Most mornings, I follow the same ritual: I wake up, take my dog out, have a light breakfast, and settle down with a cup of coffee to read the news. These days, most of the articles are focused on the upcoming US election, but this week, a concerning piece caught my eye, about cases of the mosquito-transmitted eastern equine encephalitis virus in New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

Eastern equine encephalitis, or EEE for short, is relatively rare in the US—the last reported case in Massachusetts happened four years ago, and ten years ago in New Hampshire. It was first recorded in 1831 in the former state, after an outbreak caused 75 horses to die, but it was not isolated until 1933.

Per the presentation linked above, “Since 1964, there have been a reported 270 cases of human EEE, averaging 6 cases per year, which is much smaller than the number of equine cases. The fatality rate is 30 to 70%, which is 1 to 2 human deaths annually, whereas horse mortality rates can be 90% or higher, with death occurring rapidly.” Most of these cases occur during the late summer and early fall, when the mosquito vector, Culiseta melanura, is most active.

The disease causes brain swelling, and symptoms include muscle pain, seizures, and high fever. Horses can be vaccinated for the disease, but for humans, there is neither a vaccine nor a cure. Mortality is about 30%, and those who survive can suffer from brain damage.

In short, it is a very serious disease, and towns in the northeast US are taking it very seriously. According to The Guardian, several public parks have been closed, and towns implemented targeted spraying at night. Others have recommended staying inside during dusk, until the first frost of the season.

Culiseta melanura, the primary vector, don’t feed from humans, or most mammals, for that matter. Instead, their blood meals often come from birds. How then do humans get EEE? That’s where other types of mosquitoes come into the picture. Some, such as those of the Culex or Aedes genera, feed from both birds and mammals and can transfer the diseases after drinking from an infected bird.

Though EEE remains quite rare, there has been an uptick of cases in the past 20 years. Climate change could help explain the increase. Although the range of Culiseta melanura has not necessarily shifted significantly—remember, the first cases in 1831 occurred in Massachusetts—per the Washington Post, “The Northeast has warmed faster than the rest of the country and experienced the biggest increase in mosquito days. In Massachusetts, there have been an average of 14 more mosquito days compared with the period from 1980 to 2009.”

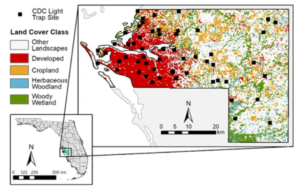

Moving forward, it would be useful to have additional studies on Culiseta melanura, as well as where they coexist with other mosquito species, as the EEE virus typically requires those to move to mammals. A 2020 paper by West et al. looks at how the vectorial capacity of the species changes seasonally. And a 2023 research article by Sallam et al. took a look at the co-occurrence probabilities between mosquito vectors of West Nile and Eastern equine encephalitis viruses in Manatee County in Florida, but further investigations are needed.

In the meantime, if you are in one of the affected areas in the Northeast, it’s important to listen to health officials and take proper precautions, such as wearing mosquito repellents and limiting time spent outside in the evening.

Stay safe!

Comments