A new study published today in BMC Medicine has shown that adverse experiences in childhood can have a serious long term impact on both the individual and society. Guest blogger Karen Hughes, Professor of Behavioral Epidemiology at Liverpool John Moores University and co-author on the study, tells us more about their findings.

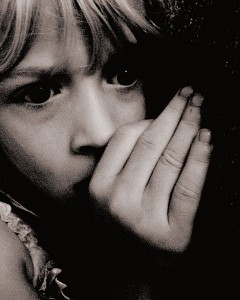

Over the last few decades there has been growing recognition of the impact that early life experiences have on people’s health and behavior. Taken simply, children that are raised in stable, loving environments tend to live healthier and longer lives than those that suffer abuse, family conflict and other childhood stressors.

The mechanisms behind this trend are increasingly being understood; childhood stress impairs healthy social, emotional and academic development. It can cause adaptations in the brain that focus emotional and physical responses towards short term survival rather than long gain.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study in the USA has been instrumental in identifying the health-related impacts of childhood adversity and pushing forward research in this area. By asking patients about their childhood experiences and their health-related behaviors as adults, the study found that the more adverse experiences a person had suffered as a child, the greater their risks of a wide range of health-damaging behaviors and health conditions as adults. These range from substance abuse and risky sexual behavior through to mental ill-health, cancer and premature mortality.

Showing the burden that these childhood experiences place on population health creates a case for governments to invest in effective interventions to prevent them. Thus the World Health Organization and global health partners are promoting research into the extent and impact of them around the world.

Studying the national impact

The aim of our study was to measure the impact that adverse childhood experiences were having on health-related behaviors in England. Most previous studies on these experiences have focused on specific population groups or sub-geographical regions, and few have examined their impact nationally.

In England, there is growing awareness of the importance of early life experiences in setting children’s paths in life and increasing policy focus on early interventions. Yet little is actually known about how many people are affected by adverse experiences in childhood or how they impact on health-related behaviors. We wanted to develop this knowledge and at the same time estimate what impact preventing these experiences might have on the prevalence of health-harming behaviors nationally.

To do this, we conducted a nationally representative household survey of adults across England. We surveyed around 4,000 18-69 year olds using a questionnaire that included a range of questions on past and current health-related behaviors and a short ACE tool developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This measures nine adverse childhood experiences occurring before the age of 18: physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, exposure to domestic violence, parental separation, and living with a household member who has alcohol problems, uses drugs, is mentally ill or is incarcerated.

By adjusting data to the demographics of the national population, we estimated that almost half (47.9%) of adults in England had had at least one adverse experience in childhood, and almost one in ten (9.0%) had had four or more.

We found that, with the exception of low physical exercise, these experiences were strongly related to all the health-harming behaviors we measured. These were: early sexual initiation (before age 16); having or causing an unintended teenage pregnancy (before age 18); eating low levels of fruit and vegetables; smoking; binge drinking; cannabis use; heroin or crack cocaine use; perpetrating violence; being a victim of violence; and being incarcerated.

As with previous work, we found that the prevalence and risk of health-harming behaviors increased with the number of adverse childhood experiences people reported. For example, compared with people who reported none, in those with four or more adverse experiences the odds of smoking increased three-fold and the odds of involvement in violence (whether as a victim or perpetrator) increased seven-fold.

What is the potential impact of reducing adverse childhood experiences?

The really novel part of our study was its estimation of how many people could have been prevented from engaging in health-harming behaviors if they had not had these experiences.

By quantifying the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and the development of health-harming behaviors we estimated the reduction in prevalence of each behavior that would be seen in the absence of these experiences and the numbers of individuals that this equated to across England.

For current levels of smoking, for example, we estimated that with no adverse experiences national prevalence would drop from 22.7% to 18.9%; a 16.5% reduction. In terms of numbers, this would equate to 1.3 million fewer adult smokers across England. For violence, we estimated that prevalence of past-year victimization would drop from 5.8% to 2.9%, a reduction of 50.6% and equivalent to just over a million victims of violence a year.

Our estimates may represent the very upper end of what is possible (i.e. removal of all adverse childhood experiences in a population) yet what they show is just how important preventing these experiences can be in tackling health risk behaviors; and therefore associated chronic health conditions.

By translating our findings into numbers we have turned research into adverse childhood experiences into something that is meaningful to policymakers and practitioners. A range of evidence-based programs are available that can prevent and address experiences such as child maltreatment and domestic violence, and systematic implementation of these programs within nations is likely to have major impacts in improving public health.

Comments