Diffuse midline glioma is the number one cause of cancer death in children

Pediatric brain tumors are the most common solid tumors in children, with over 5,000 diagnosed each year. For young children with a specific type of tumor that occurs deep inside the brain, known as diffuse midline glioma, there is no effective treatment. Conventional therapy with radiation provides some relief from symptoms, but has no effect on overall survival, with almost all children succumbing to the disease within two years of diagnosis. Despite over forty years of research and novel clinical trials, diffuse midline glioma is uniformly fatal and persists as the number one cause of cancer death in children.

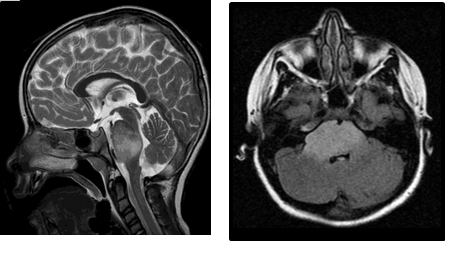

Diffuse midline glioma is particularly difficult to study and treat because it cannot be surgically removed, and diagnostic tissue biopsy is rarely performed. As a result, tumor tissue is not readily available for molecular diagnosis or measuring response to therapy, limiting our understanding of this disease relative to other brain tumor types. MR imaging can be used for diagnosis and to monitor tumor response to treatment, but imaging does not provide information about the molecular biology of a tumor, and treatment effects are often difficult to discern from disease progression, making clinical management even more challenging. Hence there is great clinical need for a feasible method by which tumors arising in these deep brain structures can be better characterized at diagnosis and studied throughout treatment.

Diagnosis of diffuse midline glioma

Histone H3 is mutated in up to 80% of diffuse midline gliomas

Using rare tumor tissue specimens, researchers recently learned that an important protein that controls gene expression, known as histone H3, is mutated in up to 80% of diffuse midline gliomas. These mutations can occur in multiple genes encoding different histone protein isoforms (e.g. histone H3.3 and H3.1), and result in alteration in the amino acid sequence of the N-terminal tail of the affected histone protein (K27M and G34V). These H3 mutations also correlate with distinct tumor molecular characteristics, a more aggressive clinical course, and poorer response to conventional treatment. As a result, detection of a histone H3 mutation in brain tumor tissue through genetic sequencing or histopathologic staining is now considered diagnostic for this disease.

In contrast to midline glioma tumor tissue, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can be easily and safely collected in the clinic, and studied in the laboratory. I previously reported the detection of tumor-related proteins in CSF from patients with diffuse midline and high-grade gliomas. In addition, I also previously demonstrated distinct patterns of gene and protein expression, as well as genomic DNA methylation patterns, in diffuse midline glioma tumor tissue in association with the histone H3 mutation. Because of the high prevalence and biological significance of histone H3 mutation in diffuse midline glioma, and relative ease of clinical CSF collection, detection of circulating tumor-associated DNA (ctDNA) in the CSF could serve as an invaluable tool for tumor diagnostic molecular subtyping at diagnosis and measuring response to treatment. Our group therefore set to determine if tumor-associated DNA could be isolated in CSF from children with brain tumors and sequenced for the presence of histone H3 mutations.

Reporting on the feasibility of detecting histone H3 mutation in CSF

Using a cohort of CSF specimens from children with brain tumors, including high-grade and diffuse midline gliomas, we optimized a DNA purification method for isolating circulating tumor DNA. We found that small amounts of circulating tumor DNA were indeed present in the CSF, and that higher concentrations of DNA were detected when the tumor itself was in anatomical contact with CSF pathways in the brain. We then sequenced this DNA using conventional methods (genomic sequencing of the histone H3 genes), as well as with a novel sequencing approach using molecular primers specific to the histone H3 mutations, custom-designed by our group. Of the six CSF specimens from children with diffuse midline glioma in our cohort, tumor DNA sufficient in quantity and quality for analysis was isolated from five (83%), with the H3.3K27M mutation detected in four (66.7%). In addition, the H3.3G34V mutation was identified in tumor DNA from a patient with supratentorial high-grade glioma. Test sensitivity (87.5%) and specificity (100%) was validated using immunohistochemical staining and genomic sequencing in available matched tumor tissue specimens (n = 8).

“liquid biopsy” in lieu of, or to complement, tissue diagnosis, may prove valuable for targeted therapies and monitoring treatment response

Our results indicate that histone H3 gene mutations are detectable in CSF-derived tumor DNA from children with brain tumors, including diffuse midline glioma. This finding suggests the feasibility of “liquid biopsy” in lieu of, or to complement, tissue diagnosis; which may prove valuable for stratification to targeted therapies and monitoring treatment response. Given these results, our team is now working to collect and analyze patient body fluid samples for RNA, DNA and protein biomarkers. Our goal is to determine whether presence of a tumor, as well as the tumors response to therapy, can be detected by methods that are of low risk to children with diffuse midline and high-grade glioma, to ultimately improve clinical management and treatment outcomes for our patients.

- Pediatric Brain Tumor Mutations are Detectable in Cerebrospinal Fluid - 21st April 2017

Comments