In January this year, Fungal Biology and Biotechnology published a work presenting the results of an interdisciplinary artist-in-residence project, which took place in 2021. The artist Sunanda Sharma did her residency in the lab of Vera Meyer and one main result of this work was The Living Color Database. It is about pigments from microorganisms that can synthesize them and how they can be explored by humans. The database itself allows the user to pick a color from a chart and, by analyzing the RGB values of the picked colors, microorganisms (bacteria, fungi and acheae) that are able to produce this or a matched nearby pigment appear. Sharma also linked references for further studies.

At the end of February, I had an appointment with my tattoo artist for a tattoo. While I was lying there, we both talked a little about his work and mine and I also told him about Sharma’s color database. Pigmentation in general is something a tattooist should always be aware of and literally the core element of each tattooist’s work. However, while he was finishing my tattoo, I asked myself if it would be possible to use fungal pigments as tattoo ink? This question is also accelerated by a third event that also took place this year, and all together these inspired me to write this blog article.

In January, the EU put many chemicals used in color tattoo ink under the REACH legislation. REACH is a EU-wide regulation of chemicals and stands for “Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals”. It is a mighty instrument, that helps to make especially new chemicals safer and economically more friendly. However, the message that most color inks are potentially forbidden from now on was shocking for customers and tattoo artists. They are said to be unsafe due to being cancerogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction.

What is (conventional) tattoo ink actually made from?

Tattoo ink not only consists of the pigments, which fall under the regulation. There are also so called carrier ingredients, to ensure even distribution of the pigment while using it and to prevent infection. Most of the pigments are metal salts and some industrial dyes are also used. They also can contain heavy metals.

Usual carriers in traditional tattoo industry are glycerol, propylene glycol, ethanol or listerine. The mineral pigments can vary and depend on the color. Red and brown, for instance, mainly come from iron oxide, whereas green and blue are chromium oxide, malachite or cobalt blue based, respectively. Due to many combinations basically every color can be mixed based on these ingredients.

The demand for alternatives is constantly growing and will grow, considering the EU regulation. Therefore, some alternatives do exist. Most vegan inks are based on organic chemicals, such as Naphthol for the color red, monoazo, a carbon-based pigment substituting green or turmeric for the color yellow, to name some.

Fungal pigments for use as tattoo ink

Coming back to my initial thought, I wondered if it was possible to use pigments described in Sharma’s database as new inks for the tattoo business. Generally speaking, the reasons to do so are very clear:

- Fungal derived pigments are vegan

- Fungi can be cultivated industrially and therefore the process should be economically efficient

- Fungal variety is endless, therefore most colors should be covered

- Fungi can be changed genetically, therefore new colors or combinations could be produced by few species

- Fungi can grow on nearly every substrate, including ligno-cellulosic waste, which is the most abundant feedstock worldwide

- Fungal pigments have been used before in many other processes, such as wool dyeing, painting and writing.

So why has nobody (as far as I know) considered the use of fungal pigments for tattooing? Now we must view this topic from a different perspective

- Safety issues

The use of mineralic pigments is known and practiced for many, many years now. Even some of the oldest preserved bodies in human history, such as the Ötzi or the Chinchorro mummy, had tattoos. Nowadays, our safety requirements are way higher than for the Ötzi. We cannot exclude the possibility that fungal pigments under the skin may cause allergic or inflammatory reaction, if not allergic shock. However, for most of the mineralic pigments that were used before one also cannot exclude these reactions. Different hazards are also associated with classical tattoo ink (https://epub.uni-regensburg.de/47737/1/ddg.14436.pdf).

- Complexity of the pigments

Mineralic pigments consist of different, mostly an-organic molecules simply arranged in a specific grid. Fungal pigments such as melanin are complex, organic molecules coming from specialized metabolic pathways and enzymes. Some people could be frightened off due to this complexity and possible unknown reactions.

- Postprocessing under the skin

It is known that injected tattoo ink is trapped by immune cells, such as macrophages or fibroblasts at the position of injection, making the tattoo permanent. However, it might be possible that this doesn’t work for complex organic pigments, since they could be enzymatically digested, making a fungal pigment tattoo only temporarily visible.

- Regulatory issues

Giving the current situation in the EU which I described above, it seems to be very complicated, if not impossible, to get these tattoo inks approved by local governments. They probably would even not be classified as cosmetic inks, but as other substance classes.

Fungal tattoo ink, a little thought experiment

Ignoring all the disadvantages, I would still like to turn to Sharma’s work and create a hypothetical tattoo for myself using only the pigments described in her database:

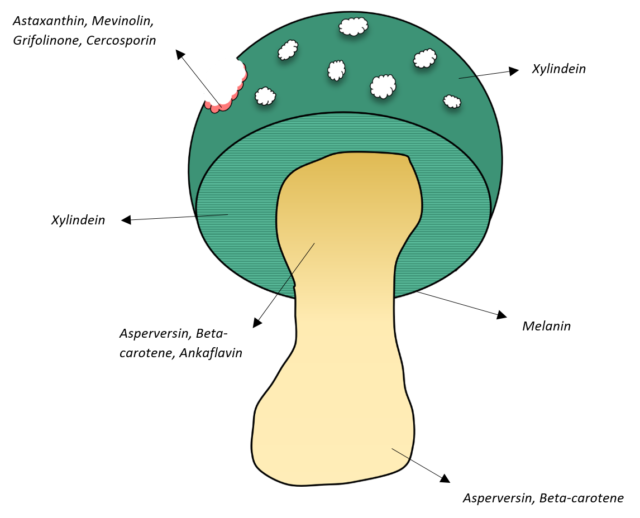

Despite of the green-blue color of the head of my tattoo motive, all other pigments are naturally available by using different fungi. The color-picker of the database is very handy and makes possible to look over quickly and find a proper color, pigment and organism producing this pigment. The following summarizes my hypothetical organisms that I would use to get my mushroom tattoo:

| Table: Some of the matched colors from in detail (Source: www.color.bio/database) | |||

| Color | Matched color name | Organism | HEX Code |

| Blue-Green | Xylindein | Chlorociboria aeruginascenc, C. aeruginosa | #6da1a3 |

| Red | Mevinolin | Monascus ruber, Penicillium citrinum, Phomopsis vexans | #ff0000 |

| Yellow-Orange | Asperversin | Aspergillus versicolor | #ffd75a |

| Black | Melanin | Aspergillus niger, Agaricus bisporus, Aspergillus nidulans | #000000 |

| Pink-Red | Astaxanthin | Yarrowia lipolytica, Pfaffia rhodozyma | #ff9ad2 |

| Golden | Ankaflavin | Monascus purpureus | #e1ab06 |

We will see if using fungal pigments for tattooing will be a new application area for fungal biotechnology. As Sharma describes in her work, the biotech tools not only have the potential to understand phenotypes and fungal biodiversity. They are also useful to enhance the empathy for microorganism themselves, also fungi. This also fits with the idea of a tattoo, as most people are telling an emotional story behind it (although there are also people who tattoo themselves in the rush of other substances without thinking about it). Anyway, an exciting thought and a great contribution by the Sunanda Sharma for scientists, designer, artists or others.

Kustrim Cerimi

Latest posts by Kustrim Cerimi (see all)

- Connecting materials science with fungal biology: A personal insight - 15th June 2022

- Fungal pigments from the perspective of a scientist with passion for tattoos - 25th April 2022

- Fungal metabolites in pre- and postnatal human nutrition: How they may affect us and what to do about it - 25th March 2022

Comments