At the end of this summer, I’ve gotten some scary, surprising and unexpected news: Aedes aegypti, the yellow fever mosquito has been detected in the town of Talent in Oregon State in the United States. Aedes aegypti is one the most dangerous mosquitoes in the world, capable of transmitting 54 different viruses, including yellow fever, dengue, Zika and chikungunya viruses, as well as two species of Plasmodium parasites. Since the initial detection of a single Aedes aegypti mosquito, an additional 77 specimens of these mosquitoes have been found in 18 traps on northwest Talent. This is surprising because this mosquito has never been found in the State of Oregon, or anywhere in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States before. While this mosquito can be found in the Southern US, the closest locations with documented detections are in Southern California, Nevada or Arizona. Of course, mosquitoes famously have traveled with people to new locations, such as in boats, airplanes, in tires or even in flowerpots. However, accidental introductions don’t always become successful established populations, such as in Talent. This requires the new location to be suitable for the establishment of the introduced species, and this suitability can become more likely over time due to climate change.

Talent, Oregon is a small town of about 7,000 people located in Jackson County, in the southern part of the State, close to California. It has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate, characterized by warm-to-hot and dry summers, with an average temperature of 81.6F. This is the same climate zone characterizing most of the West coast, all the way from southern California to Seattle in Washington State. However, minimum daily temperatures do go dip below freezing during the Winter. Aedes aegypti is an anthropogenic mosquito, meaning it loves to live in association with people, and can breed within homes in small containers, which would protect it from subzero temperatures. While their eggs can survive close to zero temperatures for longer periods, other life stages do require warmer temperatures for survival and development. Aedes aegypti has been documented to have a population in e.g. in Washington D.C., where it overwinters in subterranean environments.

However, climate change might make this area of the United States more hospitable for subtropical and tropical mosquito species such as Aedes aegypti. During the last century, the average temperature in Oregon has increased by 2.2 F, with increasing rates of warming in the last decades. Winters are warmer, extremely cold nights are less frequent, and there are more frequent heatwaves during the summer. There are more days with temperatures exceeding 90F, and due to less snowpack, a higher seasonal risk of seasonal droughts. These changes have benefited the wine industry in Talent, which is a major part of the local economy, with warmer temperatures and longer growing seasons providing improved growing conditions for certain grape varieties. However, these changes have contributed to increasing wildfire risk, demonstrated by the catastrophic Almeda Drive Fire in 2020, which burned down roughly a third of the town. Now, it looks like climate change might have also contributed to the establishment of one of most medically-important mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti, with wine cellars potentially providing overwintering habitat for these mosquitoes.

We have long suspected that climate change might lead to a shift in the geographic range of Aedes aegypti, both globally and in the United States. Using a mechanistic phenology model, Iwamura and their coauthors have predicted that the world became ~1.5% more suitable for Aedes aegypti per decade in the 1950-2000 period, which will accelerate to 3.2-4.4% per decade by 2050. The speed of invasion fronts in both North America and China is projected to accelerate from ~2 to 6 km/year by the same time. A separate study by Kraemer et al., using statistical mapping techniques, have found that by 2050 almost half of the global population will be at risk of pathogens transmitted by this mosquito.

