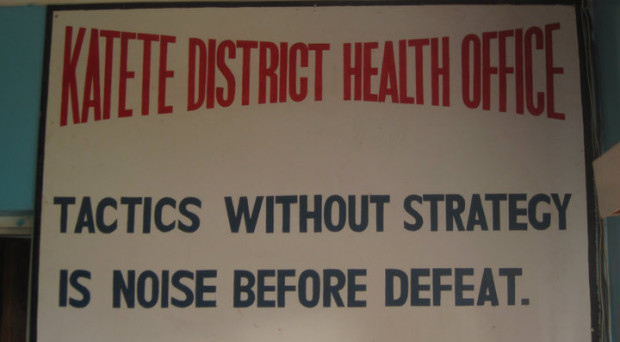

“Tactics without strategy is noise before defeat,” read a large poster featured in the Katete District Health Office (DHO). This motto, explained the office’s director, reflects how Zambia values focused planning and using data to guide health program implementation.

Zambia has a history of using local data to inform the country’s health priorities — and to recognize exceptional performance in providing particular health services. The trophies displayed at Katete’s DHO demonstrate this, including one received for the district’s immunization program.

Our district-level results, as analyzed by researchers at the University of Zambia (UNZA) and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), further highlight Katete’s strong vaccination programming. By 2010, coverage of four key immunizations – BCG, measles, polio, and the pentavalent vaccine – in Katete equaled or exceeded the national average.

But immunization performance represents only part of a district’s health service provision landscape. To help provide a more a comprehensive understanding of Zambia’s health system performance, our team sought to capture a broader range of key maternal and child health interventions than had been previously evaluated.

This systematic approach is critical for examining the delivery of health services throughout a country. You need to know that local variations in service provision reflect actual differences in intervention availability and use rather than local differences in record-keeping and in program-focused investments for monitoring intervention scale-up. In Katete, for example, having a good vaccine tracking system may have contributed to the district’s overall performance but also to its ability to demonstrate success to provincial and national health authorities.

In Zambia, we found a clear divergence in the delivery of disease-specific interventions, namely those for malaria and vaccine-preventable conditions, and routine services that require multiple contacts with the health system. Between 1990 and 2010, coverage of more disease-specific interventions generally increased in equitable ways throughout Zambia. For instance, by 2010, 69 out of 72 districts recorded measles vaccination rates equaling or exceeding 90%, a recommended level of coverage for achieving community-level protection against the disease.

By contrast, the gap between districts with the highest and lowest levels of intervention coverage widened for antenatal care and skilled birth attendance – a warning flag for the provision of routine health services, particularly maternal health services. For example, in 1990, 56 districts showed more than 50% of women receiving at least four antenatal care visits (ANC4) prior to giving birth. Twenty years later, only 22 districts achieved this level of ANC4 coverage.

Increasingly, policymakers and development partners want to know which kinds of policy and investment options will maximize health outcomes and program impact. As calls for more integrated service delivery and universal health coverage (UHC) become stronger, the need for routinely assessing local performance across different interventions and health services grows as well. More frequent and extended benchmarking will help to quickly detect specific challenges facing a country’s health system, such as growing disparities in antenatal care, and point to local examples of successful service delivery, such as Katete’s immunization programs.

We look forward to hearing how these findings will be used in Zambia. We also hope they inspire the demand for subnational benchmarking in other countries and larger investments in local health data monitoring systems. Because at the end of the day, this focus on local health service delivery can only strengthen the evidence base and strategies that districts, counties, states, and so on can use to achieve better health for all of their citizens.

Comments