After the invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, more than 14 million Ukrainians had to flee their country, or were internally displaced, giving rise to “the largest human displacement crisis in the world today”. Ukrainians exposed to armed conflict and migration are likely to have low levels of mental health status and seek help. Our evidence supports this concern.

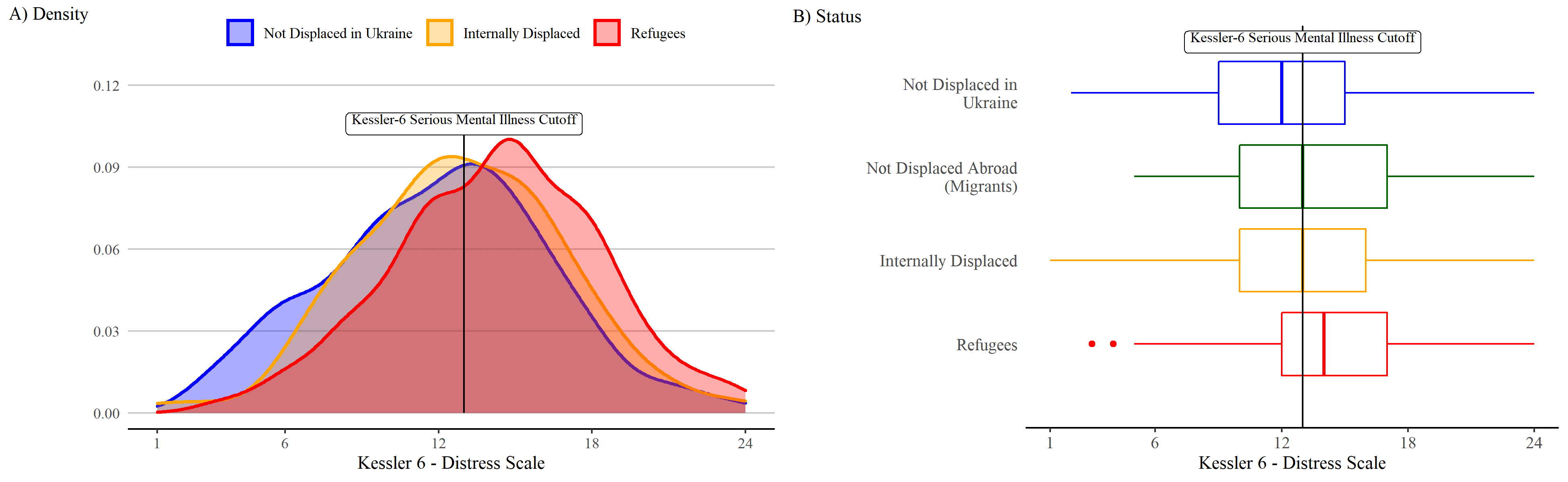

We provided an early online assessment of the mental health of 1165 Ukrainian help-seekers across the European Union and Ukraine. Ukrainian refugees, internally displaced, and migrants are at exceptionally high risk of depression and psychological distress. Figure 1 below illustrates the disparity of stress levels among Ukrainians seeking help online by migration status.