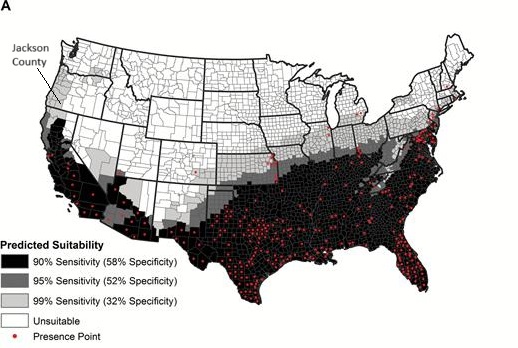

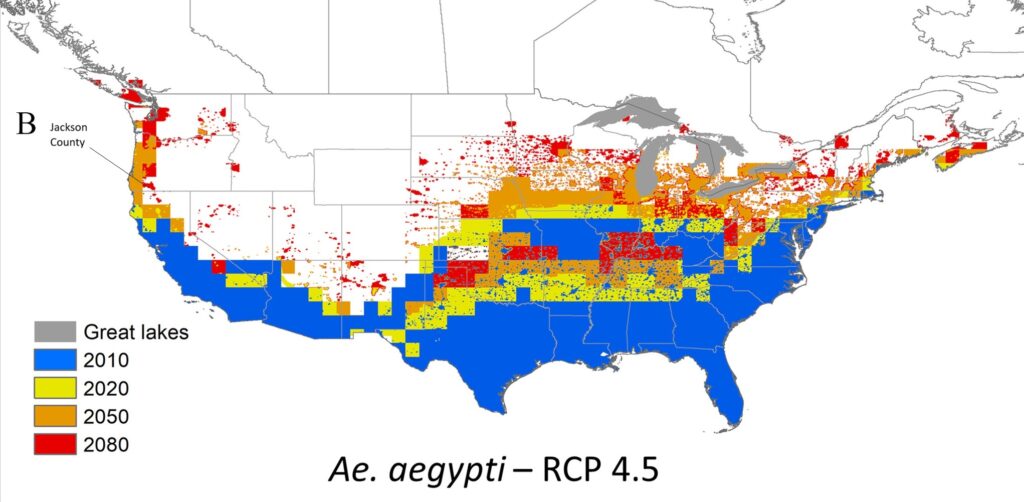

In the United States, the Center for Disease Control also updated their projected estimated range maps for both Aedes aegypti (and its closely related relative Aedes albopictus). This update was based on a study conducted by Johnson et al. that used MaxEnt to model the niche of these two mosquito species based on historical records and climate variables in the 1980-2015 period, finding winter temperatures to be the most important predictors. However, Jackson County, in which Talent is located, is only in the “unlikely” category in the CDC maps, which corresponds to counties predicted to have Aedes aegypti with only 99% sensitivity (true positive rate) and 32% specificity (true negative rate). Given that winter temperatures are expected to increase with climate change, this might expand the projected range of this mosquito. A further study by Kahn and coauthors used a machine learning technique, boosted regression trees, to predict Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus distributions based on current and projected climate and land cover, and found that by 2100, much of the United States and Canada will be suitable for both species. However, they still predicted Jackson county and the Pacific Northwest to only become suitable by 2050 or 2080 at the earliest.

Based on these projections, what does the discovery of Aedes aegypti in Jackson County, OR mean? Does it mean that the above models underestimate the speed at which the range of this mosquito shifts? I would argue that is not necessarily the case. While some models can be functionally correct, unexpected events can completely invalidate the projections of the model. It’s possible that the current detection is just an errant batch of mosquitoes who got accidentally transported to Talent and have spread a bit in the town during the summer, but the combination of cold winter temperature and mosquito control will be sufficient to eradicate them, at least for now. However, the habits and biology of this mosquito doesn’t lend itself to easy eradication. They can lay their eggs and breed in a quarter of an inch of water in a tiny container such as a bottlecap, and their eggs can survive desiccation for over a year.

The Jackson County Vector Control District has attempted to control these mosquitoes with integrated pest management (IPM), including education, surveillance, source reduction and adulticide spraying. While IPM, especially community-focused source reduction can be highly effective at controlling mosquitoes, it can be challenging to get started and to maintain it, since it relies on behavioral change of the community. Given the hardiness of diapausing eggs of Aedes aegypti, a couple of missed containers can later become a source of the reinfestation of the community, requiring another round of source reduction. While this makes me skeptical about the prospects of local elimination, I applaud the dedication of the community and the staff of the Jackson County Vector Control District in trying to deal with the situation. We certainly don’t want the mosquito to use the town of Talent as a springboard to reach other, similar locations, where it can also establish. Honestly, I have never considered that I might have to deal with Aedes aegypti for example in my local collections here in Spokane County, Washington State. However, maybe I should start watching out for them!

Comments