What have dogs ever done for us?

Humans and dogs have a long history of co-existence and companionship, and our four-legged friends can have a profound impact on our wellbeing in a number of ways.

The company of dogs has long been thought to reduce anxiety and improve health outcomes, to the extent that Florence Nightingale recommended small pets as “an excellent companion for the sick, for long chronic cases especially” (as Professor James Serpell reports).

Animal-human therapeutic interactions are now an established component of modern medical treatment: the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has had a dedicated team of therapy dogs for cancer patients since 2007. Alongside this, guide and hearing dogs have been able to provide essential support to people who might otherwise be isolated.

Dogs also make a vital contribution to search and rescue efforts. Dr Melissa Hunt and colleagues explored the potential interaction between human wellbeing and canine health and behaviour, in a three year longitudinal study involving rescue dogs and their handlers. Symptoms of depression or PTSD in handlers predicted later behavioural problems in their canine partners, including separation anxiety and aggression towards strangers. The physical wellbeing of the dog was also associated with PTSD or depressive symptoms in its handler.

Valley Water Rescue member, Mike Knorr and search dog, “Barnaby” – image from FEMA Photo Library

All that we share – uniting veterinary and human medicine

While the broad link between our health and that of our canine companions has been established, recent technological advances have afforded us unprecedented knowledge of the biological similarities between our species.

From clinical trials to genetic studies, researchers and clinicians across human and veterinary biomedicine are using what we know about one species to learn more about the other, collaborating in the biomedical areas where dog and human overlap.

This translational approach is already yielding new insights into the genetics underlying the development of eye diseases, anxiety disorders, and cancer in both species. These represent major steps towards improving the health of human and animal patients. With the complete sequencing of the canine genome in 2005 came the public availability of several million SNPs and exciting new opportunities for gene mapping.

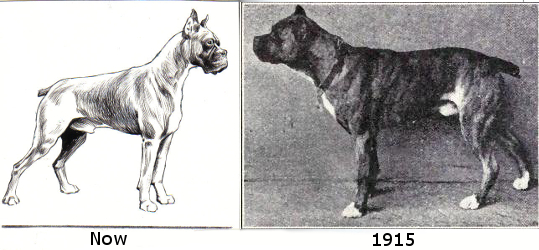

The breeding history of dogs, for specific traits such as long backs and short hind-legs, has resulted in breed-specific susceptibility to specific conditions and diseases. Over-use of sires and studs has exacerbated this lack of genetic diversity in breed populations.

Awareness of overbreeding and its associated health risks is thankfully on the rise, and we can study naturally occurring diseases and disorders in dogs to identify the genes that play a role in their development.

Canine genetics and cancer

Osteosarcoma is a particularly aggressive cancer with near-identical clinical presentation in dogs and humans. Genome-wide association analyses in Rottweiler, greyhound and Irish wolfhound populations identified 33 inherited risk loci for the cancer, where human genomic studies had previously failed to do so.

The next step? Use this genetic information alongside clinical trial data to identify molecular subtypes of the cancer and develop more effective treatments for dogs and humans.

Another recent study took a close look at canine transmissible venereal tumours, which are 11,000 years old and one of only two transmissible tumours in nature persisting today. By looking at the genetic mutations that have helped the tumours to survive for all of these years, we stand to learn more about the mechanisms of tumour growth in both canines and humans.

Genetics of inherited disease

Inherited diseases of the eye have been an especially fruitful area for canine genetics research, especially with respect to identifying genetic mutations associated with retinal degeneration (e.g. X-linked progressive retinal atrophy).

The identification of these mutations has already translated to successful treatment of retinal diseases in dogs. A research team, including Canine Genetics and Epidemiology co-Editor-in-Chief Gustavo Aguirre, was able to restore vision to a blind canine patient. Gene therapy is also being used to treat the equivalent disease – Leber congenital amaurosis – in humans, with promising early results.

Abnormal behaviour

Dogs have been known to behave peculiarly, from looking guilty after misbehaving to defecating in alignment with the Earth’s magnetic field, but abnormal behaviour has become a key area of canine research. There are close clinical similarities between naturally occurring canine compulsive disorder (CCD) and OCD in humans, including symptoms and age of onset.

In a landmark study published last Friday in Genome Biology, Kerstin Lindblad-Toh and colleagues have identified several genes underlying CCD. Genome-wide association of Doberman Pinscher and control dogs implicated four candidate genes (CDH2, CTNNA2, ATXN1, and PGCP) for involvement in the disorder.

These are genes linked to synapse formation and function, and which are functionally linked to OCD-associated SNPs identified in related human studies.

One of the authors of the study, Dr Hyun Ji Noh, explains: “Given how difficult it is to pinpoint genetic causes for complex neuropsychiatric disorders in humans, we thought we could first focus on compulsive disorder in dogs where the gene mapping is relatively easy due to the simpler genetic background within dog breeds.”

The clinical and genetic overlap between CCD and OCD in humans points to abnormal synapse formation as an area for further investigation. It’s another great example of canine and human research converging to reveal new insights into diseases that afflict both species.

Matt Landau is the Journal Development Editor of Canine Genetics and Epidemiology, a new open access journal set to launch in April, published with the support and backing of the UK Kennel Club. You can sign up for article alerts here.

- March biology highlights: octopuses, heavy metal, and pocket-sized DNA sequencing - 10th April 2015

- From farm to plate, make food safe! - 7th April 2015

- Dried up! The effects of 2014 on Western US Lake Ecosystems - 13th November 2014

One Comment