Many people with chronic conditions or disabilities, particularly those from minoritized ethnic groups, faced obstacles before the pandemic in accessing or utilizing networks of support, health and social care. During the pandemic, some issues increased disproportionately in, and widened the inequalities gap between, people with disabilities from minoritized ethnic groups and those without disabilities and from the indigenous white British population.

It is instructive to consider the interplay of different intersecting factors that compromise good health outcomes when considering inequalities. For example, chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease increase vulnerability to COVID-19 and are disproportionately prevalent in some minoritized ethnic groups. Moreover, such individuals are especially likely to be disadvantaged: almost half of the people living in poverty are disabled or live with someone who is, and poverty rates are highest for people whose head of household is a first-generation Pakistani or Bangladeshi migrant.

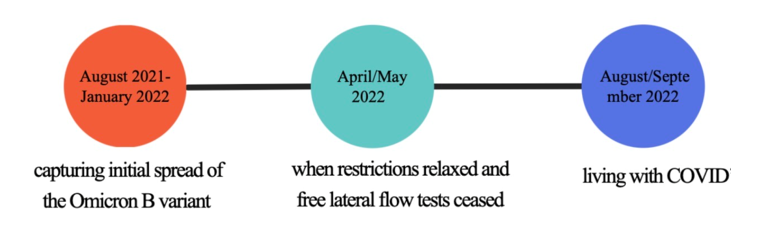

The NIHR-funded CICADA study took an intersectional approach to try to improve the situation for people from minoritized ethnic groups who also have a long-term condition or disability. We aimed to capture the impact of changing pandemic contexts during this longitudinal 18-month study, which started in June 2021.

Our ethos, using an asset- and strengths-based focus, was to learn from and build upon what participants said worked well for them when coping with issues or managing their health, rather than to impose external solutions. We focused on health and social care, informal networks, and access to vital ‘resources’ such as food and medicine and foregrounded the interplay of ethnicity, disability and citizenship status alongside other demographic factors.

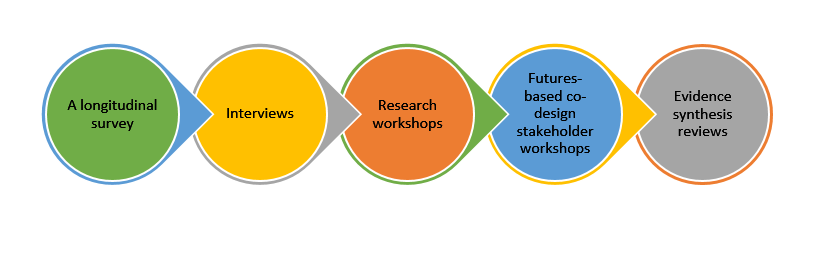

We combined several methods:

- Longitudinal survey: We convenience-sampled 4600 people (careful advertising led to equivalent numbers of indigenous white/minoritized ethnicity, and of disabled/not-disabled), repeating the survey three times:

Key preliminary findings are that:

-

- Social support mitigates the adverse impact of disadvantaged identities (minoritized ethnicity or chronic health condition) on mental wellbeing.

- Different sources of support have different impacts; for example, religious support was only helpful for some groups.

- Respondents could be grouped according to mental health stability and its reactivity to changes in pandemic restrictions; data suggested coping mechanisms were often better developed in those with both chronic conditions and a minoritized ethnic identity.

- Evidence synthesis reviews: We are exploring socially and environmentally constructed barriers for people with chronic conditions/disabilities and barriers to vaccine uptake.

- Interviews: Our 250+ interviews focused on Arabs, Central/East Europeans, Africans and South Asians, to reflect recent migration waves and those at most risk from COVID-19, with indigenous white comparators. Two-thirds were conducted in autumn 2021, mostly at six sites in England (London, Yorkshire, the Northwest, the Northeast, the Southeast and the Midlands) but also including the devolved nations.

Selected findings from preliminary thematic and keyword analyses are:

-

- Racial/ethnic discrimination is reported as more significant in participants’ daily lives than dis/ableism unless their condition has a considerable impact on day-to-day function. However, in some, this may reflect a difference in the way people cope with these different aspects of their identity. Health conditions are embodied experiences that must be managed continually, unlike ethnic identity.

- Higher socio-economic status confers benefits but does not eradicate marginalization.

- Pandemic-related disruptions to and changes in health and social care have decentered participants’ healthcare with deterioration in physical and mental health.

- People with conditions generally perceived as more critical, such as cancer, mostly reported better care. Those with chronic pain and mental health issues mostly reported worse care.

- There is variation in perspectives with locality. Londoners do not necessarily fare better than those in less-resourced rural areas.

- Pride, and concern about being judged a burden, prevented many Central and East Europeans from seeking help.

- Many migrants in poverty paid for private care due to perceptions of cultural inappropriateness within NHS support even when eligible for this.

- Participatory methods:

To extend our reach to undocumented migrants, we involved eight community members as co-researchers; some, with our patient advisory group, worked on core tasks, such as interviewing, analysis and workshop facilitation, throughout the study.

Research workshops with 104 interviewees in May and September 2022 explored changing experiences. In-person and online, these employed co-production tools such as journey mapping and structured brainstorming.

These suggested participants felt vulnerable at the end of the COVID-19 restrictions. The pandemic’s social and financial impact appears to compound inequities, leaving many anxious about the future.

Futures-based co-design stakeholder workshops involving professionals, community leaders, the third sector and members from disadvantaged communities reimagined health and social care interventions and guidance to improve future experiences, health, and wellbeing outcomes. We are developing some ideas into simple, easily adopted but potentially highly impactful resources.

- Outputs with study partners: These include:

- Mental health ‘exercises’ for chronic fatigue

- Workshops for clinicians

- Exploration on embedding some of our recommendations and resources in the routine work of third-sector groups

- Knowledge exchange:

Talks have directly influenced practitioner society and third-sector plans. The PI’s plenary at a European summer school used CICADA as an exemplar for intersectional methods.

We are informing policy locally and via parliamentary channels.

CICADA Stories, performed at the Bloomsbury Theatre, September 2022, was a successful innovative approach to broaden dissemination, with dramatization based on our data, poetry, dance, and Q&A.

In conclusion, using these varied methods, the CICADA study has provided an insight into the experiences of the pandemic and the challenging legacy it has created for many marginalized individuals. It has also created co-designed outputs and recommendations to help support these communities. Our outputs have salience and considerable potential for impact in reducing inequalities in their health and wellbeing outcomes.

This study is funded by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) – Award 132914, and is sponsored by University College London (UCL). Ethics approval has been granted by the Health Research Authority under reference 310741. The study is registered on the International Trial Registry – no. 40370. This study presents independent research commissioned by the NIHR. The views and opinions expressed by authors are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Health Service (NHS), the NIHR, Medical Research Council (MRC), Central Commissioning Facility (CCF), NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC), or the Department of Health and Social Care (UK).

Comments