A study published today in Climate Change Responses explains how the El Niño can stunt children’s growth. Heather Danysh, is a doctoral candidate in Epidemiology at the University of Texas School of Public Health and an author of this study. In this guest post, she explains what El Nino is and the affect of climate change on its cyclical nature.

For centuries, the El Niño phenomenon has wreaked havoc on populations around the world through its accompanying extreme weather variability, leading to drought and flood disasters. El Niño-related disasters affect more than four times the number of people affected by other natural disasters worldwide.

El Niño is part of a normal climate phenomenon occurring every 2-7 years, and typically lasts for 9-12 months. An El Niño event is marked by the arrival of unusually warm waters in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of South America. The presence of these warm waters upsets the normal weather patterns in the Pacific Ocean resulting in wetter than usual conditions in Peru as well as other parts of South America, and dryer than usual conditions in other regions such as Australia, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

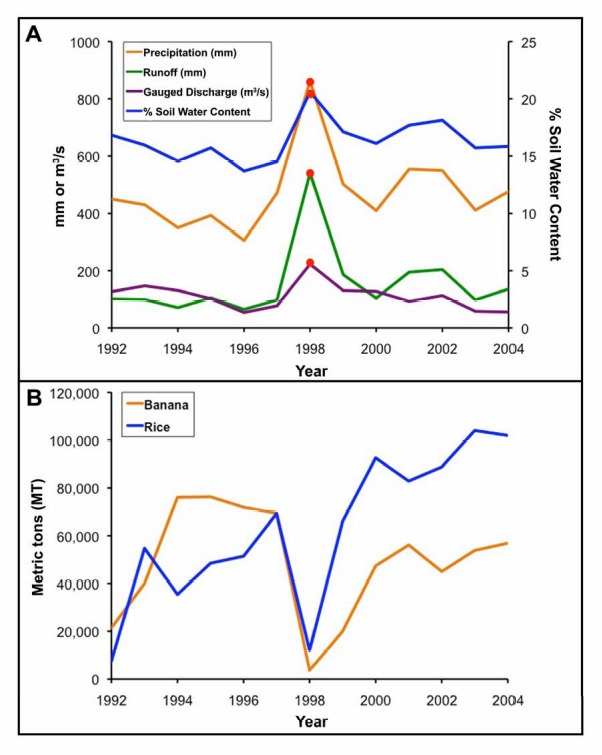

The 1997-98 El Niño event is the most severe on record. During this event, it rained more than 16 times the normal amount of rainfall in Tumbes, a normally arid region located on the northern coast of Peru. The torrential rainfall lead to a flood disaster in this region, leaving many local villages isolated for months by the flood waters as bridges and roads were damaged or destroyed cutting off access to clean water, food, and medical care. Many people lost their livestock and crops, which not only impacted food availability but also affected the economic well-being of these communities.

El Niño events have been blamed for outbreaks of infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, cholera, and diarrhoea, which often occur during or shortly after these events. However, the long-term health impact of El Niño-related disasters is not known.Nutritional status is an important indicator of overall health and well-being. Individuals who do not grow to their optimal height are described as being stunted (i.e., short for their given sex and age), which is an indicator of chronic malnutrition.

Stunting often occurs in early childhood as a result of the inadequate intake of nutrients necessary to grow and develop optimally. Growth faltering in early childhood often stays with the child for the rest of his/her life regardless of improved nutrition in later childhood or adulthood. In other words, it is difficult to “catch up” in growth later on. Stunting has serious implications for later childhood and adulthood including decreased mental and physical capacity and increased risk for chronic degenerative diseases.

To explore the long-term health impact that the 1997-98 El Niño event may have had on a rural population in Tumbes, Peru, my colleagues and I conducted a study in 2008-2009 where we measured and compared the height of children born before, during, and after the 1997-98 El Niño event. Height was measured as height-for-age (HAZ) to take into account the comparisons between different ages and sexes.

We found that, overall, height improves over time in children born in Tumbes before the El Niño event (1991-1997), meaning that children born in later years were less likely to be stunted compared to children born in earlier years. This suggests that overall nutrition was improving in these communities before the 1997-98 El Niño struck. However, children born during and after the 1997-98 El Niño event (1998-2001) had a decreased HAZ, were shorter, than expected. Moreover, children living in homes with the highest probably of flooding had the lowest HAZ. In addition, children born during and after El Niño had lower lean mass for their age and sex compared to children born before El Niño.

Children born during the El Niño disaster and during the aftermath may have lacked a diet adequate for optimal growth and/or may have suffered from infectious diseases due to limited food availability and lack of access to health care, which may be responsible for the decreased HAZ that we observed. Specifically, the lack of available nutrient or energy dense foods, including animal protein, may explain the significantly lower lean mass in children born during and after the disaster.

These findings indicate that the health impact of El Niño is long-lasting, as we detected an association between growth faltering and the El Niño event a decade after the initial disaster. As we write in the article, “Just as rings act as indicators of natural disasters experienced by a tree throughout its life, exposure to severe adverse weather events in utero or early life can leave a long-lasting mark on growth and development in young children.”

El Niño is not only expected to become more frequent in the context of climate change, but extreme El Niño events may also become more frequent. The most extreme weather tends to have most disastrous effects on developing countries such as Peru, with children being the most vulnerable. It is important that we continue to understand the mechanisms behind El Niño and its impact on health outcomes in order to design effective prevention strategies and appropriately target aid and relief during future El Niño episodes.

- Microbial forensics: It’s not just fingerprints that can be left behind - 12th May 2015

- How can ‘conservation genomics’ help the recovery of the most endangered species? - 12th December 2014

- Acetate helps hypoxic cancer cells get fat - 11th December 2014

Comments