 of the COMPare project, trials published in top medical journals were compared to their original clinical trial records, so that pre-specified and reported outcomes could be compared. It was found that a shocking 87% of the 67 trials examined contained misreported outcome measures.

Following the publication of COMPare’s findings, the editors of the journal Annals of Internal Medicine responded, intimating that the issues related to outcome switching lies at the door of the registries the trials are registered in, saying that the “registry information is often poor quality, with outcomes poorly pre-specified”. An ironic statement considering that there was sufficient information in the registries for the COMPare team to evaluate reporting bias, suggesting that many editors and peer reviewers do not actually look at the clinical trial record when considering a manuscript for publication, as discussed in a controversial article published in PLOS ONE. What is not clear, however, are the reasons for these deviations, as the authors did not choose to update the trial record, and thus are now all tarred with the same brush [sic].

Editors, reviewers and readers have been actively encouraged to compare the information listed in a clinical trial registry with what is reported in a manuscript.

Editors, reviewers and readers have been actively encouraged to compare the information listed in a clinical trial registry with what is reported in a manuscript, particularly with regards to outcome measures. It is therefore vital that trialists are motivated and encouraged to maintain and update their clinical trial records whenever there is a change to the study. If a trialist ensures that the information listed in the registry is transparent and up to date, it can help to overcome the hurdles that selective reporting and outcome bias could throw in their way.

Always leaving a trail

The ISRCTN registry is dedicated to the complete and transparent reporting of clinical trials. In order to ensure that all trial records are as up-to-date and accurate as possible, we are working to tackle the issue on two fronts. Firstly, we actively encourage investigators when their study is registered to contact us if there are any changes to the protocol, so the record can be updated. Secondly, we work through old records and contact investigators in order to find out whether there have been any changes to the study protocol so that the record can be updated.

When a change is made to a record, the original information stands alongside the new, providing a clear audit trail, thus ensuring the validity and integrity of the record. For example, in record ISRCTN02553381, a number of sections have been updated including the secondary outcome measures and study dates. This is summarized in a dedicated “Editorial Notes” field at the end of the record, as well as displaying original and updated information side by side in the free-text fields.

Trialists are also given the opportunity to update their trial records to highlight whether their study has been stopped prematurely, distinguishing it from completed studies that reached their planned conclusion. Despite this, of over 14,000 registered studies, less than 3% are marked as having been stopped, a low number considering the large numbers of terminated trials out there.

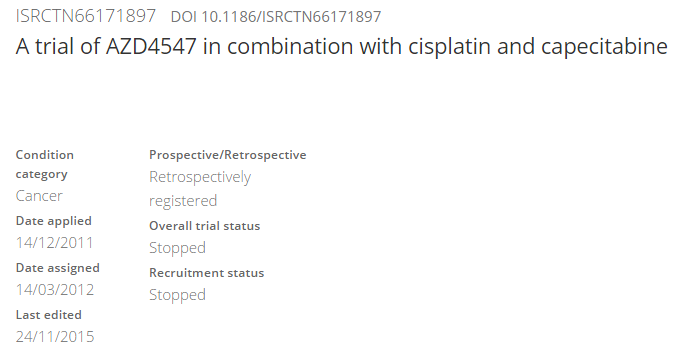

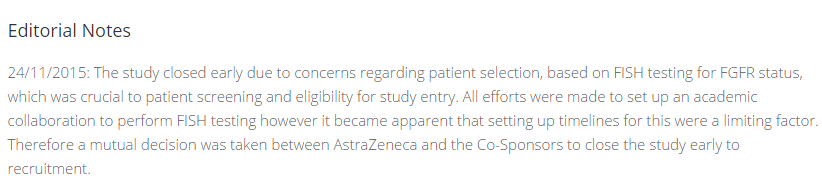

Trials can be abandoned for any number of reasons, from lack of funding to problems with recruitment. Specialized trial and recruitment status override fields are included so that the trial can be highlighted as having been stopped. For example, in ISRCTN66171897, the study was stopped due to concerns regarding selection of participants to take part. The investigator in question was able to both highlight this, and include a statement concerning the specific reasons at the end of the record.

If you have registered your trial with ISRCTN and think your record is due an update, contact us at any time!

Comments