Kidney cancer poses a significant healthcare burden in the UK, with 13,000 new patients diagnosed annually, a 52% survival rate, and nearly 5,000 patients dying each year. The US faces similar problems, with 81,000 new cases and nearly 14,000 deaths annually. The incidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has more than doubled in the last 50 years and is increasing by 2-3% every year.

Once the cancer has spread (metastasized) kidney cancer has a poor 5-year survival rate of 12%. Patients with metastatic kidney cancer can be offered a range of drugs, including targeted agents and immunotherapy, but response rates vary between patients. Currently there is no way to predict who will respond to which drugs.

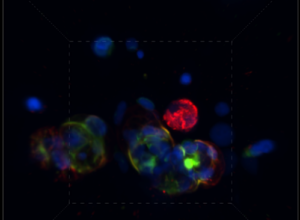

Pear Bio is developing a new functional precision medicine test that uses a fresh sample of the patient’s tumor and a blood sample and tests a range of treatments against the sample. It takes fresh tissue samples, grows them in the lab as “micro-tumors”, applies different treatments and then takes images through a microscope to measure how well the different treatments work. The eventual aim is to develop a test that can help better match patients to different treatments.

The PEAR-TREE study, led by Prof. Tran at the Royal Free Hospital, lays the foundations for this. We aimed to recruit patients who were due to have an operation for their kidney cancer. Patients had surgery as standard and donated 40 ml of blood. The blood sample and tumor sample surplus to diagnostic purposes were sent to the Pear Bio lab. In the lab, we tried to grow the tissue and then tested different drugs that are normally used in patients with metastatic kidney cancer. The lab team looked at how well the drugs worked, whether some drugs worked better than others, whether some samples had different responses to each drug, and whether we were correctly measuring the mechanism by which drugs affect the cancer cells, including the effect of immune cells.

We recruited 25 patients who were due to have surgery for their kidney cancer as part of usual care; of these, we were able to obtain usable specimens from 20 patients. All of these, all 20 grew in the lab, and we tested a range of six treatments and five combinations against the different specimens.

It is possible to take tumor and blood samples from patients with kidney cancer, grow them in the lab, treat them with different drugs, and measure the responses to the different drugs.

Surgical samples deliver quite “large” pieces of tumor to the lab – on average 430 mg, which translates into about 9 million cells. As a result, the lab team were able to optimize the workflow to make sure that the tumors grew well in the lab and could be treated with the different drugs. We were able to show that there are clear differences between patient samples in their responses to the same drugs, and differences within patient samples in response to different drugs.

Although this has been a purely lab-based study, it has shown that it is possible to take tumor and blood samples from patients with kidney cancer, grow them in the lab, treat them with different drugs, and measure the responses to the different drugs. While we cannot talk about patient benefit at the moment, the PEAR-TREE study lays an important step forward. Our next step is to explore this in a new study, PEAR-TREE2, which will recruit a much larger group of patients with metastatic kidney cancer.

Finally, we would like to acknowledge all of the support and involvement we have had from the clinical and research teams at the Royal Free Hospital, UCL, Kidney Cancer UK, and most of all patients and families, without whose willingness to donate “leftover” tissue and blood none of this work would be possible.

Comments