“Isn’t that special?” Many people remember this quip from Saturday Night Live’s TV character “The Church Lady.” Brought to life by comedian Dana Carvey, The Church Lady was as sarcastic as she was smug; her “Superiority Dance” is also legendary. But it was The Church Lady’s signature retort, “Isn’t that special?” that has been immortalized in memes and gifs.

What many people might not know is that disability scholar Simi Linton quotes The Church Lady and her sarcastic retort in an essay curated by the U.S. Disability History Museum as part of its teaching tools. As Linton explains, “terms such as physically challenged, … handicapable, and special … are rarely used by disabled activists and scholars. Although they may be considered well-meaning attempts (by people without disabilities) to inflate the value of people with disabilities,” these terms “can be understood only as a euphemistic formulation, obscuring the reality” that disabled people are not “considered desirable.”

For this reason, Linton references The Church Lady’s iconic retort “Isn’t that special.” Linton argues that The Church Lady’s use of special for phenomena that are “distasteful or morally repugnant” is akin to non-disabled people’s use of special for disability.

Empirical Investigation

In our recent study, we investigated Linton’s and other disability scholars’ assertions. We empirically tested whether the general public has less favorable explicit and implicit attitudes toward the euphemized term special needs than the non-euphemized term disability. Our research participants were drawn from the general population (N=530), and about a third of our participants had a personal relation with disability (as, for example, the parent of a disabled offspring or a co-worker of a disabled colleague).

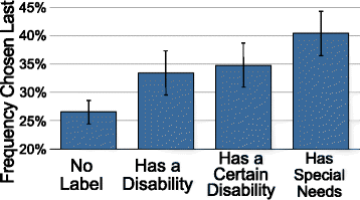

For our implicit measure, we created a set of vignettes that allowed us to measure how children, college students, and middle-age adults are viewed when they are described as having special needs, having a disability, having a certain disability (e.g., is blind, has Down syndrome), or no label at all. We predicted and observed that persons of all ages are viewed more negatively when they are described as having special needs than when they are described as having a disability or having a certain disability.

Because our results demonstrated that being described as having special needs is worse than being described as having a disability (or having a specific disability), we concluded that special needs is an ineffective euphemism. Even for members of the general population who have a personal connection to disability (e.g., as parents of children with disabilities), we found that the euphemism special needs is no more positive than the non-euphemized term disability.

For our explicit measure, we collected participants’ free associations to the terms special needs and disability. We predicted and observed that special needs is associated with more negativity than disability, and special needs evokes more unanswered questions. Even members of the general public who have a personal connection to disability associated more negativity to the euphemized-term special needs than the non-euphemized term disability.

Societal Implication

Our research supports many style guides (and disability scholars) who prescribe not using the euphemism special needs. In addition to its negative connotations, we argued special needs is imprecise; it can refer to groups as unrelated as minority and bi-racial children in the realm of child adoption; middle-age adults and persons without personal transportation in the realm of disaster preparedness; and pregnant women and people with nut allergies in the realm of airline travel).

Special needs also connotes segregation. Most special programs (e.g., Special Olympics and special education) segregate persons with disabilities from persons without disabilities. Special needs also implies special rights. In our research article, we pointed to an OpEd in The Chronicle of Higher Education that misconstrues legally mandated disability rights as special rights, as well as similar misconstruals observed in common vernacular.

We concluded that special needs has become a dysphemism, similar to lame (e.g., a lame idea), crippled, blind (e.g., blind to evidence), and deaf (e.g., deaf to reason). Our research did not explore whether non-disabled people’s use of special needs is intentional (although some instances clearly imply negative intentionality). Perhaps, as Simi Linton suggests, non-disabled people’s ambivalence about disability rather than sharp repulsion underlies their use of the term special needs. Regardless of speakers’ and writers’ motivation, our research recommends not using the euphemism special needs and instead using the non-euphemized term disability.

Comments