Temperature targets will always be key in discussions on climate change. By determining the ideal limit for a global temperature rise, policy makers can then use that as a starting point for negotiating greenhouse gas emissions limits over the coming decades. While that sounds simple, as many of us know, the reality of climate change negotiations is far from it.

The official target used in the annual climate change discussions known as the Conference of the Parties (COP) is to limit the global average temperature rise to 2⁰C. This is measured from pre-industrial times until 2100, and to put this in context, the world has already warmed by 0.85⁰C since the industrial revolution. But an important question to ask is how this 2⁰C target was originally determined.

It may come as a surprise to some that the 2⁰C target actually originates from early studies in the 1970s. This target then became anchored in policy debates over the decades, and was officially sanctioned as the long-term global goal for greenhouse gas emission reductions at the COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009.

A low temperature target is the best bet to prevent severe, pervasive, and potentially irreversible impacts while allowing ecosystems to adapt naturally, ensuring food production and security, and enabling economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.

Petra Tschakert Pennsylvania State University and IPCC coordinating lead author

Despite support from high and upper middle-income countries with high emissions, the 2⁰C target has been subject to repeated criticism from climate scientists, economists, and political and social scientists.

And over 70% of the parties around the negotiating table, including over 100 low- and middle-income countries and small island states, have repeatedly said that a 2⁰C rise is unsafe for their communities, and insist on a long-term goal to keep global average temperatures below 1.5⁰C. These states include the Pacific nation of Tuvalu that was recently hit by Cyclone Pam.

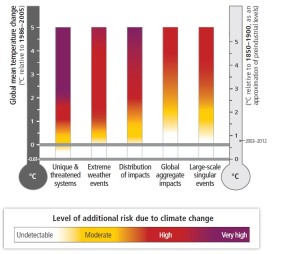

The higher 2⁰C target has been said to carry an increased risk of sea level rise, shifting rainfall patters and extreme weather events such as floods, droughts, and heat waves, particularly targeting the Polar Regions, high mountain areas, and the Tropics.

And yet no reference to an explicit 1.5°C target is included in the 2014 Lima Call for Climate Action, despite specific remarks on the lower temperature limit being made throughout the recent negotiations.

An inside view of climate change discussions

Petra Tschakert from Pennsylvania State University and a coordinating lead author of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report has now presented a rare inside-view of a two-day discussion at the Lima Conference of the Parties in December 2014.

Her commentary in Climate Change Responses summarises the discussions on the average global warming target of 2⁰C versus 1.5⁰C that were part of a ‘structured expert dialogue’ and involved country delegates, IPCC authors and representatives from UN agencies.

Tschakert writes that the consensus that transpired during the session was that a 2°C danger level seemed ‘utterly inadequate’ given the already observed impacts on ecosystems, food, livelihoods, and sustainable development.

She explains: “A low temperature target is the best bet to prevent severe, pervasive, and potentially irreversible impacts while allowing ecosystems to adapt naturally, ensuring food production and security, and enabling economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.”

At the session, a World Health Organization representative stressed that there was no ‘safe limit’ for health, as current impacts and risks from climate change were already unacceptable. These include a rise in undernutrition, food- and water-borne infections, and excess deaths during heat waves, of which 10,000 have already been attributed to the 2010 Russian heat wave.

In addition to heat waves, participants said that extreme events such as floods and hurricanes were expected to be high risk in a 2°C warmer world. These events would threaten disadvantaged populations in megacities like Lagos, Mexico City or Shanghai, people with livelihoods dependent on natural resources, and those at risk from conflicts over scarce resources.

And in terms of ecosystems, limiting warming at 1.5°C could keep sea level rise below 1m, saving half of the world’s corals, and leave some of the Arctic summer ice intact.

Who faces a global average?

Aside from debates on 2⁰C versus 1.5⁰C targets, what also became apparent in the discussions were the huge limitations in discussing or negotiating average global targets.

According to Tschakert, using an average global figure may be the most compelling means to discuss climate change impacts, but not only does it inadequately capture the complexity of the climate system, it poorly reflects locally experienced temperature increases and the extreme variation across regions: “No single person or any species faces a global average.”

Singapore delegates in the discussions highlighted that certain risks were already catastrophic for people and ecosystems in their region while only moderate in the aggregate. Along the same lines, Ethiopia re-emphasized the uneven distribution of risks for the African continent. And Trinidad and St. Lucia stressed regional differences in risk from ice sheet loss and coral bleaching.

Tschakert explains: “These implications emphasize what is truly at stake – not a scientific bickering of what the most appropriate temperature target ought to be, but a commitment to protect the most vulnerable and at risk populations and ecosystems, as well as the willingness to pay for abatement and compensation. This should happen now, and not only when climate change hits the rich world.”

The discussions ahead

Moving to a lower climate change target of 1.5⁰C is without a doubt going to be a massive challenge, when the 2⁰C target is already challenging enough. But raising these points for further discussion is both vital and timely.

The long-term goal to stay below 2°C warming is currently undergoing a 2013-15 Review, the results of which are expected this June and could be adopted in Paris at COP21 in December 2015. And so it becomes more important than ever to reveal the unevenly distributed risks and political power differentials that exist between high- and low-income countries, and increase the chances that a fair compromise can be reached in the negotiations ahead.

One Comment