The Zoological Society of Japan has long published a subscription journal, by the name of Zoological Science. Why is Zoological Letters an important addition to the literature, and what benefits will this sister journal bring?

As a sister journal of Zoological Science, Zoological Letters will cover a wide range of basic fields of zoology, from taxonomy to bioinformatics. Zoological Letters aims to publish more selected original and review articles, approximately 30 papers per annum. In contrast, Zoological Science extensively publishes over 100 papers per year worldwide. Also, Zoological Letters will serve as a pipeline to the database of all animal species published in past issues of Zoological Science.

Why was it important to launch Zoological Letters in a fully Open Access format?

Zoological Letters is 100% open access. This strategy is absolutely essential to the Society’s goal of supporting and fostering basic zoological research in the international zoological community. As the publication platform, it can adapt to the rapidly changing world of academic publishing. It is very important for basic zoological journals, including Zoological Science, to be stabilized at a time when commercial concerns have created competition between journals. This, of course, has had a strong impact on pure scientific research. Zoological Letters is being launched as a new open access journal in the field of zoological research — a stronghold of fundamental science — in response to the requirements of future zoologists all over the world.

Zoological Letters is being launched as a new open access journal in the field of zoological research — a stronghold of fundamental science — in response to the requirements of future zoologists all over the world.

What is your background, and why did you decide to become an Editor-in-Chief, first of Zoological Science and now Zoological Letters?

I was primarily trained in Kyoto University in the field of comparative morphology, mainly focusing upon the skeletal system of vertebrates, especially amniotes. One day, looking at the developing skull of the mouse, I came to an idea that the vertebrate skull is composed of metamerical elements equivalent to the vertebra, almost like the classical ‘Vertebral Theory’ by Goethe. I still remember my mentor was laughing (rather positively) while listening to me. This experience opened up the door to a classical world of comparative morphology and comparative embryology, fields that in Japan had long been dead. So, I obtained my copies of classical textbooks like those written by A. S. Romer or E. S. Goodrich, for example, which I read every day.

When I first obtained a position at Department of Anatomy, University of the Ryukyus, my primary question was still the segmental organization of the head and its evolutionary origin, which continued into my postdoctoral life in USA where I was engaged in experimental embryology of the central and peripheral nervous system. Like skeletal elements, the nervous system also shows segmental patterns in vertebrates. Up to that point, I might have been just one of those dilettantes who tend to turn their back to anything new. But I was always feeling that something developmental and genetic was shared in common between insects and vertebrates.

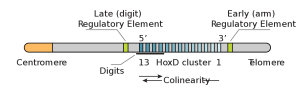

Incidentally, it was around that time that the Hox code was being discovered for the first time, as the genetic machinery to specify segmental anlagen in vertebrate and insect embryos. This was the beginning of what we now call Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Evo-Devo), which later became my specialty. Thus, I witnessed the moment where the classical idea of comparative morphology and molecular-level developmental biology together give birth to a totally new field of research. Simultaneously, I recognized how important it was to blend classical questions and ideas with the most advanced methodology of science. I think that experience was influential when I thought it would be exciting to create a forum where research from all the basic fields, modern or classic, can be mixed together. For this reason, I needed the term ‘Zoology’ as a part of the title of my journal.

What are currently the major challenges in the field of zoological research?

I will not try to define the current mainstream of Zoology today, and again, Zoological Letters welcomes research papers and reviews of all the basic zoological fields. So, I would like to emphasise that everybody should pursue his/her questions, and I want to stimulate research activities in every direction. Yet, the earliest four articles published upon the launch will more or less bias the further submission, I guess, which I think is inevitable. All four papers are rather Evo-Devo oriented, and three of them are obviously on vertebrates. I must stress this journal is not limited to that particular area.

In Zoological Letters also, I think I am going to prefer robust descriptions to problematic experiments, and I want my journal to be an arena where sound hypotheses lead to great discoveries, although I know that this will be very, very difficult.

I am quite interested in basic and evolutionary questions. I am much less interested in applied research of zoology, and I think there are now many other journals specialized for those areas. I would rather preserve the history of traditional zoology on a new scientific background today. So, we will handle papers in all the basic fields evenly. Truly challenging would be to publish exciting and influencing papers of very traditional fields. Fields like comparative morphology or taxonomy, for examples, are not new at all, but they still live and will never end. We can never imagine how new information from these fields will give us hints to solve big questions. In reality, they often provide us with totally new data and ideas with new technologies and ideas classically unavailable. I would like to assist survival of such important fields of zoology to enhance the activity of basic zoology as a whole. I would call that my challenge with Zoological Letters.

To confess, I was very much excited when I first read Peter Holland’s review (the monumental first paper of the journal). In this paper, he summarizes the advancement of recent comparative genomics, especially those of Hox-related homeobox genes, and puts forth a very exciting idea to explain the origin and diversification of metazoan body plans. I believe that this is a splendid method for raising hypotheses, especially since the scenario came up through observations and discussions from multiple angles and multiple dimensions. The story obtained like this makes us open our eyes and say “what if it is true…”. I always think unstable experimental evidence is easily exceeded by sound insights. So, I always tell my students not to jump up to easy experiments, but to think before they move their hands. In Zoological Letters also, I think I am going to prefer robust descriptions to problematic experiments, and I want my journal to be an arena where sound hypotheses lead to great discoveries, although I know that this will be very, very difficult.

Shigeru Kuratani

Latest posts by Shigeru Kuratani (see all)

- Zoological Letters has Launched! A Q&A with the Editor-in-Chief. - 3rd February 2015

Comments