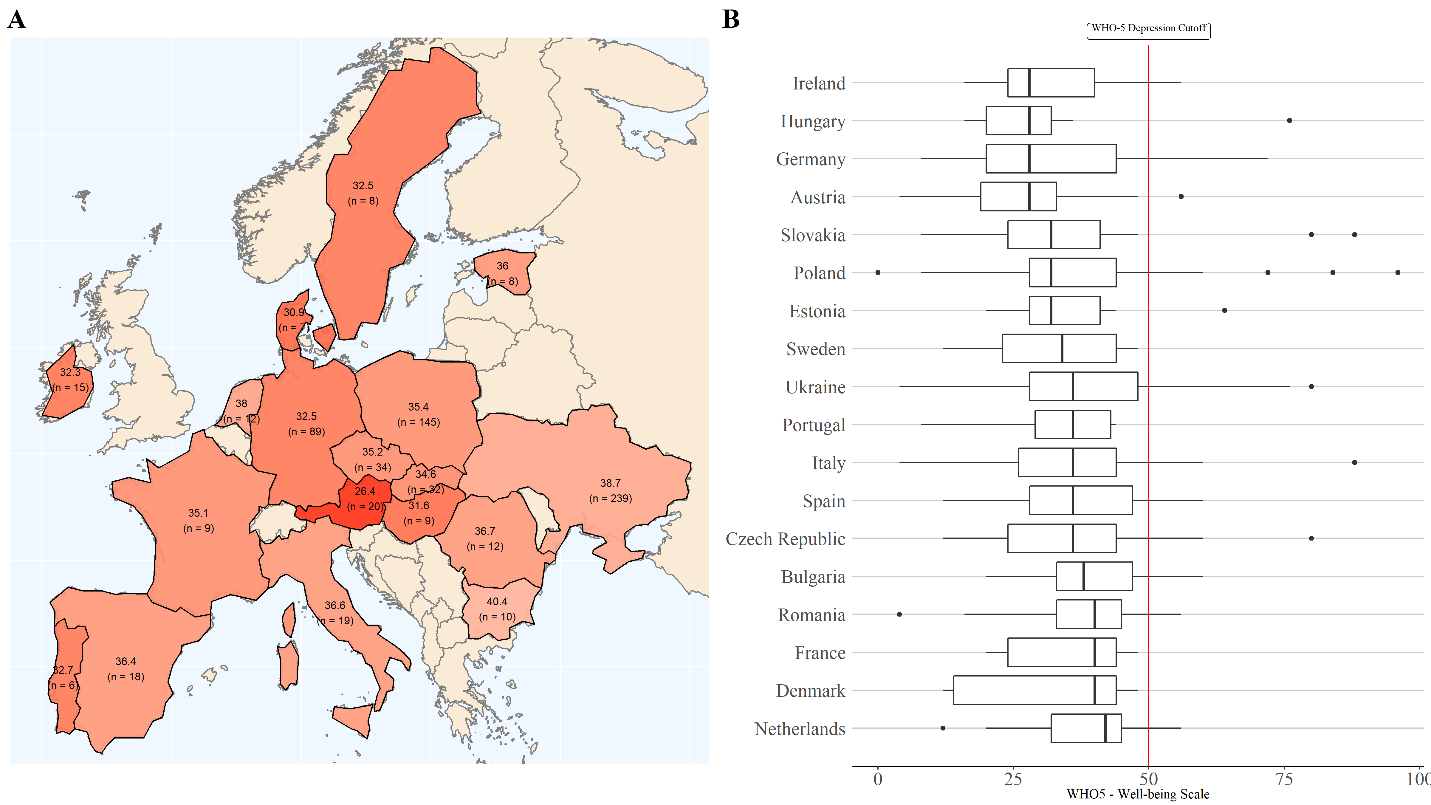

The median refugee or internally displaced Ukrainian seeking help in our sample scores below the “screening depression” cut-off (below 50 points on WHO-5) across all 25 countries covered by the study (see Figure 2). The good news is that Ukrainian help-seekers are reachable online for mental health support, irrespective of location, showing the feasibility of improving mental well-being with online-based interventions.

Online-based interventions can be potentially cost-effective and rapidly scalable. However, they can be less engaging and effective. For example, less than 50% of registered users on massive online courses enter the courseware, only about 20% of participants finish these online courses, and the impact of online mental health programs can be small.

Therefore, there is a risk of rolling out potentially ineffective online programs that can prevent people from seeking other help. Thus, online mental health programs require testing, even if they are based on working offline programs.

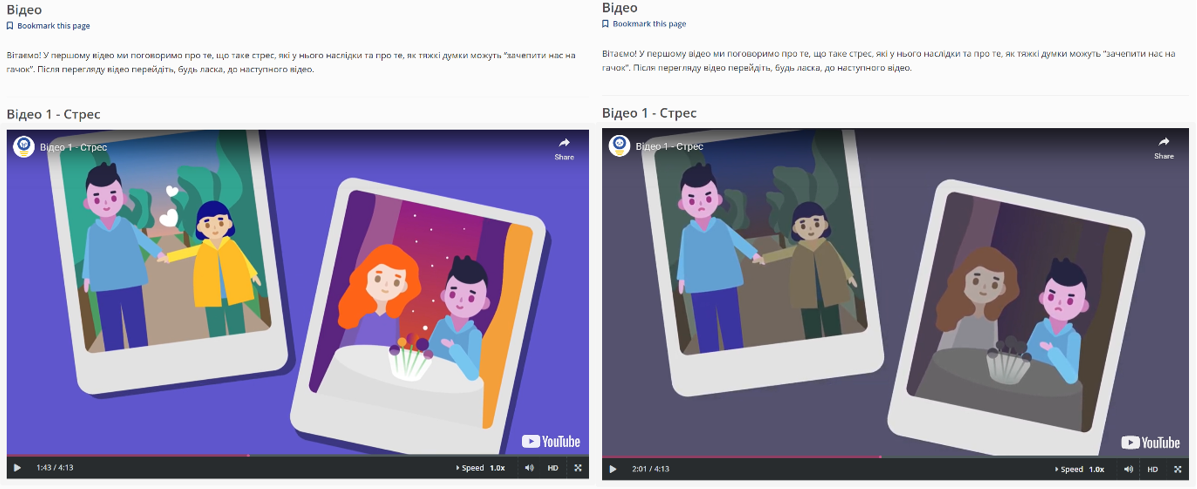

We provided a feasibility assessment and tested a self-administrated individual self-help online course for Ukrainians that aims to improve their psychological well-being and reduce stress. We built the online course in Ukrainian around the WHO Self-Help+ offline materials recommended for online adaptation by the World Health Organization. We adapted these materials to be delivered online using animated videos with a professional narrator who reads the material.

The course is based on acceptance and commitment therapy consisting of five sessions: (1) Grounding; (2) Unhooking; (3) Acting on your values; (4) Being kind; (5) Making room. The course also contains online self-administrated exercises. We complement the course with extensive online information about psychological and other support offered online to Ukrainians in Ukraine and other European countries. We advertised the program over social media during a compressed period of 2 weeks to reduce waiting time.

1165 Ukrainians currently residing across 24 countries of the European Union or in Ukraine registered and agreed to participate in the program and its assessment. To assess the course’s impact on participants’ mental health, the computer randomly chose half of the registered participants to get through the entire program – the treatment group. The rest – the comparison group – received only information materials.

As expected, not everyone who registered decided to participate: slightly more than 50% of registered users entered the platform after registration. Fortunately, among those who entered, the course take-up was relatively high for an online program: 66% of participants studied the first lesson, and 50% finished the last one.

Qualitative feedback from the course participants was also positive. In both groups, mental well-being improved, and stress levels reduced months after the beginning of the program; the impact of the self-administrated individual self-help online course alone remains to be analyzed.

Comments